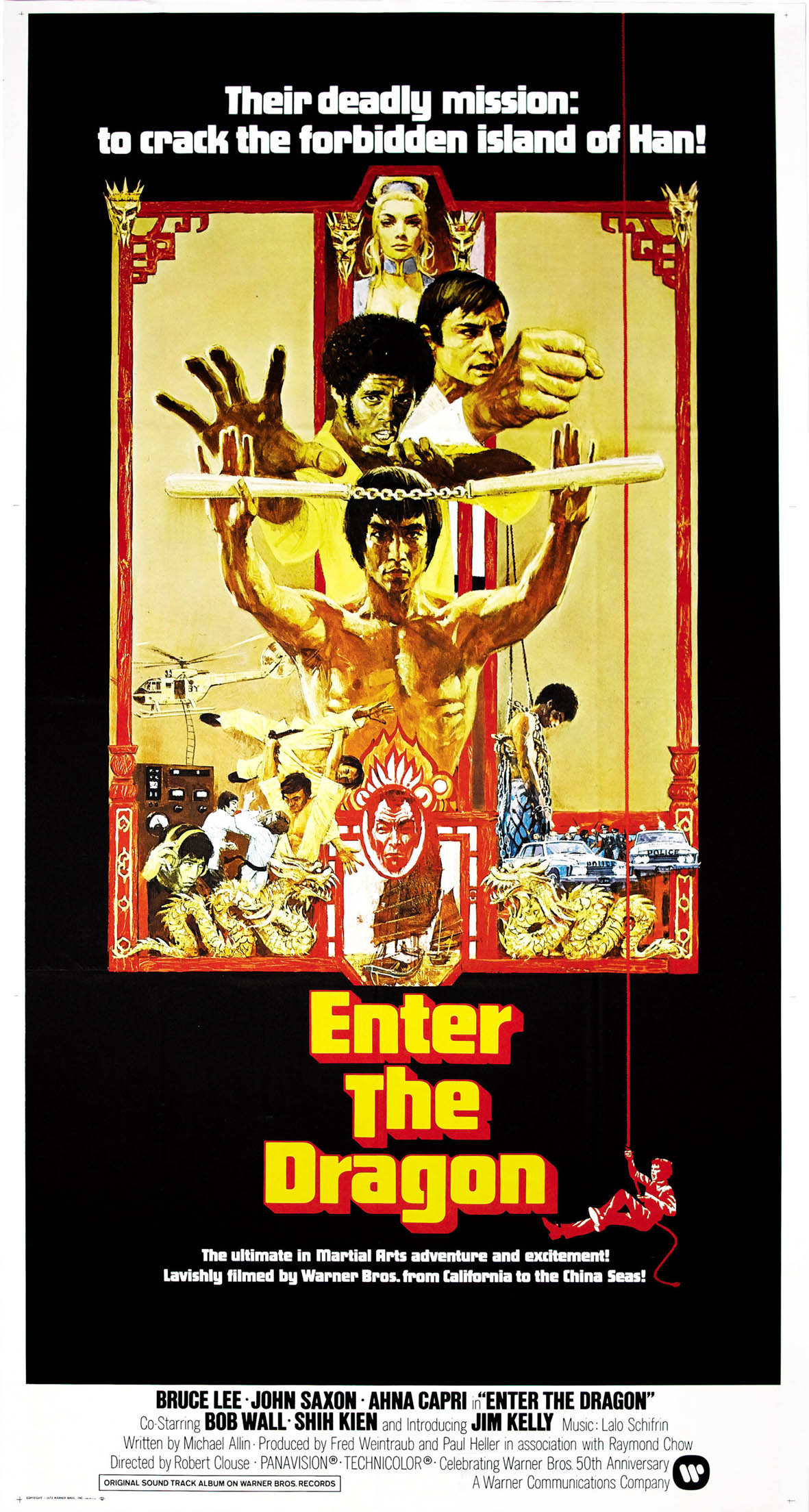

Dragon energy: Kung-Fu legend Bruce Lee was an icon of the martial arts boom

A year before Soweto was engulfed in the student uprisings of 1976, my father saw Bruce Lee’s film, Enter the Dragon, at the San Souci Bioscope in Kliptown.

The cinema, which served as both a musical and political hangout in the 1950s, provided a form of escapism for young black boys trying to survive the bleakness of apartheid. Although my father was a staunch fan of the nihilistic heroism of Clint Eastwood’s spaghetti westerns, it was Lee who provided a reprieve from the police raids, teargas and gunshots that would mark his generation’s lives.

Lee was also the first to use film as a way of selling kung fu as both an art form and a philosophy. The image of a marginalised man taking pride in his culture and tradition was enough to convince a generation of black men to see the beauty in themselves through martial arts. After watching Enter the Dragon, my father enrolled in martial arts lessons while developing a political consciousness in response to the world around him.

[Motivator: Enter the Dragon inspired a generation of black men by championing the underdog]

I first watched Enter the Dragon in late 2003 on a local television station. Like many children who spent part of their childhood without the gluttonous variety of DStv, I’d grown accustomed to watching intense soapie marathons, rom-coms set in Manhattan, and action movies starring legends like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone.

Along with my brother and my cousin, I developed a love for movies focused on the lives of the underdog or the good guy. These men, because they were always men, were filled with enormous potential, which remained unexplored and untapped because of the relentlessness of life.

These films held my interest and attention despite local television’s affection for inserting adverts at cliff-hanging moments. But as thrilling as it was to see Schwarzenegger blast a group of “terrorist” guerrillas in Predator or to watch Stallone train hard enough to take on the heavyweight champion Apollo Creed in Rocky, I yearned for something more.

Perhaps it was a desire to see the women in these films play a bigger role than the supportive girlfriend or the concerned mother? Maybe I wasn’t sold on their bravery, having spent evenings listening to my grandparents recount the turbulent years of underground activism in Soweto during the 1980s.

In hindsight, I realise that, like my father, I needed stories that aligned with the new ways in which I was beginning to relate to the world. The United State’s invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 and Iraq in March 2003 made a distinct impression on me as an 11-year-old. Before then, I had considered the so-called “land of the free and home of the brave” as the only place that would accommodate my active imagination and curiosity. From the films and television I’d watched, the US seemed fair to all of those who lived under it. Conversely, South Africa, with its stark inequality and shaky rainbow nation, seemed incapable of shedding its failures.

But when then-president George W Bush embarked on a bombing spree in the Middle East, I learned that the Yankee freedom packaged and sold to the rest of the world was built on a minefield of lies, gunpowder, conquest and destruction.

Stallone’s Rocky Balboa and Schwarzenegger’s Major Alan “Dutch” Schaefer came to represent an individualistic valour slicker than an oil rig stamped with flags of red, white and blue. These men were uncritical of how the quality of their lives were controlled by a country that preached bootstraps politics to the bootless. I thought of them as counterfeit rebels who followed rules instead of making ones of their own.

When I watched Enter the Dragon, however, I understood why it meant so much to my father.

I knew what I’d been missing in those action films: a protagonist whose interests lay with protecting and preserving his people and culture.

Released on July 26 1973, six days after Lee’s tragic death, the film has since grossed over $200-million worldwide and catalysed Hollywood’s interest in martial arts.

In case you haven’t seen it, the film tells the story of Lee (Bruce Lee), a talented and diligent student of the Shaolin Temple who’s tasked with taking down Han, a criminal running a drug and sex trafficking ring on an island off the coast of Hong Kong. Lee goes to the island under the guise of participating in a martial arts competition. Han, a former monk in the Shaolin Temple, is also behind the killing of Lee’s sister and mother, whose deaths he seeks to avenge.

The audience is then introduced to the two men who will help Lee in his quest to defeat Han — one of them is Williams, played by Jim Kelly, an African-American martial arts fighter and former Vietnam veteran who is ambivalent about his country and about life in general. In one scene, Kelly takes a boat to the island where he’ll participate in Han’s martial arts competition. As he looks around at the poverty around him, he says: “They don’t live too good over there. Ghettos are the same all over the world — they stink.”

His remarks are a nod to the social consciousness embedded in most Blaxploitation films and the popularity of Black Power sloganeering in popular culture. The other co-star is John Saxon, who stars as Roper, a listless white American who also served in Vietnam. Like Kelly, Roper’s allegiances lie with martial arts, not the flag. Both men overcome their apathy and individualism to help Lee put an end to Han’s criminal activity. In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, a dynamic Lee faces Han in a room filled with over 8 000 mirrors. The multiple reflections show his body contorting, flexing and leaping at a speed that confuses the line-up of Han’s men trying to pin him down.

[Bruce Lee in the room of mirrors in the 1973 film ‘Enter the Dragon’ (Warner Bros)]

He defeats Han and restores dignity to the Shaolin Temple.

In the past few years, discussions about cultural appropriation have forced the Western world not to treat the customs and traditions of the marginalised as a cheap costume.

Through the power of social media, an awareness has been established about the dangers of fetishising and commodifying certain cultures for the sake of appearing trendy. However, some of these discussions arguably fail to acknowledge that cultural exchanges between different groups are more fluid and complex than the butchering of certain slang, or the treatment of cultural clothing as fancy dress.

The martial arts boom that followed Enter the Dragon saw young black boys and men across the diaspora begin to use different fighting styles within East Asian culture to assert and take pride in their identity.

And in the 45 years since the film’s release, it’s clear how much Lee made a generation of black boys and men, including my father, feel more like themselves.