Good shot: Nomvo Booi is seen here with comrades at the Bamagamoyo camp at Mothopheng Military College in Tanzania (Supplied)

Mam’Nomvo “Poqokazi” Booi was the first woman to be imprisoned for matters linked to the armed struggle against apartheid. That was in 1962 in Ngcobo.

Born on May 16 1929 in the village of Zagwityi in Gcuwa (Butterworth), Nomvo Booi was the 11th of Nkumbikazi and James Booi’s 13 children. She was bright but self-effacing. During her school days at Zagwityi Primary School, when other children didn’t know the answer to a question put to them by their teacher, Theophilus Pamla, he would often say: “Tell them, Nomvo.”

Following in the footsteps of her siblings, she dismissed any interest in academia and pursued a career in dressmaking and design at the Clarkebury Institute in the Ngcobo district. After that, she established and ran a successful design and dressmaking business in Gcuwa and later in Queenstown before she became politically involved.

Her journey with politics began when she joined the ANC as a member of the youth league at a time when its members disagreed with the leadership and subsequently broke away to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). That was in 1959 under the leadership of Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe. Booi was 23.

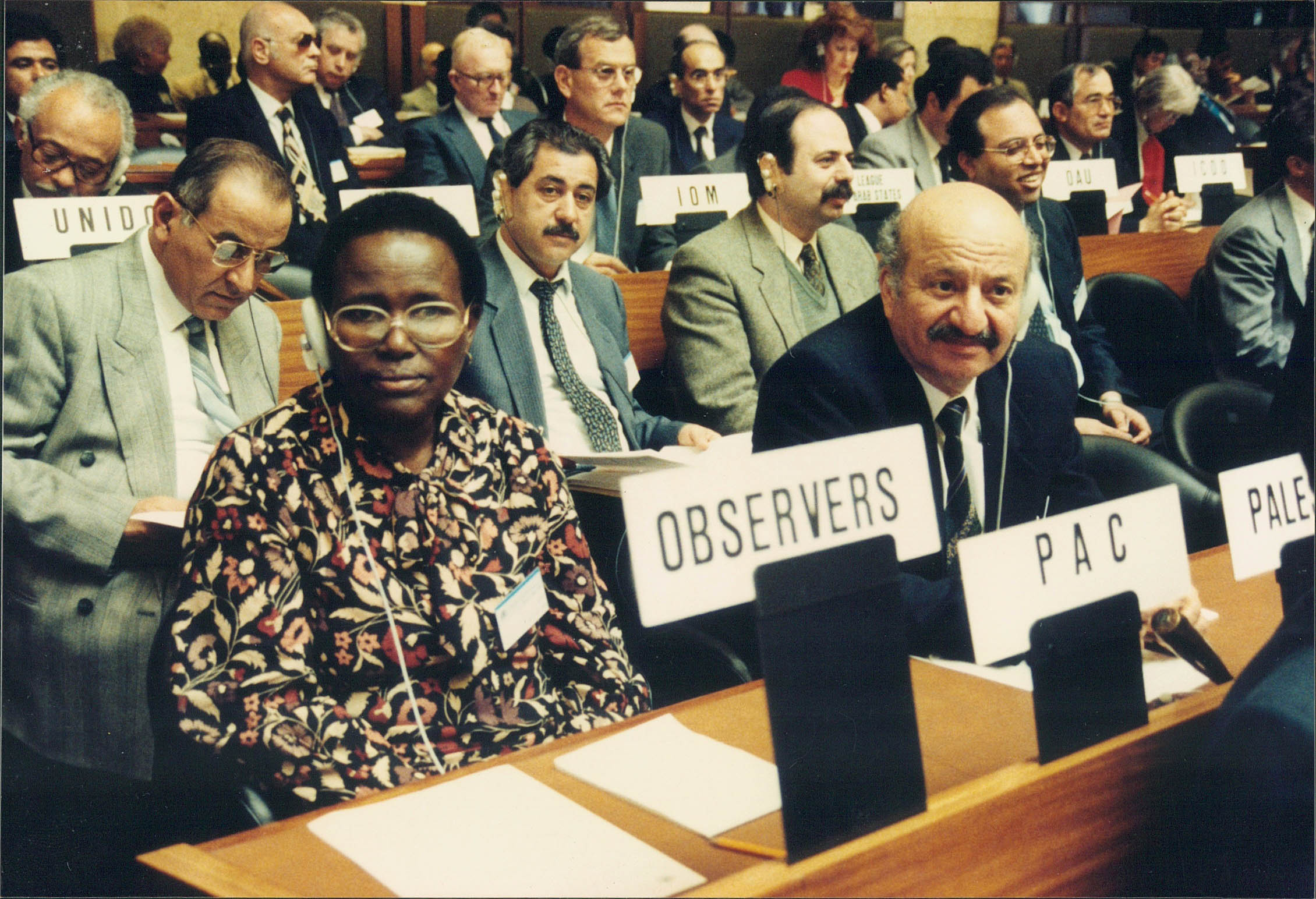

[Watching: The PAC had observer status in the United Nations’ General Assembly. Nomvo Booi was a member of the PAC’s central committee as secretary for welfare]

When the PAC was outlawed by the government in 1960, Booi joined the armed struggle as the regional secretary of the PAC in the then Transkei. Following the Sharpeville Massacre on March 21 that year, a state of emergency was declared by the apartheid regime.

In the same year, 24-year-old Booi began to work for Poqo, the PAC’s military wing, which later became the Azanian People’s Liberation Army (Apla), while also coming to terms with motherhood. She was seen as a mother figure of the wing and endearingly referred to as Poqokazi. She worked under Nzimeni Elliot Mfaxa and the chairperson of the PAC, John Nyathi Pokela, in the Eastern Cape region.

At the age of 26, she was arrested during a midnight raid in Ngcobo for being in possession of a letter from a friend in exile.

“I was constantly moved between prisons, got no medical attention and at times got no food. The moves were designed to disorientate and isolate me from friends and family. None of the members of my family were allowed to visit and were often turned away at the prison gates by officers who claimed to have no knowledge of my whereabouts,” Booi wrote in a typed letter, which appears in an autobiography. This initial detention lasted 10 months.

Subsequently, she was charged under the Suppression of Communism Act and given a three-year sentence. For the five years that she was imprisoned, she served time in Barberton, Nylstromand Kroonstad.

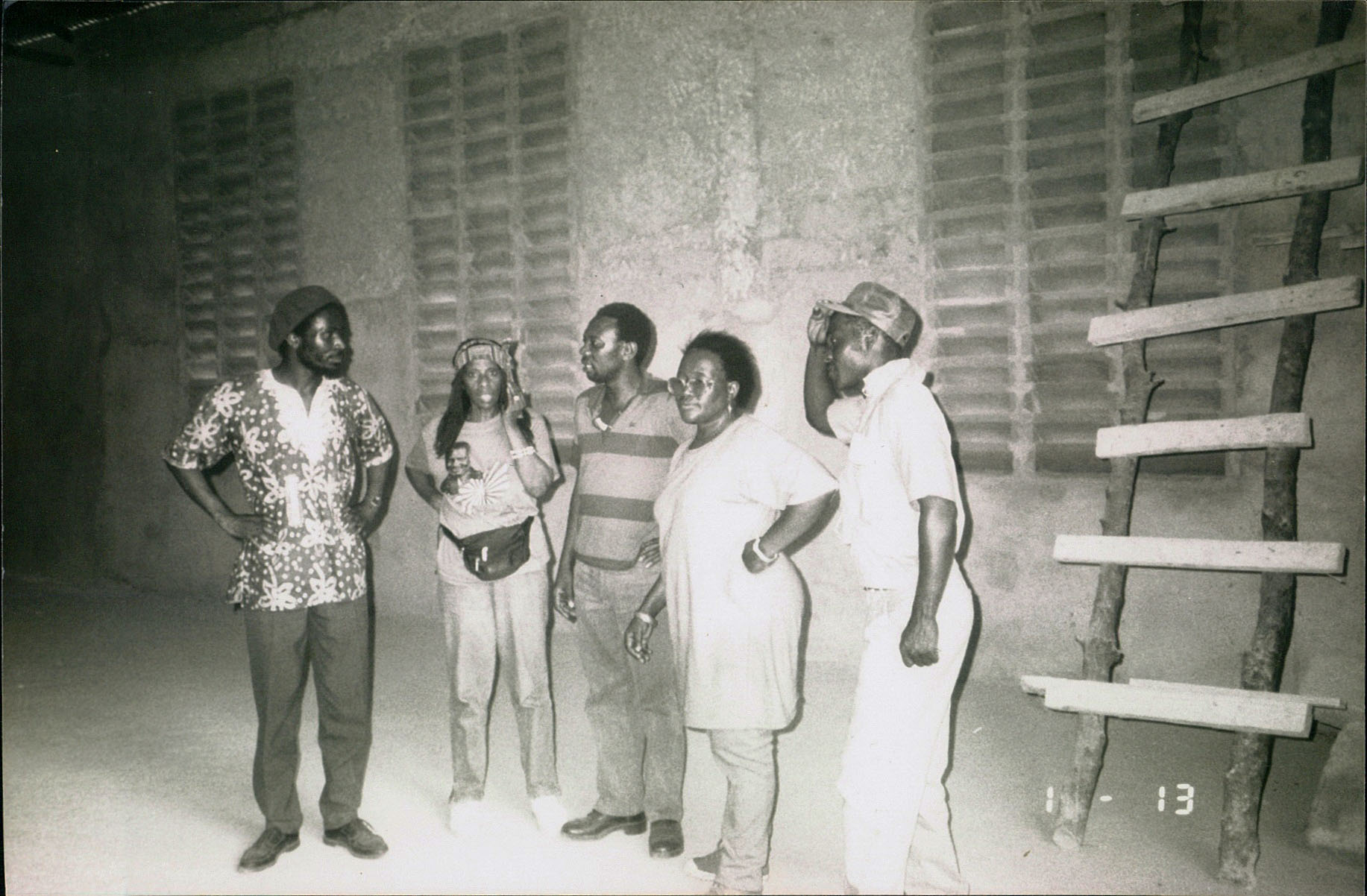

[Nomvo Booi at a shooting range with her fellow cadres in Tanzania while they were exiled]

Not long after her release, she left South Africa to continue the fight for freedom. She first moved to Lesotho and was later sent to Tanzania and then Zimbabwe to work for the PAC’s mission in exile. She received military training and took on a number of responsibilities.

Because of her dedication to the liberation movement, Booi had to make sacrifices.

One of them was not spending enough time with her three daughters, Khanyisa, Mpho and Sibongile. Her eldest daughter stayed in eGcuwa with her family and the other two followed their mother into exile, where they lived with another South African family.

“Before we left South Africa, I had sat my children down and told them that, at 16 and 14, they were grown up and I needed them to allow me to fight my cause and indirectly fight for their future. I told them that I had taught them everything that they needed to know to be upstanding young adults and that they should continue to abide by my teachings.”

[A picture taken by Sibongile Booi, one of Nomvo Booi’s daughters in 1991]

PAC veteran Vuma Ntikinca, who joined liberation cadres in Lesotho and knew Mam’Booi recalls meeting her. “I met her in 1979 when I was in exile eLesotho. By that time, we knew her as a very active woman. She was acting as an underground courier for the military wing of the PAC. That was very dangerous indeed! Oh! She was a very brave woman. She would literally carry weapons from Lesotho and infiltrate those weapons into South Africa, crossing the borders illegally and setting up the dead letter boxes inside the country for the soldiers to have access to weapons so they could continue to fight.

[Team work: Nomvo Booi also received training at Mgagao military camp in Iringa, Tanzania]

“Among the most dangerous roles she had to play, as an intelligence operative of Apla, was to harbour a trained terrorist. Do you know how dangerous it was to harbour a trained so-called terrorist then? That is Mam’Nomvo. Very brave woman,” he says with pride.

Those who were a part of the exiled community, like Ntikinca, revered her because, in addition to playing a militant role, she was a mother figure and attended to their everyday needs. While she was in Tanzania, this role was solidified when she was assigned the role of secretary for health and social welfare. She had to ensure that the soldiers were well taken care of with regard to medical treatment, food supply and mediation with their families in South Africa.

“UMam’Nomvo was so loved in the camp there, she was like umama. She was so caring, she would take a case from the beginning to the end. She would try to mend broken marriages and acted as a social worker. She did this in collaboration with the arms and the commissariat sections of Apla,” recalls Ntikinca, who has since returned to the Eastern Cape.

Her eyes were always sharp and unafraid behind her stylish hexagon-shaped prescription glasses, which she needed for handwork. With the same hands that she used to sew wedding dresses for the likes of then Transkei leader Kaiser Matanzima’s wife and the rest of the Thembu royal family, she could assemble a semi-automatic rifle.

[Comrades: Nomvo Booi, in her stylish hexagon shaped glasses, with Comrade Mzothane and Comrade Sipho Matolweni, at one of the many houses owned by the PAC in Dar es Salaam]

“The biggest task that I had to perform was that of unveiling the tombstone of the late founding president of the PAC, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe, who died in 1978,” writes Booi.

She was part of the covert organising committee and did most of the work outside the country.

“Unknown to the authorities, we organised a well-attended unveiling ceremony in Graaff-Reinet in 1981, well befitting the respect we felt for Robert Sobukwe,” she adds.

Many may not know her because, during this time, women in the armed struggle were seen but seldom heard outside the immediate environment in which they worked, where they were not auxiliaries but necessities. Cadres and operatives like Booi, who played a significant role, were not mentioned in news reports.

Those who knew her personally say she did not mind this because her dedication came from a need to restore the dignity of African people; she had no desire to be praised in news reports. And when she was photographed — whether in her military fatigues, a dashiki or the blue safari two-piece she is seen wearing at a PAC camp in exile — her work was always on the ground.

[Nomvo Booi in her fatigues at the Bamagamoyo camp at Mothopheng Military College in Tanzania]

She returned to South Africa in 1992 following the unbanning of political organisations in 1990 to be a part of the negotiations for a new South Africa. She was pleased to be back. “For all the toil, sweat and pains over the years, I felt vindicated. The struggle and sacrifice had not been in vain.”

Subsequent to experiencing memory loss, she suffered a stroke in 2009. After seven years of poor health, she died at home in East London where she received a burial from Apla forces on May 7 2016.

“Even though I have now been silenced by a stroke that affected my speech in 2009, I have throughout my adult life been very outspoken and never minced my words. One trait that remains in my old age is the stubbornness I displayed in my early life. Once I resolve that an action is justified, nothing else will sway my mind.”

All comments by Mam’Nomvo Booi are from a short autobiography written in 2011 with the help of her daughters Mpho and Sibongile