Earthly: Mphuthumi Ntabeni's book traces Eastern Cape landscapes with their often bloody histories.

THE BROKEN RIVER TENT

by Mphuthumi Ntabeni

(Blackbird Books)

When first we meet Phila, a modern Xhosa professional and the protagonist of this novel, he is attending a protest meeting on evictions in Hout Bay.

In a flashback to 10 years earlier, we find him reading in the sun outside Port Elizabeth tourist attraction Fort Frederick. In a swift stroke, the writer, Mphuthumi Ntabeni, throws his readers into the deep end by drawing together the power of colonial Britain and new forms of imperialism, invoked by a busload of Chinese tourists walking past Phila, and by the book he is reading, which is written by medieval Roman Christian philosopher, Boethius.

This philosopher lived at the time when the mighty Roman Empire came to an end and was ruled by the first king of Italy, Odoacer, who was, by all accounts, a “barbarian”. Boethius’s most well-known work is the Consolation of Philosophy written in 524 BCE in which he examines the turning wheel of history.

Fort Frederick was built in 1799, before the 1820 Settlers arrived. It was built to defend the Cape Colony against a French invasion; the first in a string of British forts along the frontier zone.

Phila, formerly a practising architect, is now engaged in writing a history of the Eastern Cape.

“It was easy to be indifferent within its village soul, stubborn colonial character and bland industry,” he thinks of Port Elizabeth. “Its pleasing forlornness was the natural habitat of his melancholic spirit.”

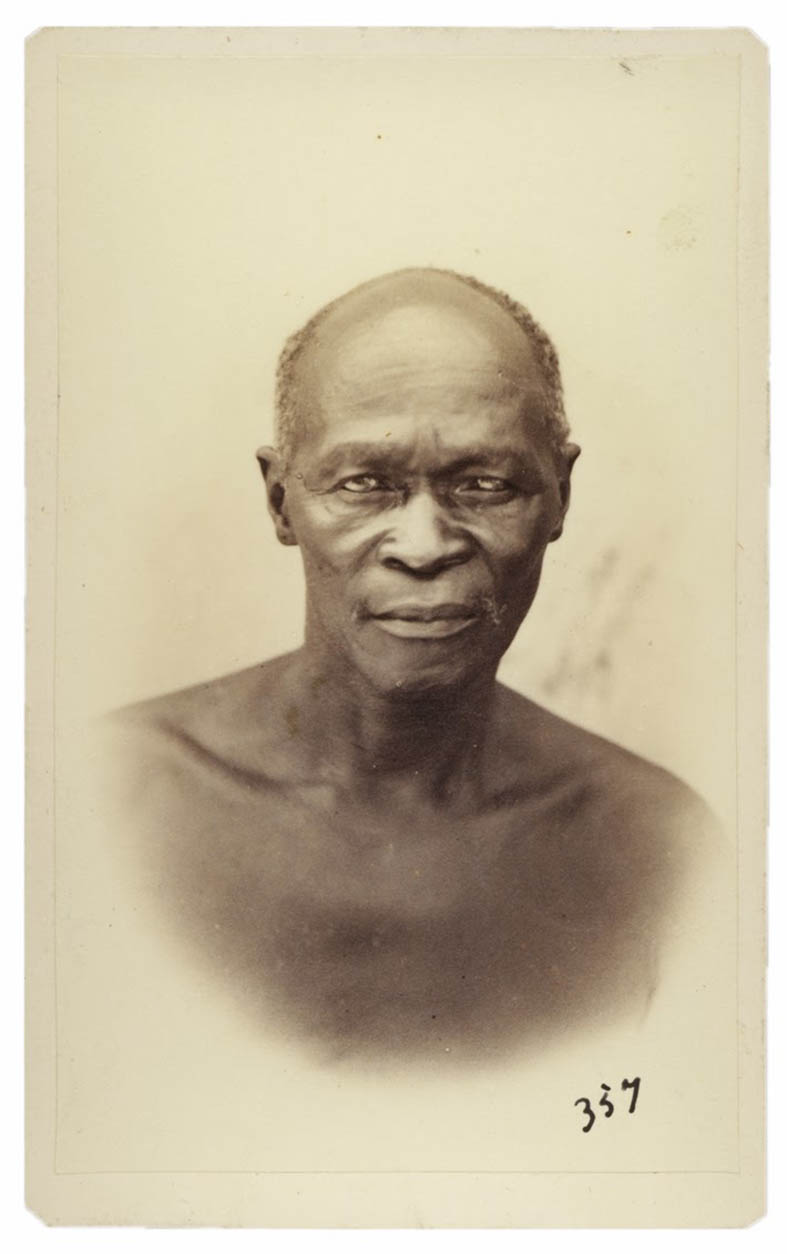

But this bunkered-down life is about to change for Phila, because he has been chosen by his ancestor, Maqoma — the great military general and chief of amaRharhabe. Maqoma fought the scourge of the colonial British in the Eastern Cape Frontier Wars and was eventually imprisoned on Robben Island, where he died in 1873.

[The calling: The ancestral spirit of the great military general and chief of amaRharhabe, Maqoma. Maqoma guides the protagonist through the history of colonialism (4 November 1863)]

He comes to life in Phila’s analeptic memory. Maqoma — “a stocky, muscular, prune-faced man … wearing traditional Xhosa clothes and a leopard skin blanket” — first appears to the protagonist on a bus. His many appearances are entirely convincing, as Phila, at first reluctant and disbelieving, is drawn into conversation with this old man who speaks archaic, formal isiXhosa that adds gravitas to his stories.

These conversations are often amusing. Maqoma, for instance, is amazed that a whole district has been named after Makhanda, but nothing is named after him even though he was a far more effective and persistent fighter than Makhanda (also known as Makana Nxele).

But, leavened as these conversations are with humour, scepticism and insight, Maqoma’s revelations are also deeply moving and often heartbreaking. He launches the reader into the 19th-century Eastern Cape, describing the mountains and rivers, which Maqoma calls by their old names.

The Xhosa people are often called the River People, and rivers are sacred places invoked by many prophets.

Ntabeni’s novel paraphrases a line of TS Eliot’s poem, The Wasteland, and gives poetic expression to the devastation of the Xhosa people during the Frontier Wars.

Phila at first feels he may be a little mad and wonders whether the visions are an effect of his father’s recent death, but comes to accept that Maqoma may suddenly appear for a chat.

Phila’s psychologist friend with benefits thinks he is not well and loses patience with him, resolving to betray his confidence to a white colleague, who superciliously remarks on Phila’s “somatic delusions”. But Phila brushes off this diagnosis and is drawn ever deeper into appreciating what Maqoma is telling him, accessing ancestral memory.

This complicated history is interspersed with Phila’s reality. When we meet him, he is already in his 40s. He’s an architect trained in Berlin and has a good command of German.

In him we are shown the complexity of colonialism. He is a keen observer of racism and the workings of white privilege. He especially avoids white people who trot out the phrase “You people”.

In the decade covered by the novel, Phila becomes close to three different women. These relationships are particularly well described, with insight and honesty, as Phila realises his own unreadiness for a shared life.

In search of the forgotten or misremembered history of the Xhosa, Phila travels around the Eastern Cape — to the cities, the mountains, the rich farming land below the Amathole and the old mission stations. Maqoma meets him in these places and recounts their history in considerable detail.

Quite often geography dominates chronology, but we learn about the fragmented state of the Xhosa people after white people came in their numbers.

Maqoma also discusses the role of the prophets and describes how he was defeated in the first battle that he commanded, against Ndlambe who followed up as brutally as the British would, later.

Maqoma’s greatest victory comes in the Eighth War of Dispossession, between 1850 and 1853, in which he gains the alliance of the mainly Khoikhoi settlers of the Kat River Settlement, previously Maqoma’s territory. With the help of these Kat River rebels, Maqoma holds the Waterkloof north of Fort Beaufort and resists all efforts to evict him from there for over a year.

Maqoma’s voice, clever, observant and unrelenting as it is, carries this novel in a powerful wave. He emerges as a man with opinions about his fellow chiefs, their strategies to retain power as well as how they were influenced by men of religion, making many fine distinctions between different forms of the old religions, as well as the degrees to which they were altered by contact with the Christians.

Maqoma and Phila have a preference for the early Presbyterian missionaries, dismissing the Wesleyans and Anglicans as a bunch of imperialists. Maqoma has a special affection for one missionary, Reverend Van der Kemp, and even describes Coenraad de Buys, as benign and willing to integrate with Xhosa people. Maqoma is often disparaging about the Mfengu, but is more accepting of the Khoikhoi.

Any writing of history is subject to the possibility of bias and misrepresentation and it is impossible to achieve perfect accuracy and fairness. And because this is a novel, not a history text, it is not that serious that Ntabeni is a little misleading when he describes the ambush and killing of Lieutenant Charles Theodore Bailie and his platoon of 12 Khoikhoi Cape Mounted Riflemen as though it was part of the Waterkloof campaign in 1850, when it actually happened in 1836 in a different part of the Eastern Cape.

Maqoma tells this story in his discussion of the ineptness of the British troops, hindered by their heavy uniforms and stuck in old ways of soldiering, no match for Maqoma’s swift, nimble warriors who use guerilla tactics and soon found ways of acquiring guns and horses to even the odds.

The narrative proceeds with vigour, now and then slowed down by historical detail (which many will enjoy), but the dialogue between the two: the modern Phila, steeped in Eurocentric education, and Maqoma, who has the wisdom of history, hindsight and age, leads the reader on.

There are a challenging number of Eurocentric and Western cultural references that come up mostly in Phila’s stories, but also in Maqoma’s, who has met some interesting thinkers in the next world.

Both Maqoma and Phila describe the beautiful forests of Mthonti, the many rivers, the fearsome mountains full of caves and the ravines that offered refuge to the embattled Xhosa. Phila notes the “insouciance of nature”, that all these are still there, despite the bloody events that have swirled around them.

Although Phila seems to be asking who are we without our history and Maqoma believes it needs to be told and spoken about, many characters in the book are profoundly ignorant and quite indifferent to their history.

Hopefully readers will also find this a mesmerising read. Maqoma’s story is so powerful and, though he died a prisoner of the colonial British, his name resounds with valour and dignity and his life should be made known to all of us. This rich and erudite novel will help to achieve this.