Gideon Makatus fathers property in Alex was taken from him in 1973. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Lydia Shadi Nhlapo’s mother was resting under a tree on her property in Second Avenue in Alexandra when she was rudely interrupted by an employee from the Johannesburg City Council.

“Jy sit lekker hier onder die skadu, ne?” the council employee remarked. (You’re sitting nicely in the shade, eh?)

“Dis my plek mos, ek moet lekker sit,” Nhlapo’s mother fired back in response. (This is my place, I can rest nicely.)

“Kyk hier so, ou vrou. Jou plek is net hier bo. Hier onder is onse grond,” said the council employee. (Look here, old woman. Your place is just here on top. Here underneath is our land.)

The cocky council employee had come to deliver devastating news that would ruin the family and those of more than 2 000 other Alexandra landowners. That day, in the early 1970s, the family became tenants on the land they had bought with the proceeds from their toil.

They became victims of a sustained 25-year reign of terror in which the government dispossessed Alexandra’s residents of their title deeds and expropriated properties, offering minimal financial compensation, which was nowhere near market related.

Alexandra, established in 1912, was one of the few places where black people could own land under the white minority Union of South Africa government between 1910 and 1948.

But after coming to power in 1948, the National Party government began to dismantle black people’s land rights, especially in urban areas.

Freehold rights in areas such as Lady Selborne in Pretoria and Sophiatown in Johannesburg were targeted. Homes were razed and residents who were once landowners were sent off to far-off townships they did not love, to live as tenants of a state they hated and never voted for.

In 1968, the long, brutal arm of the apartheid state reached Alexandra. Families who had bought plots and built homes and businesses found themselves reduced to being tenants. The onslaught continued until 1984 when all of Alex’s property owners were stripped of their title deeds.

Activists say, during that period, at least one-third of Alexandra was demolished to make way for the building of schools, hostels and other facilities. Residents who were forcibly removed were sent to areas such as Soweto and Tembisa.

Heartbroken

Gideon Makatu’s father died of a heart attack in 1974, a year after the expropriation of his property on which he had built a house, a store and three outbuildings. The family was paid a paltry R1 300 as compensation.

From having lived in a big house and owning land, the Makatu family of six was forced to go to live in a single room in 13th Avenue.

“Imagine the guy who has worked so hard and bought his property and one day he wakes up and … haak! No wonder he suffered a heart attack. It was pathetic,” says Makatu.

Makatu bought a house in the suburb of Kelvin in the early 1990s when state-sponsored violence was at its height. But he says he only goes to Kelvin to sleep and spends most of his time in Alexandra, with lifelong friends such as Mothibi Segopa.

They spend their days in the offices of the Alexandra Land and Property Owners’ Association (Alpoa), located in one of the oldest buildings in the township in Second Avenue.

Segopa recalls that, in the decades before the apartheid onslaught on the township gained momentum, the building (which is now dilapidated) was used to hold the bicycles and dogs of owners who had failed to pay their taxes. Then, the property owners ran the affairs of the township, collecting rates and taxes and upholding law and order.

In the past 20 years, Alpoa has been fighting to help Alexandra property owners and their descendants to have their title deeds restored to them.

As part of the Restitution of Land Rights Act (1994), 1 578 Alexandra residents have lodged land claims with the Commission of Restitution of Land Rights.

But theirs has been a long wait and their struggle has resulted in a protracted court battle. In June 2005, Alpoa, the Alexandra Property Owners’ Rights groups and the South African National Civics Organisation took the Gauteng department of human settlements, the City of Johannesburg and the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights to court. They successfully interdicted the government and the city from going ahead with infrastructure development projects in the old part of the township before restoring title deeds to the property owners.

In August 2008, the government lost a court bid to annul the interdict and, in 2016, the parties eventually signed a statement of intent after six years of negotiations that started in May 2010.

The city said, as part of the agreement, each claimant would “be provided with a solution equivalent to the monetary compensation that might be payable in respect of the property concerned”. It also said the monetary compensation would be based on a proper land valuation process in accordance with applicable government policy. The agreement offered each claimant four options: the provision of title deeds for stands in Alexandra; the provision of alternative stands; participation in a planned redevelopment of Alexandra; or financial compensation. The city, then under the ANC, estimated the monetary compensation to all 2 538 property owners at between R1.8-billion and R2-billion, assuming all of them opted for financial compensation.

But two weeks ago, Alpoa members marched on the ANC’s Luthuli House headquarters in Johannesburg to voice their frustration about the lack of action since the signing of the agreement two years ago.

This year, protesters marched on Luthuli House about the lack of action. (Lucky Morajane/Gallo Images/Daily Sun)

Segopa says Gauteng MEC for human settlements Uhuru Moiloa met representatives of the affected parties after the protest and has promised to convene another meeting in a bid to resolve the matter.

The department’s spokesperson, Keith Khoza, says Moiloa is waiting for responses from Alpoa and other organisations. He says they met last week and resolved that the organisations would convene with their members and make comments on the protocol that had been signed.

“We agreed that all landowners would make representations to the Alexandra Land Task team, which is made up of the three organisations and they would get back to the department and we would take it from there,” he says.

Segopa blames, among other things, the Cabinet reshuffles in the provincial government for the delay in settling the matter. Each of the eight past MECs has promised to look into the matter, only to be removed thereafter.

Waiting for dignity

But the long wait is weighing heavily on elders like Nhlapo. The frail octogenarian, who still lives on the property where she was raised, is worried she might not live to see

the day when her dignity and that of her parents is finally restored.

She sometimes looks up at the framed photograph of her parents hanging on the walls and says a silent prayer, pleading for their intervention before her time is up.

The Nhlapo property comprises a large main house, a thatched chalet and another outbuilding, all neatly painted in dark green with a paved driveway. It is unlike many of the township’s plots, which are overcrowded with shacks and outbuildings surrounding the main houses. The family has never had tenants.

Photographs (above) of Lydia Shadi Nhlapho’s (below) parents hang in the home taken from them in the 1970s. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Property owners in Alex rented out space in their large yards to make extra income and also in response to the dire shortage of housing for people migrating to the city. But after property owners were dispossessed of their title deeds, tenants stopped paying rent and properties gradually degenerated into slums.

“You can’t even see the original houses [from the street] anymore,” says Tony Mothibi, a member of Alpoa, who was born and has lived in Alex all his 66 years.

One downside of the disempowerment of property owners was the loss of control and regulation of tenants. Many who are third- and fourth- generation Alexandrans feel entitled to the structures where their grandparents and parents lived as tenants decades ago.

Mothibi says one of the biggest challenges facing the township is the lack of by-law enforcement, which has resulted in illegal structures, including double-storey homes and businesses, being erected by tenants on properties they don’t own.

Some tenants have even become landlords themselves, building large structures, which they rent out. This has resulted in further overcrowding and has placed a burden on the township’s old infrastructure.

“Property owners are powerless. They can’t do anything because they don’t have title deeds. The tenants are just building and they know no one will do anything,” Mothibi says.

Overcrowding

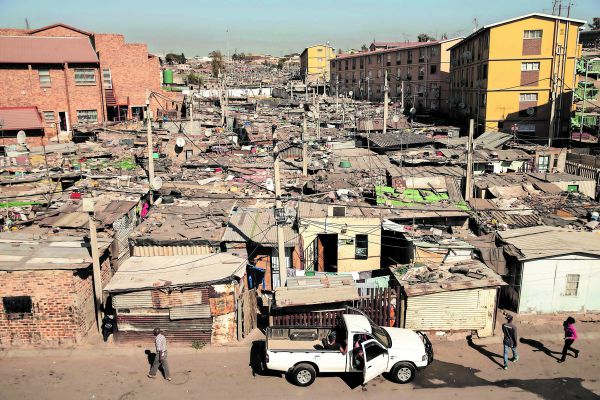

Along the narrow, crowded paved streets, shacks and brick structures of different kinds cling dangerously to the crumbling pavements. Endless streams of people — men and women on their way from doing errands or going to work, children chasing footballs, mechanics fixing cars, taxis and hawkers peddling their wares — battle for space along the streets where trickles of dirty water flow down from the alleyways.

The rusted roofs of the old Alex homes built by the original property owners stand like relics of history, crowded in by shacks and houses.

Grand Tuscan-style double-storeys tower above the confusion. They resemble South American favelas, a sign of a new Alexandra battling to rise and obliterate the aged slum.

The 2011 Census by Statistics South Africa put Alexandra’s population at 179 624, with 74.3% of homes as formal dwellings and a population density of 25 979 persons a square kilometre. Alexandra covers only eight square kilometres. The fact that it’s locked in by four other suburbs has made it impossible for the township to expand.

A 2016 agreement to restore title deeds to Alexandra residents, taken from them during apartheid, has not yet been honoured. People erected shacks on these properties, crowding in on the original houses, and now the grand- and great-grand-children of these tenants also want title deeds. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Image)

This has created a hunger for land, especially among young people like Tshepo Moeng and his friend, Japie Mogotsi. The pair run the iKasi Gym from the backyard of their crowded home in Seventh Avenue, not far from John Madzeka Xhoma’s home, where a young Nelson Mandela lived as a tenant during his student days in the 1940s.

The gym, which has more than 300 members, received a donation of equipment from businessperson Richard Branson, largely because of its unique location in an urban slum.

But both Tshepo and Mogotsi want more land, which would

improve conditions for their clients, who have to work out in crammed conditions.

Mogotsi says the overcrowding has exposed children to many vices, including alcohol, drugs and crime. He doesn’t want his own children to grow up in Alex and wishes the land issue would be resolved.

But it is not just people like them. Others like Nhlapo pray for a quick end to the long, dragged-out saga and to have their title deeds restored.

“I don’t want to leave this world not having got my title deed. I want to leave my grandchildren with something,” she says. — Mukurukuru Media