Leader of People’s Rainbow Coalition party Joice Mujuru addresses a presidential campaign meeting in Bulawayo in June.

POLITICS

The resignation of Robert Mugabe in November last year has brought a glimmer of hope for credible elections in Zimbabwe on July 30 after the many miscarriages of justice in the past three elections.

But, despite a great deal of advocacy and a much-publicised meeting by women from all walks of life with President Emmerson Mnangagwa in May, women’s representation in Parliament and local government will at best remain the same and, at worst, decline.

The unprecedented candidature of four women for president has been met with a sexist backlash and mudslinging, a reminder of the underlying patriarchal norms that define Zimbabwe’s ageing leadership.

Former vice-president Joice Mujuru, who fell out of favour with Mugabe and now leads the People’s Rainbow Coalition, has been called a witch. Movement for Democratic Change — Tsvangirai (MDC-T) leader Thokozani Khupe has defiantly stood her ground, maintaining that she is the constitutionally elected successor to the late Morgan Tsvangirai and not Nelson Chamisa, who leads the MDC Alliance. She has been subjected to a storm of social media insults, including being called a “hure” — Shona slang for a prostitute.

Riding the tide of the recent global feminist fervour, her right-hand woman and MP for Matabeleland South, Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga, wore a jumper inscribed “Hure, #MeToo!” when she went to hand in her nomination papers before the June 22 deadline.

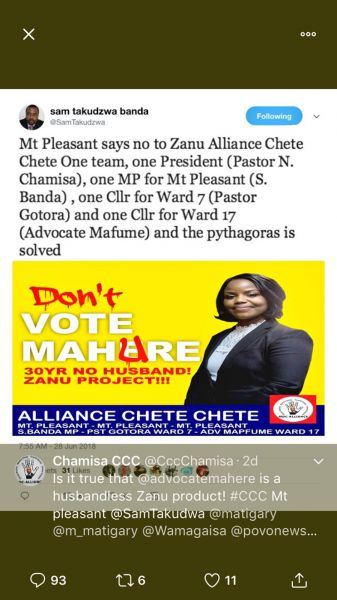

Blazing the trail for a new brand of young female leadership, independent candidate for the Mount Pleasant suburb in Harare and Cambridge- trained barrister Fadzayi Mahere has fought back social media derision about her not being married with tweets such as: “Marriage, though often a beautiful thing, is not an achievement. It does not qualify one for public office. It’s an irrelevant factor when we assess whether one will or won’t succeed. Individual character is the true test. Grace [Mugabe], after all, was married.”

A prominent member of the #ThisFlag Movement that galvanised public opinion against Mugabe, Mahere’s strapline is that “Africa’s future is bright and it is young.” Challenging the old boys network through prolific use of social media, she is running a refreshingly modern campaign calling for clean governance under her hashtag #Bethechange.

This year’s election, however, will go down as one in which Zimbabwean women spoke out but made little electoral headway.

Article 17 of the Zimbabwean Constitution adopted in 2013 guarantees gender equality in all areas of decision-making but the Constitution only spells out a quota for women in Parliament and not in any other areas, including local government.

Like most Southern African countries, Zimbabwe has a “first past the post” or constituency electoral system. The national quota, which borrows from a model honed in Tanzania, allows women to compete freely for these seats but reserves an additional 30% of seats for women only, distributed among parties on a proportional basis. This led to the representation of women in Parliament increasing from 18% to 35% in 2013.

The “temporary special measure” remains valid until 2023, so women are guaranteed 30% of parliamentary seats in the coming election. But the litmus test in the run-up to the expiry date in the next elections is whether more women can get into Parliament through the rough and tumble of campaign politics. In this, women have lost before the election is even held.

Analysis of party lists by the Women in Politics Support Unit shows that neither the ruling Zanu-PF, which has a 30% quota for women, nor the main opposition MDC Alliance, which boasted a 50% quota for women, have lived up to their manifestos.

According to the support unit, in the National Assembly, 47 political parties fielded candidates; 20 of these did not field any women candidates at all and two parties fielded only one woman each. In total, women comprise a mere 15% of candidates. Eighty-four out of 210 constituencies will be contested by men only. In the dog-eat-dog contests where women are standing, there is no guarantee of them winning.

“We are deeply concerned that, at this point, it appears that the only women that will be in Parliament are the 91 that are required by law. This brazen disregard for the basic tenets of democracy is deplorable 38 years after independence,” the support unit said in a statement last week.

Frantic advocacy efforts led by the Women’s National Coalition have been diverted to a constitutional amendment to preserve the quota beyond 2023. These efforts overshadow the fact that at the local level, arguably an even more important area for challenging social norms, there is still no quota at all. In 2013, the representation of women in local government in Zimbabwe dropped from 18% to 16%, a downward spiral that seems likely to continue in 2018.

According to the support unit analysis, 40 political parties fielded candidates for the local authority elections. Of these, 12 fielded men only. Women constitute a mere 17% of the 6 796 candidates.

As the chances of all these women winning their seats are slim, the likelihood of women’s representation slipping below even the 2013 figure of 16% is high.

This blow is all the more devastating because of the concerted campaign over the past five years to press home the point that the absence of special measures at the local level is in violation of article 17 of the Constitution. In 2016, representatives of the ministry of local government, justice and parliamentary and legal affairs and the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission went on a study visit to Mauritius to learn how the government there increased women’s participation at the local level fourfold (from 6% to 28%) thanks to a gender-neutral quota.

With technical support from Gender Links and UN Women, they made a submission to Parliament, followed up by the Women in Local Government Forum.

In March 2018, the Zimbabwe women’s parliamentary caucus in partnership with civil society launched the Women’s Manifesto with five priorities: economic development, social services, transport and infrastructure, access to justice and equal benefit of the law, and women’s representation in governance.

Women from all walks of life converged to share their issues and concerns. An extension of the quota at national level beyond 2023 became the major focus, with the Women in Local Government Forum calling for the quota to be extended to local government.

In May this year, Zimbabwean women got the chance to meet Mnangagwa to discuss the difficulties they face. Women’s representation in local government took centre stage.

He reiterated the government’s commitment to the African Union Charter, which requires that member states have equal representation of women across the board. Despite his accessibility and more debonair approach compared with Mugabe, Mnangagwa has not walked the talk of gender equality where he has the most obvious power to do so — in his Cabinet. Women constitute five out of 30 (17%) of Cabinet ministers, and none are deputy ministers. Many of the most senior Cabinet posts went to appeasing army generals who helped Mnangagwa to unseat Mugabe in what some analysts have called a coup in all but name.

A highlight of the 2018 Zimbabwe elections is the presidential election, which have witnessed a record 23 candidates, of whom four are women. At 17%, it is the largest number of women to ever have competed for the highest office in the land. The candidates are Melbah Dzapasi (#1980 Freedom Movement Zimbabwe), Khupe (MDC-T), Violet Mariyacha (United Democratic Movement) and Mujuru (People’s Rainbow Coalition).

Khupe and Mujuru are household names in Zimbabwe. Mujuru will bank on her contacts and experience as a former Zanu-PF legislator and possibly steal some votes from Zanu-PF as well as garner support from other sectors in Zimbabwe, though she has not been so visible on the campaign trail.

Khupe has her following from the MDC factions, which will also have a bearing on the road to State House. But the bets are for a run-off between the top two candidates, Mnangagwa and Chamisa, or the formation of a government of national unity.

The chances of a woman president are almost nil but the race itself has given women visible platforms to take a defiant stance. Misihairabwi-Mushonga vowed to resist threats by the party’s top leadership to recall her from Parliament owing to her support for the expelled Khupe’s breakaway faction.

“I am chairperson of the parliamentary committee on gender and youth affairs and‚ therefore‚ cannot be persecuted for attending a solidarity tea for a woman who is basically under siege from male chauvinists. I am a women’s activist and that defines who Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga is. Nobody will take that away from me and not even a party can do that‚” she said.

Priscilla Misihairabwi-Mushonga wears a ‘Hure’ T-shirt in support of the MDC’s Thokozane Khupe.

In another interesting twist that carries hope for the future, young women have found their voices and are demanding a 25% quota for young women in politics. Decrying the likely backtracking for women in the coming elections, the Institute for Young Women Development aired their frustration with stifling patriarchal norms in an open letter to political leaders.

“We believe that more young women in leadership, especially at local government level, will promote gender-responsive service delivery because young women are primary consumers of these services,” they declared. Their clarion call — “nothing for us without us”, building a society inclusive of women and youth — will be one of Zimbabwe’s biggest challenges long after the election results are announced.

Colleen Lowe Morna is chief executive of Gender Links and Tapiwa Zvaraya is the organisation’s Zimbabwe monitoring and evaluations officer