Sitting pretty: Steve Komphela

Squares of red and white tape wrapped around four wooden pegs dot the once-vacant field between Parkwood and the M5 highway in Cape Town. Men and women carrying spades, hammers and rope walk across the sandy field dug with trenches. Every 10m another fire is being stoked for warmth; some are preparing tonight’s meal in cast-iron pots.

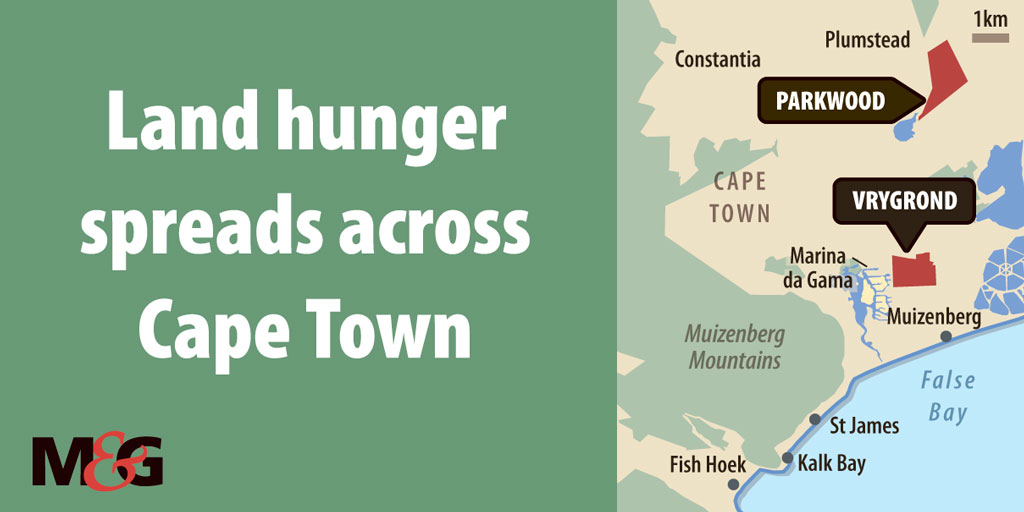

“What’s good for one is good for all. They did it in Hermanus and they did it in Vrygrond. Why can’t we do the same here in Parkwood?” George Casper asks, standing next to his squared-off plot of land.

It’s his fifth day on the patch of land he occupied illegally in Parkwood, a neighbourhood of about 20 000 people living in blocks of flats, semi-detached homes and houses, behind which backyard shacks, each housing two or more families, are packed.

Parkwood is squeezed between Grassy Park and the highway. It has an unemployment rate of about 50% and 43% of the residents own their homes, according to the 2011 census.

Casper has already survived rubber bullets, teargas and a full day of protests in defence of his claim.

“The thing is, if we leave here, we won’t have any hope of getting land. We, as a community, now have hope that we can get this land, and I must fight for that hope. And you fight through staying here. Through not moving,” Casper says.

The occupation followed a protest over poor living conditions for people who live in shacks in backyards, which saw Parkwood residents blocking the highway and facing off with police.

When the local councillor did not agree to build more houses, Dominique Booysen joined religious and sports leaders in calling for a land occupation last Friday.

“The community wanted to know when they were going to get houses. But they weren’t getting answers, so they decided to occupy the land until they get those houses. And because I am on the ground among the people, I am also the person that tries to control the community and make sure there’s peace, so they asked me to help co-ordinate,” Booysen says.

The number of illegal land occupations has spread across the Western Cape this year, with protests in Hermanus, Masiphumelele near Noordhoek, Vrygrond near Muizenberg, and Parkwood.

[Many remain resolute after the removals, and said they would rebuild — and stay put. (David Harrison/M&G)]

Demonstrations in Hermanus saw 21 people being arrested in March, and in Parkwood at least 25 people were arrested this week. Casper says this was part of the struggle to be heard by the government, and was necessary to get results.

This month Casper marks 22 years as a Parkwood resident, and he says he has been on the housing waiting list that entire time. Last year, people who were on the waiting list in 1993 were moved to Pelican Park near Grassy Park, reigniting Casper’s hope that he might receive a house soon.

He decided to take land in Parkwood as a symbolic action to spur the government into action and speed up his application, he says.

“To be honest, I know I probably won’t get this land that I’m standing on. This is a wetland. I can’t dig a foundation here. But this protest, right next to the highway, it will make the right people listen and can lead to something real,” Casper says.

Democratic Alliance Western Cape leader and human settlements MEC Bonginkosi Madikizela visited Parkwood on Tuesday and committed to addressing the residents’ “genuine concerns” and speeding up delivery to people on the waiting list.

But he left the area without telling residents whether he would award them the piece of land they had been occupying or whether they should vacate it.

Returning to their backyard shacks is a grim reality that many people on the occupied field are struggling to accept, Booysen says. With hardly any space to move between the

two or three shacks erected in any given yard, and a lack of privacy between adults and children, disagreements are rife and sanitation is neglected.

“The people are going to refuse to go back to the backyards. They don’t have anywhere else to go. I think going back is their last option,” he says.

Although blocks of freshly painted flats dominate the entrance to the suburb, residents say the dilapidated buildings behind them and the overcrowded yards tell the true story of the impoverished area.

“I can’t even put a washing line in my yard, the way there’s no space. The one lady is living in a shack where the sewage is running past her front door, and she can’t even move because there’s two shacks next to her,” Parkwood resident Hillary Swarts says.

“It’s about privacy, man,” another man building a shack interrupts. “I also want to be able to lock the door to my own place and come back and open it again and know nobody has touched my stuff,” he says.

The desperation for land from people living in backyard shacks was revealed by the numbers who rushed to stake their claim on the field this week. Among those marking off their plots of land are grandmothers in their kitchen aprons and young, unemployed men and

women.

The ground is sandy and loose but the prospective land owners don’t mind because, as Swarts says, “anything is better than where we are”.

A narrow, tarred pathway separates one side of the field from the other, and is used every morning by Parkwood residents walking towards the main road to catch taxis. But the route, which once crossed vacant land, became treacherous because gangsters would lie in wait behind the ridges before dawn and rob passers-by.

“When the people who went to work on Monday came past here, they said it’s right what we [the land occupiers] are doing because they used to get robbed. They came to say thank you, we are making the pathway safe,” Swarts says.

She and her peers are proud of their land occupation and will fight to defend it, she says. Along with the women living in backyard shacks, Swarts has been at the forefront of the occupation in Parkwood.

On Tuesday morning, these women were among the first to rebuild their structures, which had been torn down by the police. That night, they organised a soup kitchen to feed more than 200 people.

“We are doing it for our children. There’s five or six people in a shack and really, we need more space. It can’t go on like this any more,” says another Parkwood resident, Sarah Stuart.

Church and mosque congregations and businesspeople have contributed to their cause.

On Wednesday, the women were the first line of defence against the metro police sent to destroy the temporary structures and clear the field.

“When the metro police arrived with their shields, the women were forming a human chain to stop them from going on to the field and destroying the structures,” Booysen says.

He tried to stop them destroying the shacks but failed. “I said to the person in charge: ‘Let’s go talk to them peacefully,’ and he said they are not here to talk; they came to remove us by force,” Booysen says.

The police arrived clad in riot gear, gripping shotguns aimed at men and women hiding behind their temporary wooden and plastic structures. Moving down the adjacent street shielded by a water cannon, the metro officers ran in groups of four, firing a volley of rubber bullets at the scattering crowds and retrieving burning tyres on the road.

“The other community members made a chain; they ran over them with the shields. Women were dragged, children were injured. That’s when I got shot in the face,” Booysen says.

But as night falls on Parkwood and the materials used to build the shacks have been cleared by police, Casper neatly packs away the supplies he managed to salvage.

“I just want to make sure it’s not damaged so I can put down these markers again and rebuild my shack quickly in the morning,” he says. “It’s the only way they will listen.”