Doing deals: Chinas President Xi Jinping and President Cyril Ramaphosa met at the Forum on China-Africa Co-operation earlier this month. (Lintao Zhang/AFP)

President Cyril Ramaphosa assured South Africans this week that the government was not in the habit of “handing over the assets of our country to other nations [or] to other entities outside of our country”.

The state “has not sold the soul of South Africa to the highest bidder”, he promised, in reply to a question in the National Council of Provinces about the details of a R33-billion loan from the China Development Bank (CDB) to embattled power utility Eskom.

Ramaphosa’s reply is of particular significance following a report by Africa Confidential last week that Zambia’s state electricity company, Zesco, is in talks about a takeover by a Chinese company. This has fuelled the debate about China’s supposed “debt-trap diplomacy” — that it is angling to take over the strategic assets of nations that fail to repay their debts, thereby increasing its geopolitical influence.

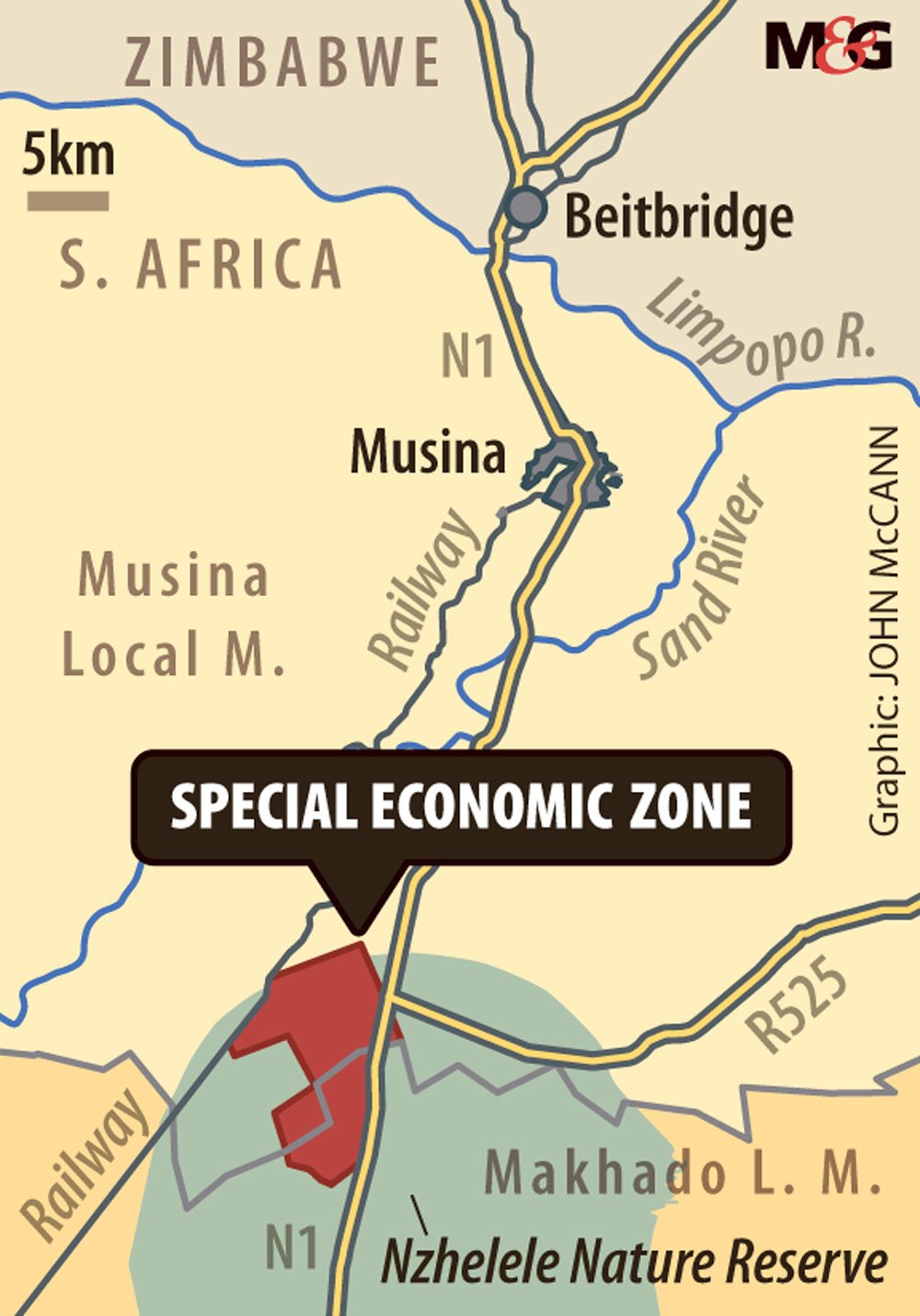

Questions have also been raised on social media about whether a Chinese-developed special economic zone (SEZ) in Limpopo, which has been in the works since 2014, is a sign of South Africa surrendering its sovereignty to China. The investment, which is expected to hit R130-billion, will include its own power station.

But the department of trade and industry said the South African energy and metallurgical cluster, as it is known, which falls under the Musina-Makhado SEZ, is intended to create 21 000 direct jobs and provide skills and training opportunities for people, particularly the youth, in the area.

The zone was gazetted in 2016 and last year an operator agreement was signed between the Musina-Makhado SEZ state-owned company (SOC) and the Shenzhen Hoimor Resources Holding Company Limited.

Shenzhen Hoimor Resources, which is also an anchor investor, will “develop, operate and manage” the cluster, the department said at the time. The complex will include a power station as well as coking, ferrochrome, pig iron, steel, stainless steel and lime plants, and supporting facilities. The goods manufactured in the SEZ will be for domestic and export markets, it said.

“Only under exceptional circumstances where certain skills are not available in the country will Chinese expatriates be allowed to provide the scarce skills, training of locals and skills transfer,” the department said. “The Musina-Makhado SOC has been established to ensure that this is done in line with applicable legislation.”

According to the department, the project will be rolled out over 10 to 15 years and is expected to generate an investment of about R130-billion at the current dollar/rand exchange rate.

Misgivings about South Africa’s deepening financial ties to China come against a backdrop of concern about China’s growing influence on the continent and in other parts of the world, particularly by Western powers. But China-Africa experts have cautioned that the debt-trap diplomacy narrative does not reflect the complexity of the relationship between the Asian giant and individual African nations.

Zambia’s minister of information and broadcasting services and chief government spokesperson, Dora Siliya, said in a tweet that all stories regarding a takeover by, or a sale of public assets to, China are false.

But Zambia would not be the first country to give up a key national asset to China in the face of mounting debt. Sri Lanka reportedly ceded the port of Hambantota to China in December after it could not repay its loans for the development of the project. Other countries such as Djibouti are confronting a similar dilemma as its debt to China far outstrips its ability to pay it.

According to Cobus van Staden, a senior researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs, although Africa’s debt has been increasing rapidly, and China is becoming an important lender on the continent, it is not the only one. China’s share of Africa’s debt is significant but it is not the largest, he says.

“Quite a lot of the remaining debt is to Western countries and particularly Western private lenders,” he says, adding that this detail “is frequently left out of the debt-trap discourse”.

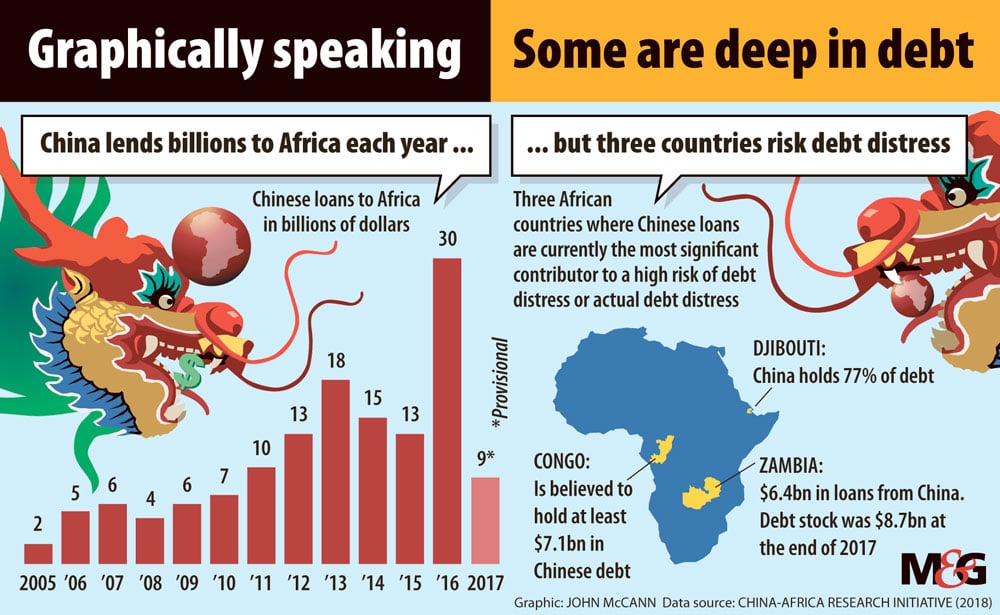

In an August briefing paper by the China-Africa Research Initiative, at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, researchers say that although many countries in Africa have borrowed heavily from China and from other sources, Chinese loans are “not currently a major contributor to debt distress in Africa”.

Only in three countries — Zambia, Djibouti and the Congo (Brazzaville) — are Chinese loans “the most significant contributor to high risk of actual debt distress”.

According to the paper, Zambia’s debt stock was $8.7-billion at the end of last year, of which at least $6.4-billion had been borrowed from Chinese lenders.

At the end of 2016, Chinese financiers held 77% of Djibouti’s debt, the researchers say, while in the Congo “the debt situation is so unclear even to the International Monetary Fundthat the president visited Beijing in July 2018 to ascertain just what they owed”. The researchers estimate the Congo holds at least $7.1-billion in Chinese debt.

In many other African nations deemed to be at risk of being in debt distress or are already debt distressed, the researchers found that China’s share of their debt, though not insignificant, is not necessarily the problem. For instance, Mozambique had a debt of $10-billion, with China’s share being about $2.3-billion. China holds 23% of Zimbabwe’s external debt, and the remaining 77% is held by the Paris Club — 19 countries that include some in Western Europe, Britain, Scandinavian countries, the United States and Japan — and other multilateral agencies.

Ross Anthony, the director of Stellenbosch University’s Centre for Chinese Studies, says the debt-trap narrative fits into a Euro-American discourse, and this grouping is very anxious about China’s ramped-up “going out” strategy — its policy of encouraging Chinese firms to invest globally.

But some Chinese-funded projects are more risky than those in other countries, he says, Djibouti being a good example.

Certain developing countries are re-considering Chinese loans, such as Pakistan and Malaysia, Anthony says. Malaysia recently announced it was cancelling a $20-billion rail project, according to The Economist. Meanwhile, The Washington Post has reported that Pakistan is believed to be reconsidering the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a $62-billion project, which includes port expansions, highways and power plants.

Van Staden says China’s actions on the African continent are too often painted as that of a “single actor”. But the Chinese government’s involvement is often complicated by the role of one or several Chinese companies in different countries, which have their own business agendas, he says.

When it comes to the question of whether South Africa has signed itself up for possible debt trap through the likes of the Eskom deal will depend on the terms of the agreement, says Anthony.

Ramaphosa told Parliament the terms of the Eskom loan could not be divulged because it would put the utility at a commercial disadvantage when negotiating in the market. He said there were no specific conditions for this loan, guaranteed by the government. No Eskom assets had been used as security for the loan and the China Development Bank was not “entitled to any direct or indirect ownership of Eskom assets”.

Ramaphosa also did not divulge details of a R4-billion loan to parastatal Transnet by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China but, he said, it came with “terms and conditions that are standard for this type of loan”.

Anthony says hopefully, the government will make the Eskom deal available for scrutiny, given the strategic sector of the investment and that taxpayers will foot the bill.

If — and this is not necessarily the case — it turns out that the deal is not sustainable, the lion’s share of the blame must be put at the feet of the South African side, Anthony says, because “they are the ones who signed the agreement”.