(John McCann/M&G)

South Africa has finally signed the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement, but the journey towards creating a common market of goods and services on the continent will be challenging, if history is anything to go by.

The agreement seeks to remove tariffs and nontariff barriers on the trade in goods to deepen economic integration, loosen restrictions on the trade in services and ease the movement of people across Africa.

Last Monday, President Cyril Ramaphosa finally put pen to paper, joining the 44 countries that had signed the agreement in March.

Nigeria and South Africa, the biggest economies on the continent, initially held back on signing the agreement when it was launched in Kigali, Rwanda. At the time, South Africa said the agreement had to be vetted by state law advisers; Nigeria said it wanted to protect local industries from cheap imports being “dumped” in the country. Nigeria has still not signed but has launched a broad consultative process with various stakeholders to decide whether it should join.

At present, the agreement is merely a commitment in principle from heads of state to create a more integrated market across the continent and will only come into effect after at least 22 countries formally ratify it.

But experts say the benefits of the agreement will be limited if policymakers do not tackle the systemic and structural issues that have stifled other free trade agreements before.

The agreement is designed to improve trade between the continent’s 55 countries, with their combined gross domestic product of between $2.2‑billion and $3.4‑billion. A statement by ratings agency Moody’s said intra-African trade only made up to 15% of the continent’s total trade, up slightly from 11% in 2008.

Asmita Parshotam, trade expert at the South African Institute of International Affairs, said in a report that intra-African trade has only averaged 12% to 14% of the continent’s total trade basket over the past 20 years.

“We go on to sign these agreements at the regional and continental level but the bottom basics have not been resolved,” said trade expert Tinashe Kapuya.

Many African countries sign these agreements without fully assessing the impact they will have on their commitments, which results in misalignment with their national policies, Kapuya said. This hinders implementing free trade and “sometimes they don’t want to amend their legislation because they don’t want to open up their markets”.

These countries want to protect their industries from markets such as South Africa, which are more advanced and competitive and would possibly dominate their domestic markets, close down businesses and cause job losses, Kapuya explained.

Parshotam noted that the agreement should be able to protect the needs of less-developed countries with smaller and weaker economies, so that everyone can participate.

“The [agreement] has to find solutions that militate against protectionism and cater for the needs of both low-developed countries and larger economies such as Kenya, Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa,” she said.

She added that it could prove to be difficult to eliminate tariffs in the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement if one looked at how other regional trade agreements have played out.

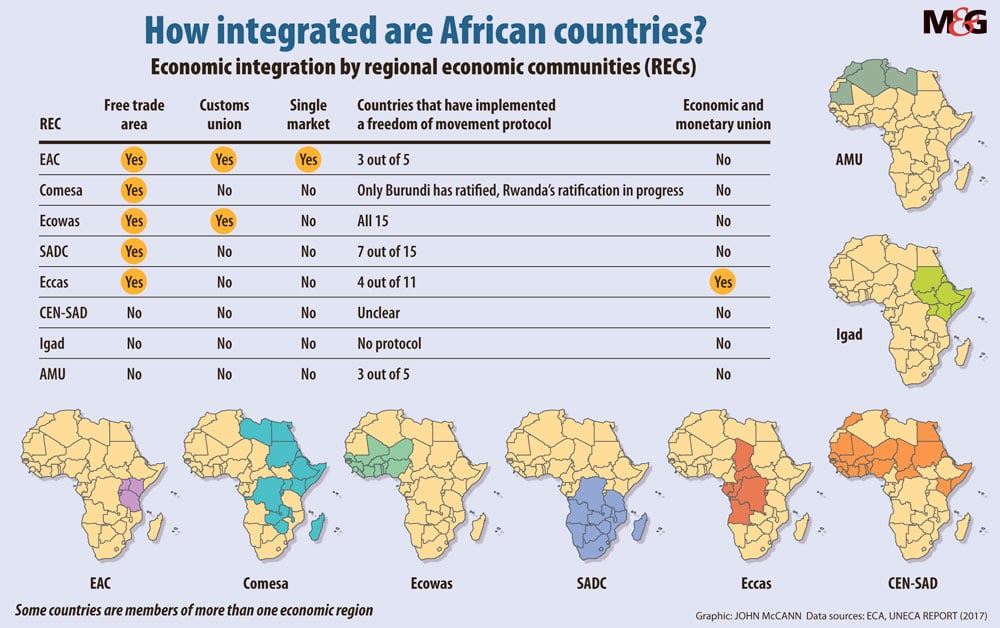

The East African Community and the Economic Community of West African States are the only regional trade areas without tariffs among their member countries. “Mauritius is the only SADC [Southern African Development Community] country that imposes no import tariffs on either SADC or Comesa [Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa] trade,” Parshotam said.

Kapuya said countries such as Malawi rely heavily on tariff revenue, to the extent that part of its national budget depends on taxing products from other countries. Removing these tariffs would, in effect, deprive those countries of part of their fiscal base, Kapuya said.

This is why the SADC free trade agreement has not worked, he said.

“When countries take down tariffs, they started increasing nontariff barriers … which makes it extremely difficult to trade with other countries, to the extent that you still [cannot] export [to neighbouring countries],” he said.

Moody’s said nontariff barriers — such as ineffective customs documentation and corruption — were a major issue on the continent, and the World Bank has estimated that “the costs for intra-African trade are the highest among developing regions, and around 50% higher than in East Asia”.

Meanwhile, countries with larger manufacturing bases are in a better position to tap into the benefits of further trade integration.

According to Moody’s, South Africa, Kenya and Egypt are likely to be the biggest winners “thanks to their large manufacturing bases and relatively robust infrastructure, particularly given their access to electricity”. They were followed by Morocco, Namibia, Tunisia, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and Cameroon.

“There is a sense that Nigeria had a problem with trade agreements lately,” Kapuya said, noting that the country had also refused to sign the West Africa-European Union Economic Partnership Agreement.

“I think it’s okay for countries to take time to reflect on agreements, especially if they have far-reaching consequences. These free trade agreements have the potential to affect countries in a major way — it can be positive and it can be negative,” Kapuya said.

Speaking at the International Press Institute World Congress in Abuja in June, Nigeria’s finance minister, Kemi Adeosun, explained why Nigeria decided to consult before signing the agreement. “It’s not about speed; it’s about doing it right,” she said.

“We have to deal with an agreement of that nature in a way that is win-win. There’s no country that works against its own interest, even for love of its continent or region. What we are hoping is [that] all the stakeholders will be involved in the way forward as well, so that this is not a case of government telling the business community what to do,” said Adeosun.

African countries will continue to discuss the agreement for the rest of this year. There are still outstanding issues to address related to tariff concessions, trade in services and rules of origin. A second phase of negotiations on intellectual property, investment and competition policy is due to begin at the end of 2018.

There have been concerns that the negotiations have neglected “new-generation” issues such as the impact of the fourth industrial revolution on trade relations and industry.

“Negotiators’ apparent reluctance to [address this] raises questions as to how the agreement will cater for African countries leapfrogging their development into the 21st century, and what this will mean for their trade relations with third parties,” Parshotam said.

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust financial journalist at the Mail & Guardian