Dispossessed: Siona O’Connell’s documentary Uitgesmyt depicts the violence of the forced removals experienced by a small farming community in Elandskloof

About midway through the documentary Uitgesmyt, a news clip — no longer than 45 seconds — shows how, in 1996, to the sounds of a marching band, hundreds of people returned to Elandskloof, the small farming area from which they were forcefully removed in 1962.

“Our dream has come true today. Today, I am very happy,” a woman tells a TV news reporter, as fellow residents dance, hands waving in heady abandon.

Those returning to the area, about 120km from Cape Town, were the beneficiaries of the country’s first successful land restitution case.

But their joy was as fleeting as that news clip.

A collaborative project between the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Curating the Archive and the University of Pretoria’s department of historical and heritage studies, the 26-minute documentary was produced and directed by African studies lecturer Dr Siona O’Connell.

O’Connell says she was asked to work on the project “because of my interest in making films, but also because of my work around memory and trauma and forced removals”. Because her grandparents were forcibly removed from District Six, O’Connell describes herself as the “offspring of the colonial project”.

Her research interests pivot on “colouredness”, memory and trauma and how to think about freedom after apartheid. She has curated exhibitions and has directed and produced films including the 2015 documentaries An Impossible Return, about forced removals in Cape Town, and The Wynberg 7, about the student protests of the 1980s, as well as Promises and Lies: Fault Lines in the ANC, which was released in 2017.

She is currently writing a book about forced removals in Harfield Village, Cape Town, which is due for publication in 2019.

In Uitgesmyt, she turns her auteur’s lens not only on forced removals but also on the gaping holes in the land restitution process.

Loosely translated as “cast out”, Uitgesmyt is the somewhat crass Afrikaans word O’Connell used as a title because, she says, “it conjures up everything that has to do with something being dirty and kicked out”.

“When Margie January, one of the women I interviewed, used the word, I knew in a heartbeat that that was going to be the title. It’s such a powerful word. So difficult to translate,” she says.

It was while working on another project in the area that O’Connell says she “stumbled on Elandskloof by mistake”. “It’s really in the middle of nowhere. If you blinked you could miss it, because it really is this derelict little place. It’s surrounded by these really beautiful mountains so, on the one hand, for a filmmaker, the aesthetics of the place are just beautiful — until you go and you see these people …” she says, her voice trailing off.

She goes on: “What drew me to this work was to talk about the intergenerational effects of this kind of trauma as well as its subsequent effects on cycles of poverty — poverty begetting poverty and violence begetting violence.”

Her exploration of the history of the area — a mission station established by the Dutch Reformed Church — and interviews with disheartened returnees, she says, “brought home to me the long shadow of our past”.

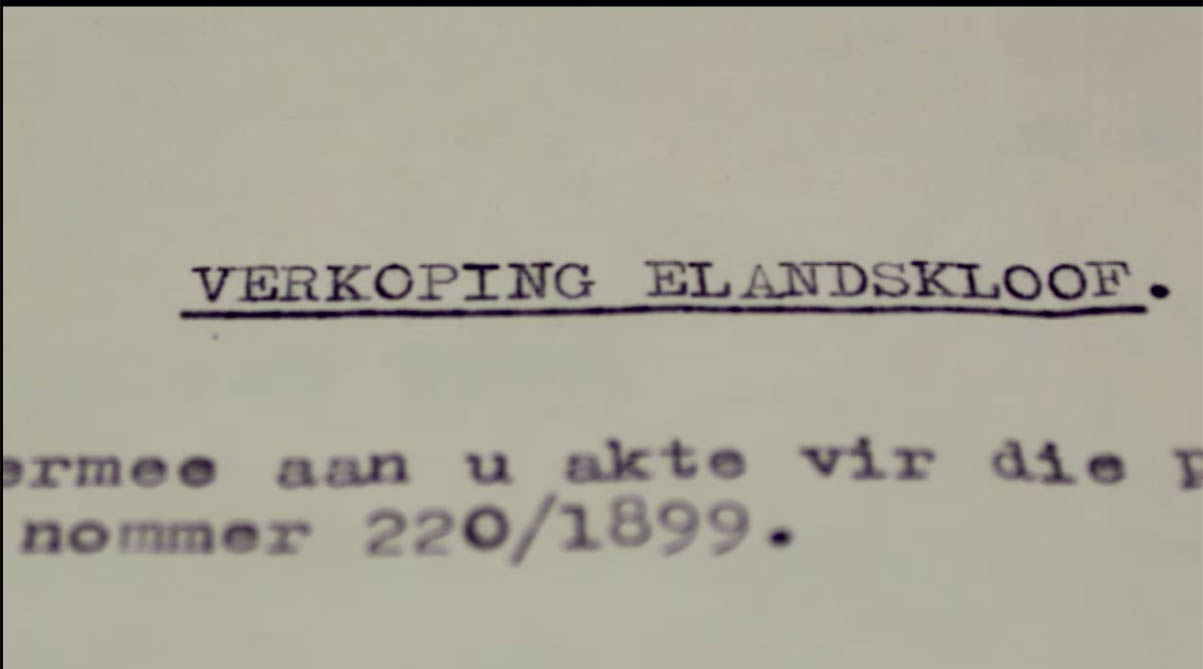

After being duped into believing the land they were paying for through the church would eventually be theirs, residents were removed after the land was sold to large-scale farmers.

O’Connell says the women she interviewed “would tell you that small-scale farming is in their blood”.

“They used to farm buchu, rooibos and cedarwood. But since rooibos farming became more controlled … they can’t do it any more because it’s illegal to farm rooibos without a permit. So, not only are they in the middle of nowhere, with no infrastructural support and dealing with the trauma of what happened in 1962, but they are unable to resort to what they knew best, which is small-scale farming,” she says.

“So now they are left to pick up acorns — these women in their 80s and 90s — collecting them to sell to farmers for livestock feed.”

[Empty promises: The Elandskloof community, forcefully removed from their land in 1962, was the first successful restitution case in post-apartheid South Africa. Yet the way the process unfolded has left the community members feeling frustrated 18 years after their historic victory]

With its focus on the effects of dispossession, Uitgesmyt is a timeous addition to the land debate currently hitting fever pitch nationally.

Thousands of people across the country have, over the past few weeks, been making oral submissions to the joint constitutional review committee on whether section 25 of the Constitution should be amended to allow for the expropriation of land without compensation.

Earlier this year, the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces mandated the committee to review this section. More than 700 000 written representations on land expropriation were submitted by the public.

O’Connell views the hearings as important. Although wary of “the political messaging that is being driven [because] the land issue is going to be so central in the 2019 elections”, she adds: “While the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission] dealt with gross human rights violations, it did not touch on other human rights violations like the Group Areas Act, and I think the chickens are now coming home to roost.”

But, O’Connell believes, there is one glaring omission in how the country is addressing the land issue — something that, years after the celebratory sounds of that marching band has faded, she has witnessed first hand in Elandskloof.

“There is a lingering, festering anger. That what they were promised has not come to fruition. And there is this deeper, traumatised community. There is a deep trauma that is festering,” she says. “We need to pay sufficient attention to the trauma caused through forced removals — otherwise we will jeopardise any potential successes of any restorative programmes.”

O’Connell adds: “I would hope that, alongside these public hearings, we come to understand that the matter of restitution cannot be a monetary one or simply the return of land. Some attention — no, significant attention — has to be paid to trauma and memory counselling around what happened through forced removals. It can’t be as simple as just getting back land or cash.”

Uitgesmyt will be screened at the University of Pretoria in August. For details, email [email protected]

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation‘s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian