Planting thought: Swiss artist Uriel Orlow questions the naming of plants which, despite being indigenous to South Africa, have European monikers. His exhibition uses film, sound, photography and video installation to explore this colonial phenomenon

“I was here on a short research trip,” says Orlow inside POOL on Voorhout Street in Doornfontein, Johannesburg, explaining the genesis of a work more than three years in the making.

“I went to the Mayibuye Archives in Cape Town and to the South African History Archive here. I happened to meet somebody for coffee in the café of the botanical gardens in Kirstenbosch. As I walked through, I noticed the labels of the plants and how most of the plant labels are in English or in Latin.

“It struck me that in South Africa, where there are 11 official languages, and even more that are not official, what does it mean to have English and Latin as the names of the plants in the botanical gardens? It’s connected to the whole colonial history and it’s connected to all these other things that I had been looking at in the archives. It’s like a prehistory of that.”

Orlow’s project, at least aspects of it, highlight the far-reaching act of naming as taking ownership. One of the sound installations that make up Theatrum Botanicum is called What Plants Were Called Before They Had Names. Its title points to the irony of naming things already named, and its form points to the prevailing conditions that allowed this practice to thrive.

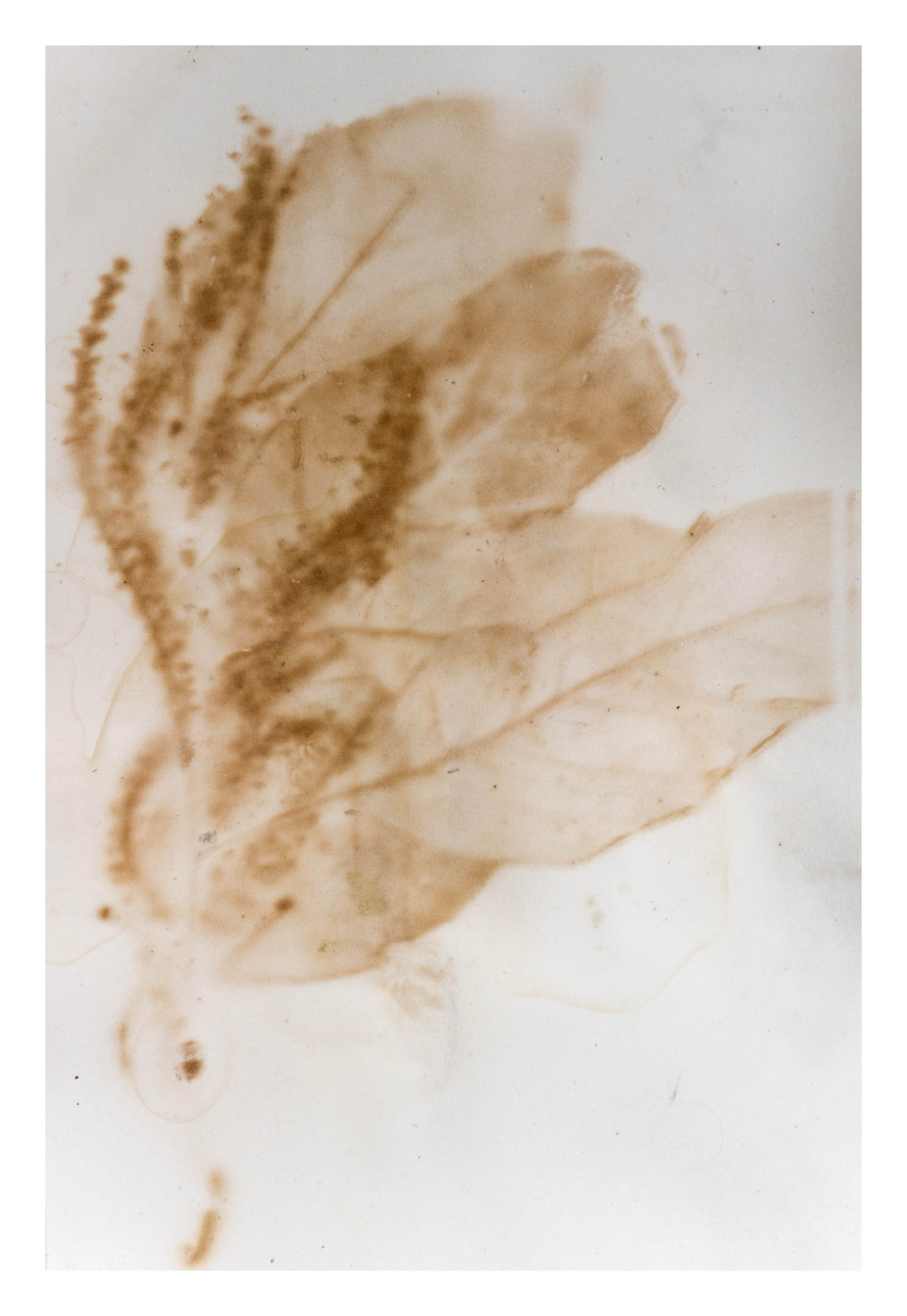

Combining projected images from overhead projectors, titled Echo, with the audio of plant names emitted from suspended, undraped speakers, the names echo but also demand that one must get close to a speaker for an intimate acknowledgement of other names.

[Imprinted: Uriel Orlow’s Echo (#3), 2017, is one of a series of eight images projected through overhead projectors]

“One of the first things I wanted to do was to explore why it was so easy to disregard existing plant knowledge and names,” says Orlow. “It is because it was oral knowledge. So it was much more ephemeral.

“So I started meeting people and started to record plant names. So the piece is basically an audio dictionary of plant names in about a dozen South African languages. It’s almost kind of, I don’t want to say rectifying this thing, but it is kind of engaging with it.”

Orlow stops himself a lot during our conversation. He does this to ponder the right word before speaking it, to pull out facts from the mental files that constitute what is an exhaustive body of work.And there are more symbolic stops to seemingly ponder how his own position guided his approach at different turns in assembling the work.

A large, grainy postcard-scene wallpaper of what looks like a river or waterway in Zurich (where Orlow was born) seems to provide our next segue. Red “geraniums” pepper the scene, especially in arrangements around a foregrounded bridge.

“Switzerland is full of red geraniums,” explains Orlow. “In Zurich, you see them all over the city. You see them on balconies, in the aisles. They are almost considered a national symbol. But what you discover is that they come from the Cape. They were brought by the Dutch East India Company because there was big hunger in the horticultural industry. All the aristocrats wanted new exotic plants.”

Only, the plants were not geraniums, which are apparently biologically incapable of being red. Misidentified for more than a century, the Swiss have never bothered to correct the name to pelargonium, a fact that still leaves out what the other populations of the Cape called them.

Orlow’s collaborative work, which includes a book with essays and book-form representations of the exhibited work, brings up not only flora but characters not popularly known in South Africa’s historical cannon. Among these is Mafavuke Ngcobo, who inspired two short films in the exhibition, one of them titled The Crown Against Mafavuke, a restaging of his 1940 trial, which centred on the illegality of mixing of Western and indigenous medicine.

“Mafavuke’s story is about the economic power of plants,” says Orlow. “There were laws about what pharmacists could do and what traditional healers could do, because izinyanga [healers] were very much controlled; they had to have a licence. Without a pharmacist licence, you weren’t able to use Western medicine.

“He was accused of using these ingredients, but underneath that there was a kind of ideological and professional competition, because he started a mail-order business. He was savvy and even white people started buying muthi from him. The white pharmacists got scared that he was taking their business, and this is why they mounted this trial.”

For the film, Orlow restages the trial with significant differences. For one, Mafavuke speaks to the audience in the trial, as if forcing us to bear witness. In the original trial, he did not speak.

In the staging of this 20-minute film, the actors change roles, switching gender and ethnicity. There is an additional accompanying video in which Mafavuke, as if turning in his grave at the current status quo, sets up a tribunal to question the rise of bioprospecting by pharmaceuticals in South Africa.

There is also a photographic exhibition at the Market Photo Workshop titled The Memory of Trees, an installation that portrays trees as witnesses and holders of history. And, there is a video installation in collaboration with Lindiwe Matshikiza titled The Fairest Heritage, in which she places herself, in various costumes, in front of projected images of the archive photographs of the 50th anniversary of the Kirstenbosch botanical gardens, celebrated in 1963 in Cape Town.

[Lindiwe Matshikiza places herself in front of projected images of the archive photographs of the 50th anniversary of the Kirstenbosch botanical gardens, in 1963 in Cape Town.]

One may well ask why a work of this magnitude and importance had to be sparked by a Swiss artist, who stumbled on it while on a coffee break in the Kirstenbosch gardens.

It’s a question Russell Hlongwane, a researcher for the Durban leg of the project, which kicks off on September 14, was confronted with as well when he visited Professor Kaya Hassan at the Indigenous Knowledge Systems school based at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN).

It was a difficult question for Hlongwane to contend with but one that, thinking of it now, makes him reflect on his own ethics and Orlow’s practice.

“I have never engaged with this area of practice and it is difficult to enter,” says Hlongwane. “The way Uriel has set it up was to provide easy access into this area of practice without dumbing the material down.

“The main proponent of the research into this field in Durban was Mkhuluwe “Zihlahla zemithi” Cele.I didn’t know about his practice, but he was a central figure in the preservation and the advocacy and lobbying of traditional healers in KwaZulu-Natal, during apartheid and post-apartheid, leading up to his passing. What he had set up —I think it’s unfortunate that it’s not in the public imagination.

“But then to also see how he had started making inroads into the academy, the University of Durban-Westville [now part of UKZN] had an indigenous knowledge systems department. He had started locating his work in different areas and different spheres, and they are interacting with this area of indigenous knowledge practices.”

A spin off for Hlongwane is that he will collaborate further with the centre after this project is over, giving Theatrium Botanicum even more legs than it could have imagined.

Theatrum Botanicum opens in Johannesburg at POOL, 23 Voorhout Street, until November 3, at Cape Town’s ICA Live Art Festival on September 11 and 12 and at Durban Art Gallery from September 14 to October 28