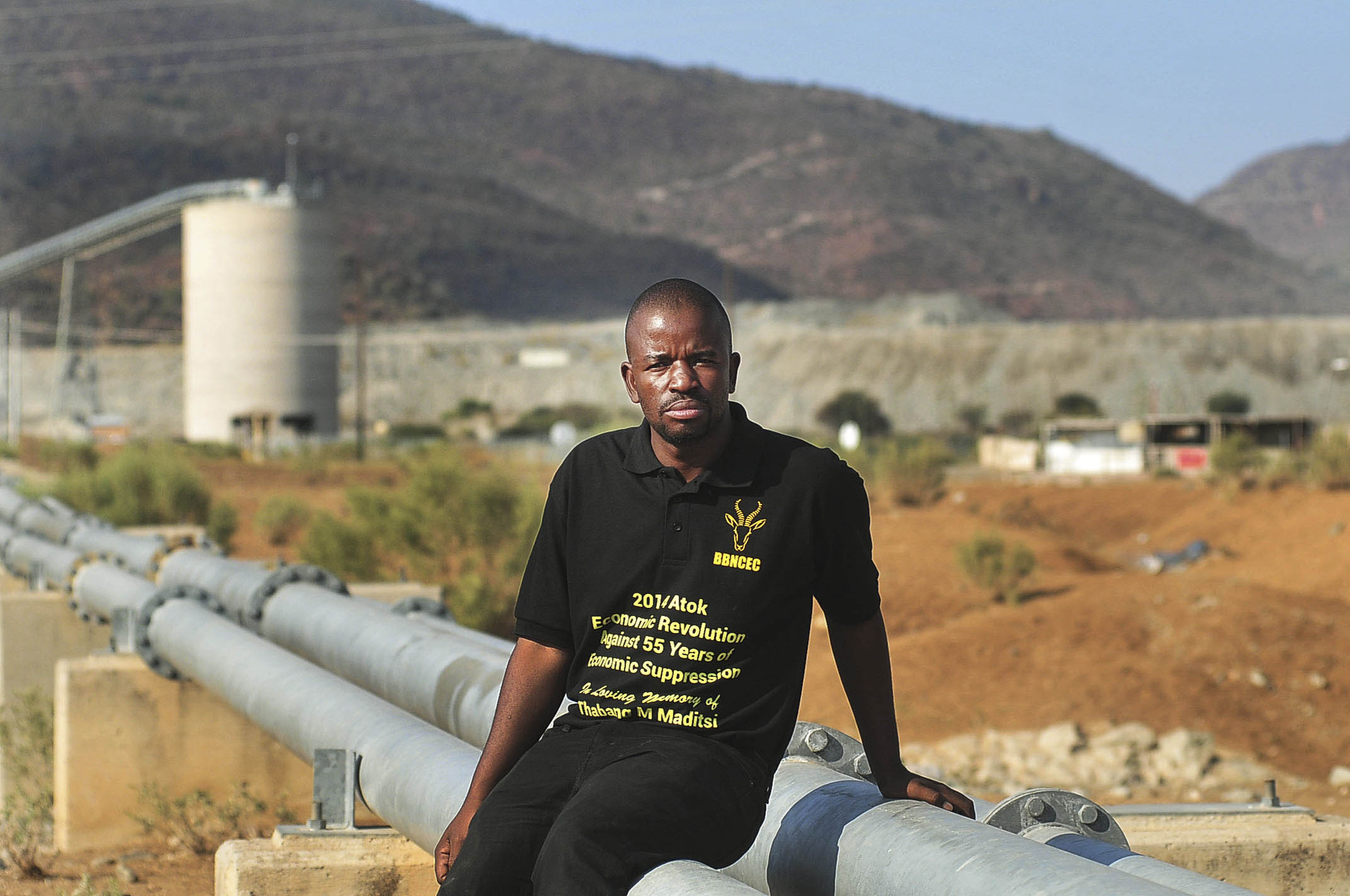

Stranded: Former mineworker Nelson Lesufi

Nelson Lesufi spends his days with his back bowed, fixing potholes, hoping for a welcome “loosey” (cool drink) as a respite from the unrelenting sun.

Life has been tough since he was retrenched. Still, he needs to earn a living and support his family.

He is among more than 4 500 workers who lost their jobs when the Bokoni platinum mine in Atok, Limpopo, was placed under care and maintenance in the middle of last year.

“Care and maintenance” refers to the process of a mine being closed and production halted, but with the possibility of operations resuming at a later stage.

The mine, which has operated under different names and owners for at least 55 years, was the economic heartbeat of the rural area about 90km southeast of Polokwane. Its closure has turned the once-vibrant village into a ghost town of sorts, where men loiter in the streets, stores that once buzzed with shoppers now have a trickle of customers and lodgings that earned property owners extra income are empty.

Limpopo has the biggest platinum deposits in the country and mining is a major contributor to the provincial gross domestic product, together with tourism and agriculture.

READ MORE: Dark days for platinum producers

On a weekday afternoon, Lesufi, dressed in shorts and a lime-green safety vest, works in the hot sun, fixing the potholes and repainting the speed humps on the relatively busy D4180.

Motorists slow down at the makeshift one-way stop-start on the road. Some drop coins into a container held up by Taetjo Maebele, also a former mineworker. Others hand out cigarettes, soft drinks and leftover food to the men.

Maebele and Lesufi earned a regular income at the mine, which is in Limpopo’s Sekhukhune district. But the owners of the mine, Atlatsa Resources and Anglo American Platinum, announced in May last year that they were suspending operations until December 2019.

Business Day reported that the joint venture owners were no longer prepared to carry on funding the mine, which had a cash outflow of R500‑million in the first six months of 2017. This was unsustainable in the short to medium term, given the current price of platinum.

“There’s a huge gap,” Lesufi says about the effect of the mine’s closure. “Life is too hard now.”

He had worked at the mine as a belt attendant since 2014, earning R5 700 a month, when he was retrenched last May.

Like many of those employed on the mine whose earnings sustained extended families in Atok and way beyond, Lesufi was just about able to support his mother, six unemployed siblings and three nephews. But without salaries, many are now stranded in this rural area, where life and business used to revolve around mining activity.

Nowadays, Lesufi is lucky to make R100 a day, which he shares with Maebele and two other men who assist them. But they have to use some of the money to buy cement and paint, which they use to maintain a road that was built by Anglo in partnership with the provincial government.

Maebele, like Lesufi, is a breadwinner; he has seven mouths to feed. He says that, since the layoffs, many people who worked on the mine have left the area and that theft has also become a problem.

[Bokoni Poultry Project has come to a complete standstill. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

[Bokoni Poultry Project has come to a complete standstill. (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

“People are even stealing goats [and] cattle,” says Maebele, who worked for four years at Bokoni.

The mine is surrounded by other villages that fall under the administration of at least three tribal authorities. Those families who do not rely on income from the mine are sustained either by remittances from migrant workers or subsistence farming. The only other job prospects are in government departments or at the municipalities.

Although the mine has always drawn labour from these areas, the only physical difference it has made are the scars it has left on the land and the transformation of some villages from subsistence farming hamlets into semi-townships that became wholly reliant on the mine’s existence.

Property owners took out loans to build lodgings to cater for the migrants who worked at Bokoni, known for many years as the Atok mine. Small businesses, hair salons, car washes, taverns, spaza shops, car repair workshops and hardware stores thrived. Hawkers also did a roaring trade selling goods to the men and women working at the mine.

But, with the mine closing and thousands leaving, Atok is struggling.

“Poverty in the area is out of proportion. Social life is disintegrating. We are dealing with the legacy of a mine that has mined in our community for over half a century without bringing about any project that doesn’t depend on mining,” says Lesedi Maphakane, the deputy secretary of the Baroka ba Nkwana Community Engagement Forum.

The committee represents 22 villages around the mine.

Atwell Lesufi, the secretary of the Atok Business Forum, which represents more than 100 businesses — including construction, trucking, catering, engineering, mining and maintenance supply companies that were subcontractors for Bokoni — says most of their members have shut up shop.

“There is no more business here. We don’t know what to do. We are desperate, stranded,” Atwell says.

[Community forum member Lesedi Maphakane says businesses in Atok were dependent on the Bokoni mine (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

[Community forum member Lesedi Maphakane says businesses in Atok were dependent on the Bokoni mine (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

More than 300 taxis that operated between Polokwane, Burgersfort, Lebowakgomo and Atok have been grounded, and many of the vehicles have been repossessed because they failed to make their repayments.

The two forums have now written to the department of mineral resources (DMR), asking it to force Atlatsa and Anglo to reopen the mine or lose their mining licence.

“There are no prospects of survival because life was dependent on mining. That is something we are trying to rectify,” Maphakane says.

Last month, Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe told a meeting of the Chamber of Mines that he intends to meet companies that have put their mining operations on hold.

“The high number of mines and shafts under care and maintenance contribute heavily to the massive decline in both production and employment. In this regard, we will meet with companies that are culprits of these practices. We intend to discuss honestly and robustly the ‘use it or lose it’ principle found in our law,” Mantashe said.

“Our mineral wealth must be exploited, not left unused, if we are to generate economic growth and [make an] impact on the development of society. It is in this context that we wish to invite mining companies that are involved in this practice to come and make presentations to the DMR on why this situation pertains,” he said.

[Now shops are empty and construction (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

[Now shops are empty and construction (Lucas Ledwaba/Mukurukuru Media)]

Maphakane says the economic decline in the area has led to a spike in many social ills, including domestic violence and crime.

He says that, although Anglo refurbished some creches, schools and roads in the area, it has failed to come up with any sustainable job creation projects in its social and labour plans.

He cites the aborted Bokoni poultry project, which was meant to create jobs, as one example of Anglo’s failed legacy. The project was supposed to form part of the 2013-2018 social and labour plan but construction, which is still at the foundation stage, has come to a standstill.

The committee argues that, because Anglo still has the mining licence for Bokoni, it has an obligation to kick-start the social and labour plans for the 2018-2022 period.

Maphakane says they have submitted plans to Anglo to build factories for manufacturing furniture and personal protective equipment, as well as a hydroponic farming project, but there has been no progress on these either.

“Our position is that if Anglo is not mining, they should transfer the licence,” Maphakane says. —Mukurukuru Media

Villagers press for absentee mining firms to ‘use it or lose it’

The Baroka ba Nkwana community in Atok, Limpopo, is the latest to add its voice to the growing calls for the department of mineral resources to take harsh action against companies accused of failing to use their mining licences for the benefit of residents.

The Baroka ba Nkwana Community Engagement Forum, which represents 22 villages in Atok, has written to the department, asking it to force Anglo American Platinum to reopen its operations at the Bokoni platinum mine.

The company placed the mine under care and maintenance last year, after a falling-out about a R4-billion debt with black economic empowerment partner Atlatsa Resources. The residents have asked the department to revoke Anglo’s licence and hand it over to them if the company fails to reopen the mine during the current financial year.

But the Baroka ba Nkwana’s expectations of such drastic action by the department may be too much. Even though the mineral resources department has in recent years threatened tough action against mining houses that fail to comply with the demands of their social and labour plans or do not use their mining licences, these threats have so far not been heeded.

Deputy Minister Godfrey Olifant told a heated gathering of informal miners in Burgersfort last year that the department was going to conduct checks on mining companies that didn’t comply with the social and labour plans and take action.

But the department’s response to Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe’s veiled threat to mining houses with suspended operations to “use it or lose it” suggests that such threats of action border on hollow political grandstanding.

“As indicated by the minister at the AGM [annual general meeting of the Chamber of Mines], the department’s approach is not to use the ‘use it or lose it’ principle as a first resort, but to rather engage with the companies placing shafts in care and maintenance to explore viable alternatives, in order to ensure minerals are not sterilised,” the department’s spokesperson, Ayanda Shezi, said.

After the department and the Baroka ba Nkwana committee met, Shezi said “a resolution was taken that there will be an audit inspection and a meeting with the management of Anglo, Atlatsa, [the department] and the community leaders before the end of this month [June]”.

The department said that in Limpopo there are nine mining operations under care and maintenance and that companies have indicated various reasons for this state of affairs, including adverse economic conditions and low commodity prices.

Regarding Olifant’s declaration last year that the department was going to probe mining houses abouttheir compliance with their social and labour plans (SLPs), Shezi said “the office is currently conducting SLP audits on the operating mines in Limpopo”.

She said where “corrective measures are necessitated by the findings, they will be taken as such”.

Responding to the Baroka ba Nkwana people’s demands that the department revoke Anglo’s mining licence, she said “the department remains committed to assisting communities, as would be necessitated by prevailing circumstances, within the ambits of the law”.

“In terms of any possible intervention by the department, the mine needs to indicate its intention of disposing of the assets,” Shezi said.

“In that case, the department will then advise in terms of transferring the right from Bokoni to the community, in line with provisions in the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act.”

Anglo American Platinum did not respond to questions by the time of going to print.-— Lucas Ledwaba, Mukurukuru Media