The broad policy priorities identified are expected to strengthen job creation

South Africa has come a long way since the advent of democracy but its transition remains incomplete. The first three clauses of the Freedom Charter, the 1955 document setting out the central objectives of the democratic movement, were: the people will govern; all national groups will have equal rights; and all people will share in the country’s wealth.

The first two objectives have largely been achieved since the first democratic elections of 1994 but historical disadvantage remains a determinant of income, wealth and opportunity.

Poverty has declined significantly since 1994 but inequality remains high. Improved access to basic services such as electricity, water and sanitation, the state provision of more than four million houses and the expansion of the social wage have considerably improved living standards for millions of South Africans.

A progressive fiscal system, expanded access to credit, jobs in the private and public sectors and affirmative action policies have reduced inequality between black and white South Africans, although inequality within the black population has increased. Overall, inequality has risen since 1994 and, in some cases, government policies have inadvertently helped to entrench it further. According to World Bank Group data, South Africa remains the world’s most unequal country.

Creating jobs, especially for young people, is critical to overcome the legacy of exclusion. Jobs are also important to build a stronger social contract. Large-scale job creation reduces economic vulnerability and helps to transform the economy to become more representative of the population. But only about 60% of working-age South Africans participate in the labour force and unemployment is high (27%), especially among young people (more than 50%).

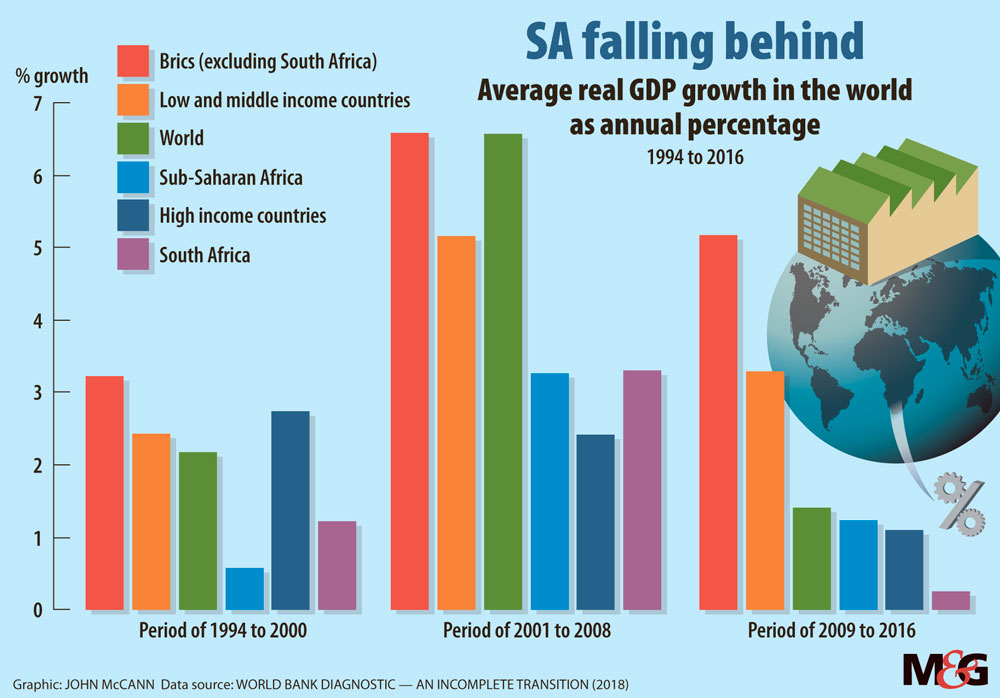

To create more jobs, the economy needs to grow much faster than it has since 1994. But the legacy of exclusion in land, labour, capital and product markets hampers growth. At the same time, high inequality and the legacy of exclusion fuel the contestation over resources, increasing policy uncertainty and deterring investment, while also undermining the financial stability of state-owned enterprises and their ability to provide quality public services. This, too, has weighed on growth.

The World Bank Group’s twin goals are to help countries to eliminate poverty by 2030 and boost shared prosperity. These goals are also enshrined in South Africa’s Vision 2030 in the National Development Plan. The World Bank Group is preparing for its 2019-2022 Country Partnership Framework with South Africa and has drafted this systematic country diagnostic (SCD) to strengthen its understanding of key constraints to achieving these goals.

The broad policy priorities identified are expected to strengthen job creation, and reduce poverty and inequality. These resonate with contemporary calls for an “economic Codesa” — a reference to the Congress for a Democratic South Africa negotiations in the early 1990s, which led to the political transition from apartheid.

Overcoming the legacy of exclusion requires a stronger social contract, and in the February 2018 State of the Nation address, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced that a new social compact would be negotiated in collaboration with business, labour and civil society. This is an essential foundation on which to build the country’s future and the private sector will have to play a more active role in shaping policy and creating jobs.

This SCD identifies five key constraints: insufficient skills; the skewed distribution of land and productive assets, and weak property rights; low competition and low integration in global and regional value chains; limited or expensive spatial connectivity and under-serviced historically disadvantaged settlements; and climate shocks, which include water insecurity and a transition to a low-carbon economy.

Insufficient skills is the key constraint to reducing poverty and inequality. Skills are critical for both labour supply and demand. They raise the productivity of workers and entrepreneurs, help firms to expand production at competitive prices, lead to additional hiring, boost aggregate demand, and contribute to a growing economy.

But South Africa’s learning outcomes are still poor by global and regional standards because of the legacy of “Bantu education”.

Inequality is also reflected by low household savings and high levels of indebtedness. Vision 2030 stresses that improving the quality of education is an essential ingredient for national development.

The highly skewed distribution of land and productive assets is a source of inequality and social fragility, fuelling contestation over resources. Property rights are weak or under pressure. Despite some progress, wealth and land ownership remain highly concentrated. Public housing programmes provide a growing number of poor households with tangible assets. But a lack of title deeds to property, especially in poor and informal areas, limits its value, including as collateral to access finance. Security of tenure in the former homelands is also tenuous.

As a result, even where the poor hold land, its value is limited. Calls for land expropriation without compensation and aspects of the third Mining Charter fuel concern about property rights. A new social compact will require greater certainty about what will be redistributed and how this will take place while ensuring that secure property rights provide a sustainable platform for investment.

Property rights are critical for all South Africans to use their assets to support economic growth, household incomes and jobs. Black economic empowerment should be evaluated to ensure that it becomes truly broad-based while minimising adverse effects on investment.

Low levels of competition and integration into global and regional value chains deter growth and job creation. They also keep prices high, especially for the poor. The country’s banks are well integrated into the global economy but manufacturers have traditionally been protected by natural trade barriers (for example, distance) and a history of import substitution and industrial policy support.

The country’s product markets have high barriers to entry and are poorly integrated with the global economy. As a result, businesses miss out on opportunities to trade internationally and grow through technology transfers associated with participating in the value chain.

This is especially a problem for smaller firms, which struggle to find new demand in a stagnant economy and face barriers imposed by incumbents.

The skills constraint exacerbates matters, particularly hurting manufacturers, small companies and emerging entrepreneurs and farmers. Productivity gains from competition and innovation are needed to produce goods more cheaply for all South Africans, especially the poor, allowing their budgets to stretch further.

Enabling business to compete effectively will have the dual benefits of overcoming the exclusion of historically disadvantaged South Africans and ending the country’s historical isolation from global markets.

Exclusion is also underpinned by limited or expensive connectivity, and underserviced historically disadvantaged settlements. Many South Africans continue to live far from job opportunities in underserved townships, informal settlements and the former homelands. This makes commuting expensive.

There has been significant migration from rural to urban areas as people seek work. Although migration reduces poverty, it can also put pressure on public services and raise social tensions as new arrivals compete with existing residents for jobs, services and business.

The government has made considerable efforts to reduce these skewed spatial patterns but has at times inadvertently reinforced them, for example, by adopting housing policies that do not encourage urban densification. Urban planning is increasingly focused on sustainably densifying cities but this is a long-term process.

For some years to come, many South Africans will continue to live in relatively remote locations with limited employment opportunities. Access to electricity, water, sanitation, good public clinics and schools, and financial services remains much weaker in such areas, limiting opportunities for growth and weighing down living standards.

Improving internet connectivity and low-cost broadband access can help to increase connectedness.

Climate change will impose considerable costs on South Africa, which relies heavily on coal to power its economy. Managing the low-carbon transition and addressing water insecurity will be critical. Cheap coal was one of the key factors in the country’s development, and the economy remains heavily dependent on coal for energy and mining.

In the transition to a low-carbon economy, a viable decarbonisation strategy will be needed to ensure that important economic sectors are not negatively affected. This includes implementing the carbon tax and accessing private investment for energy conservation and clean energy technologies.

Although climate change will exacerbate the country’s water problems, it is not the reason for the structural water deficit. Population growth, urbanisation and economic expansion are increasing demand for water, outstripping fixed supply. Addressing this deficit requires policies targeting water supply, management and demand.

Climate-smart agriculture will be important to guarantee adequate food production for South Africa and the region and to protect farmers’ livelihoods, as will insurance products covering climate shocks.

Public institutions have served South Africa well. Their integrity needs to be upheld and strengthened. The country has a vibrant democratic system, a capable civil service and a strong and independent judiciary and central bank, as well as robust media. Corruption, or “state capture”, has been undermining the quality of institutions, especially the state-owned entities, since 2009.

A renewed emphasis on transparency, strong procurement systems and accountability (on the boards of state-owned entities and others) are needed to ensure effective service delivery.

Improvements in education will enable citizens to hold government more accountable. Institutions can also be strengthened by improving policy co-ordination, monitoring and evaluation. A leaner civil service focused on priorities, coupled with the consolidation of state departments, can improve the implementation of policy and will reduce competition for skilled workers and entrepreneurs with the private sector.

The global economic recovery, coupled with renewed commitment by South Africa’s political leadership to strengthen institutions and strengthen the social contract, presents an enormous opportunity. But social progress takes time. Managing expectations will ensure that disappointment does not undermine South Africa’s continued progress toward its Vision 2030.

This SCD, based on both new and existing research, was developed byextensive consultation with South African organisations and individuals. But knowledge gaps remain. Future areas of interest for the World Bank Group team include interventions in basic education that can raise learning outcomes for the poor; improving the affordability of tertiary education in collaboration with the private sector; developing township and rural economies; exploring how small firms can support growth and job creation; sustainably enhancing national water resources; preparing workers and communities for the low-carbon transition; harnessing the potential of natural resources to benefit historically disadvantaged communities; and encouraging greater foreign direct investment.

This is an edited version of the World Bank Group’s executive summary of its book, An Incomplete Transition: Overcoming the Legacy of Exclusion in South Africa