A cancer patient receives treatment.

Only one radiation oncologist is left to treat cancer patients in North West, a health department statement shows.

“With only one oncologist, cancer treatment here is impossible,” says Adele Botha, the North West divisional manager for the Cancer Association of South Africa (Cansa).

South Africans have a 19% chance of developing cancer before they turn 75, according to 2012 data from the World Health Organisation’s International Agency for Research on Cancer. Figures like these mean the sole specialist, who works at the Klerksdorp Tshepong Hospital Complex, could be left to treat more than 660 000 patients.

Cancer patients don’t have time to waste, but Botha says staff shortages and treatment backlogs are forcing people in North West to go without treatment entirely.

She explains: “When people get to the oncologist in Klerksdorp, they aren’t seen immediately. After sitting in a queue for two days, they usually go home until they have the energy to queue again.”

One of Botha’s cancer patients has been struggling to get treatment in the public sector since 2013.

In April, photos of Ntombizodwa Matthews being transported home from Mafikeng Provincial Hospital went viral. She had been sent home as protests calling for then-premier Supra Mahumapelo’s resignation had encircled the facility, forcing health workers to discharge patients.

Matthews had been diagnosed with breast cancer, but her family says she was never told. She died a month later without ever seeing a specialist or receiving treatment despite the fact she had reported the lump in her breast to health workers almost a year ago.

The Matthews family were forced to watch as their loved one became collateral damage in the collapse of North West’s health services. (Oupa Nkosi)

The Matthews family were forced to watch as their loved one became collateral damage in the collapse of North West’s health services. (Oupa Nkosi)

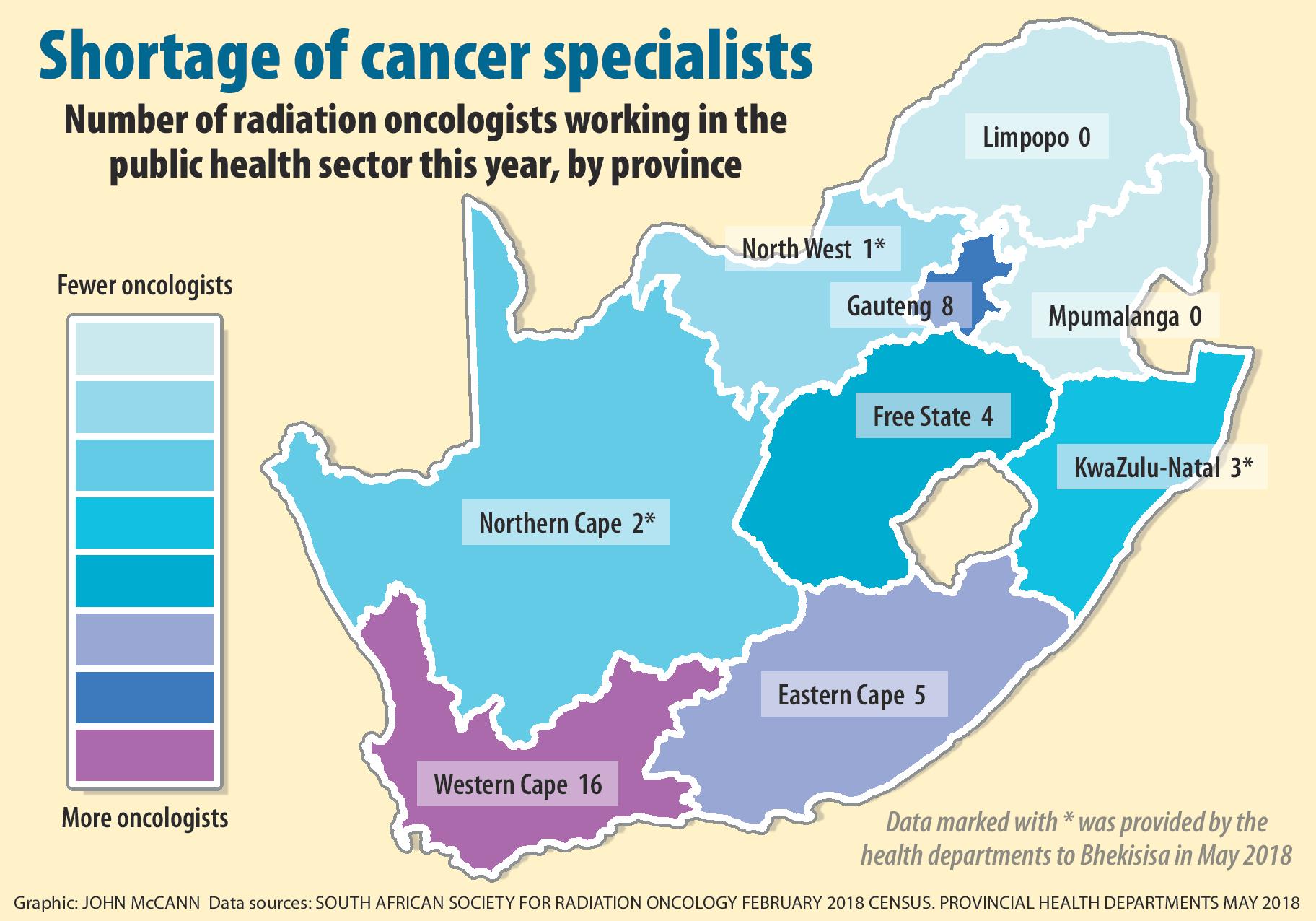

North West is not the only province struggling to care for cancer patients. Only 38 radiation oncologists are working in public hospitals across the country this year, annual census data from the South African Society of Clinical and Radiation Oncology (Sascro) shows. According to the census, not a single radiation oncologist remains in Limpopo or Mpumalanga.

Meanwhile, experts fear North West’s crisis in oncology care is a symptom of a province’s ailing healthcare services — with no cure in sight.

“It’s not only in oncology. There is a total breakdown of health services in the North West,” says oncology social work manager and cancer advocate Linda Greeff.

The first thing that happens when a system collapses is that doctors see fewer new patients, Greeff says. Diagnosing cancers may also become more difficult. As surgery backlogs grow, biopsy procedures to determine whether someone has cancer are also likely to be delayed.

“When cancer treatment relies on only one doctor, the whole system suffers. Not only is it more expensive to treat patients with advanced cancer, but the patient is less likely to survive,” explains Cansa head of health Michael Herbst.

KwaZulu-Natal’s cancer care crisis paints a dark picture of what might already be happening in North West and other underserved provinces, Herbst says. The last public sector oncologist in Durban left in June 2017, leaving just three public sector specialists at Grey’s Hospital in Pietermaritzburg.

[WATCH]: How KwaZulu-Natal’s cancer services collapsed.

[multimedia source=”http://bhekisisa.org/multimedia/2017-09-08-watch-cancer-care-crisis-in-kwazulu-natal”]

The province has since roped in private cancer specialists to treat patients, but people are still forced to wait up to a year for an appointment with an oncologist, data presented at a recent South African Human Rights Commission hearing showed.

And without a radiation oncologist, even existing patients have little hope of getting treatment. Only a radiation oncologist can decide whether a patient needs to have surgery, chemotherapy or radiation treatment and whether the treatment is working, Greeff says.

“Without their recommendation, there is no further treatment.”

Greeff argues that bad budgeting could be behind North West’s cancer treatment woes: “Money for cancer treatment should be controlled by the national health department. At the moment, provinces control their [own] budgets, but the money often disappears, and so do the cancer services.”

When provinces control the budgets, the national department is completely powerless over what happens to the money, she says.

The nongovernmental organisation Rural Health Advocacy Project (RHAP) works to help health districts to analyse budgets. In North West, the advocacy project found that budgets allocated to specific line items, such as human resources, are often underspent and instead reallocated to provincial priorities or goods and services budgets that are used to procure services and buy medicines.

In the goods and services budget, there is greater opportunity for directing the funds to service providers such as the Gupta-linked medical technology company Mediosa, which illegally won an R180-million tender for two mobile clinics in the North West, RHAP’s health system and policy programme manager Russell Rensburg told Bhekisisa in April.

Now, even in well-resourced provinces, nonprofit organisations are being forced to pick up the government’s slack. Cape Town-based breast cancer treatment programme Project Flamingo performs surgery for breast cancer patients in a bid to slash backlogs.

“These doctors are working for free to provide a service that a working health system could easily cover.”

The Western Cape is the province with the most cancer specialists. Sascro’s data shows 16 radiation oncologists worked in the province’s public sector this year.

In North West, Burger and her team at Cansa will continue to screen as many North West patients for cancer as they can. But she fears they will get stuck in the province’s underresourced clinics and hospitals.

“We work very hard to get people screened for cancer. We then send them to clinics and hospitals. And they just get stuck there. And they won’t get treated, or even diagnosed in time,” Burger says.

“They’ll get stuck there in the queue, and just become a number.”