Undercover: Bhekisisa reporter Pontsho Pilane posed as a pregnant woman considering an abortion at the Amato Centre in Pretoria to learn about the pregnancy counselling it offers. (Oupa Nkosi)

Lerato Molefe stares blankly at the sign erected in the yard in front of her. Her eyes are fixed on the blue silhouette drawing of two women with bulging bellies.

“FREE pregnancy test” … “Information on OPTIONS”, the sign reads.

She’s parked in front of the Amato Pregnancy Counselling Centre in Arcadia, Pretoria.

A short, elderly woman exits the house in the yard. Her name is Mariska Verster*. She is a counsellor and helps to manage the centre.

Molefe gets out of her car and slowly approaches the gate. This will be the first time she and Verster meet in person. They’ve only spoken on the phone.

Molefe (26) stretches her hand out to greet the old woman. Instead, Verster welcomes her with a hug.

“God wants you to be here,” Verster reassures her. “Nobody comes here unless it was divinely appointed by God.”

Molefe is about two months pregnant. She came to Verster for counselling before deciding whether to terminate the pregnancy or carry full term. But she is leaning towards abortion.

The pair make their way inside the house. They sit on chairs placed across from each other in what looks like a study room turned into an office.

“What is happening in your heart when you think about this pregnancy?”

“I’m not sure if I want to be a mother. I don’t know if I’ll have a job next year and I’m just also worried about the finances,” Molefe says.

Verster picks up a pregnancy wheel — a small calendar that uses your last menstrual period to help determine your due date — from the table next to her. “Nine weeks pregnant … which means this baby should come around the 25th of March [next year],” she explains.

But Lerato Molefe is not real.

Lerato Molefe is me.

A quiet murmur passes through the University of Pretoria’s (UP) main campus in Hatfield. Small groups of students are scattered around the university grounds as many have retreated into libraries to study for their mid-year exams. The white walls of the female toilets in the Huis-en-Haard Building are plastered with a poster: “Pregnant, alone and confused? It’s good to know there’s someone to talk to.”

A female student says: “These posters are everywhere — even in the campus clinic.” They belong to Verster’s organisation, Amato, which, in the organisation’s own words, “counsels vulnerable women that find themselves in a pregnancy crisis” around Pretoria.

The nongovernmental organisation (NGO) has been operating since 2011, says Verster. According to its website, Amato has helped almost 400 clients in the past year.

Amato also has a counselling room on UP’s main campus. Verster explains: “We are open thrice a week on main campus — on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays. On Wednesdays, we’re at the Mamelodi and Groenkloof campuses and on Thursdays at the medical school campus. If Onderstepoort needs us, we’ll go there.”

A UP staff member and a student, who spoke to Bhekisisa anonymously, say the campus clinic health workers refer pregnant students considering terminating their pregnancies to Amato’s on-campus offices. The NGO has a counselling room in the Roosmaryn Building, opposite the university’s health facility.

“The [university] clinic is not equipped to perform terminations, so pregnant students are referred to Amato when they are confused or want an abortion,” the staff member says. “We’ve asked university management why an organisation that’s clearly against abortion is allowed to operate [as the main provider of abortion counselling] on campus, but we’ve not gotten any answers.”

UP confirmed to Bhekisisa that Amato “provides support to students” at the university. “Amato’s services are not compulsory; students have a choice and are referred to Amato and/or the student counselling unit for counselling if they’re not yet sure how to respond to an unplanned pregnancy and would like to talk through the options that are available to them,” says UP’s director of university relations, Rikus Delport.

When asked about the concerns raised by students and staff members about Amato’s counselling, Delport says the university “will continue to make every effort to ensure that students receive meaningful and quality services when they need them”.

The NGO is also involved at Tshwane University of Technology (TUT) and at Boston College’s Arcadia campus, says Verster. TUT’s media liaison officer did not respond to Bhekisisa’s repeated requests for comment. Boston College distanced itself from having any formal relationship with the centre. “We don’t make use of the Amato pregnancy centre’s services as Boston employs a full-time qualified counsellor to assist with student-related issues. We [have] previously invited them — along with many other organisations — to attend our awareness campaign on site,” says Taryn Steenkamp, branch manager of Boston’s Arcadia campus.

Verster says Amato is sometimes invited to speak to learners in public schools around Pretoria. It operates independently but falls under an umbrella organisation called Africa Cares for Life — a network of over 70 crisis pregnancy centres in Southern Africa, according to an Amato information booklet.

A 2016 study by the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada defines crisis pregnancy centres as “anti-choice agencies that present themselves as unbiased medical clinics or counselling centres” mostly run by Christian organisations that generally refuse to refer clients to abortion services or contraception, and “promote misinformation”.

Most of the centres in the United States belong to one of two national evangelical organisations, according to a 2014 study published in the Social Science & Medicine journal. Information about the funding models for such centres in South Africa is scarce, although some experts believe right-wing Christian organisations in the US play a role.

Use the search tool to find a safe, free abortion closest to you. Do you spot an error? Let us know. Please note that this map is based on facilities’ self reporting so it’s best to call ahead and confirm services are offered.

I decided to go undercover in order to experience Amato’s counselling first hand. During the session, as Lerato, I also told Verster that I had an abortion when I was 17, and requested post-abortion counselling from Amato, in addition to asking advice about my current pregnancy.

“God has put something in here,” says Verster as she presses on her chest with the palm of her hands. “It’s called a mommy heart, and it says: ‘I need to love. I need to care. I need to nourish.’”

The hormones that are “induced during pregnancy create an emotional bond between the pregnant woman and her baby”, she tells me. And having an abortion “pushes this mommy feeling down”.

Verster adjusts her spectacles and touches her pearl necklace. She asks: “Did you have any emotional effects [after your abortion]?”

I respond: “I felt guilty about keeping the secret from my parents and sometimes I wonder what life would have been like had I had the baby.”

Having an abortion causes a lot of negative emotions and often leads to relationship problems, Verster continues. She explains: “Post-abortion counselling helps a woman get to a place where she can say: ‘I’ve lost my baby. I know this was a baby and that the baby is with God, and I need to recognise what was my responsibility.’”

Experts reviewed almost two decades of research into abortions and mental health as part of a 2009 Harvard Review of Psychiatry study. They found no convincing evidence that terminating a pregnancy was associated with any mental health risk. They also said very few studies looked at what else in a woman’s life could influence her feelings after a termination.

To try to answer this, a 2016 study in the British Medical Journal interviewed almost 900 women over four years who had sought out or obtained an abortion. They found that more than a third had at least one symptom of the mental health condition known as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) before they got pregnant. People who experience horrific events can develop flashbacks, nightmares and anxiety as part of PTSD. For most women in the sample, their PTSD was linked to sexual, physical or emotional abuse.

Only 2% of women who eventually terminated their pregnancies during the study said they had PTSD symptoms tied to the abortion — twice as many women attributed their PTSD to intimate partner violence even after seeking out abortions. One in five said their stress was caused by relationship problems that didn’t involve violence.

Verster warns that termination will also affect my studies. Last year, she counselled a final-year student at UP who she says dropped out in her last semester because of the guilt and regret she experienced after her abortion. “You can go into denial and say it’s not worrying you, but then subconsciously you start to do things that you didn’t do before, like drinking excessively, taking sleeping tablets and using drugs,” she says.

Counsellors at pregnancy crisis centres, like Verster, believe that abortion is “damaging” to women, a 2014 study published in the Social Science & Medicine journal states. These organisations use terms such as “post-abortion syndrome” to persuade women who’ve had abortions that they suffer from a psychological condition. Many studies have proven that this syndrome doesn’t exist. It’s not recognised by psychiatrists.

(Mis)information: One of the Amato Centre booklets alleges that women who have had abortions could suffer from mental health conditions. (Oupa Nkosi)

Half an hour has passed since my counselling session has begun. Verster and I have hit an impasse — I’m still considering getting an abortion, but she says she can’t tell me where to go.

Verster knows where such facilities are — she mentioned at least one during my session. But she doesn’t want to be an accomplice to a murder. “We know that it’s a life that you’re carrying — it’s a baby that’s inside of you. Its heart has been beating since you were three weeks pregnant, it’s sucking and moving inside of you,” she says.

Amato volunteers aren’t allowed to refer women to abortion services. “We cannot take the responsibility to say you can go and take the life of that baby. This is what God has put inside in our hearts.”

I’m dumbfounded.

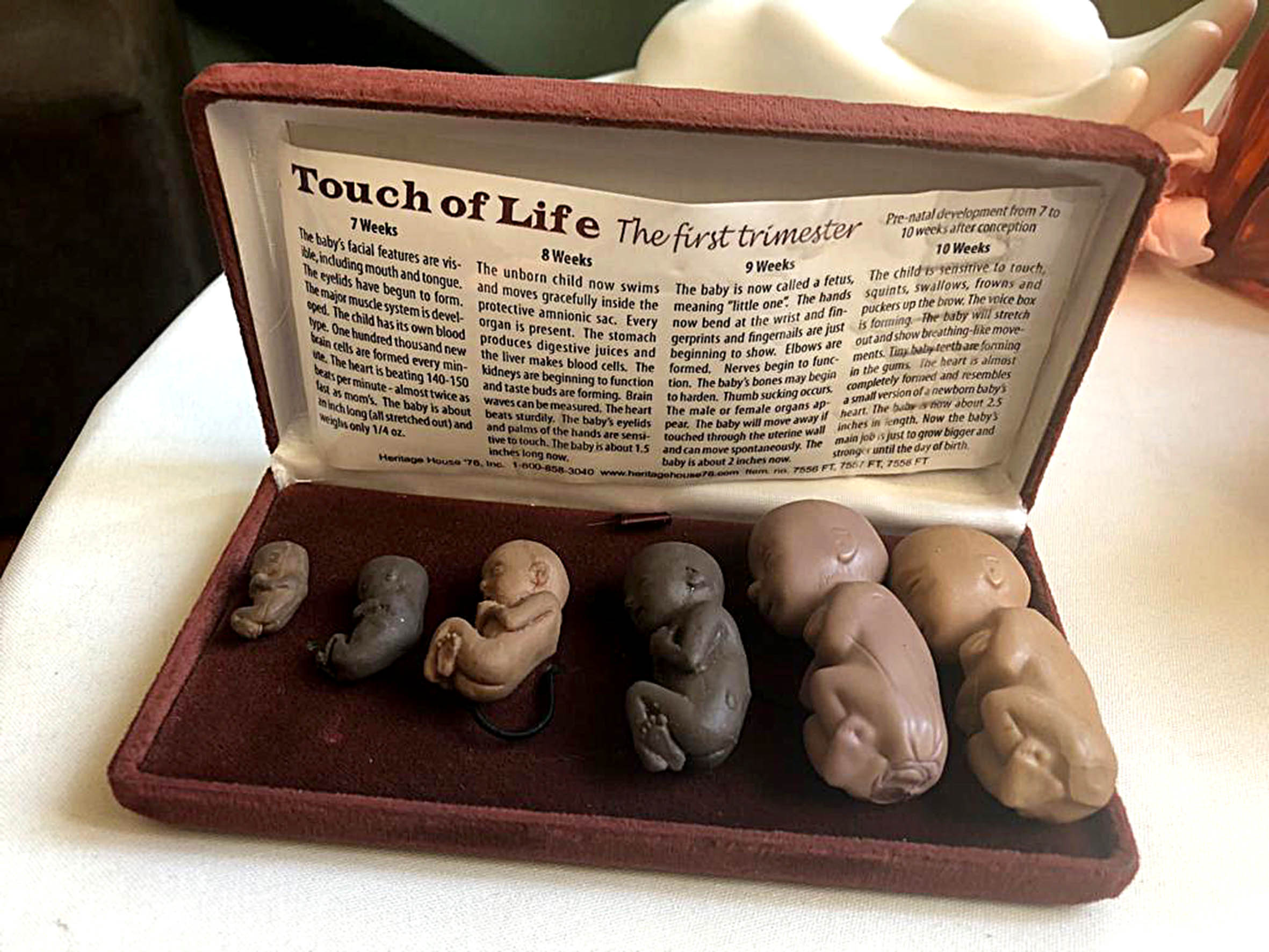

I sit across from Verster with nothing to offer but my silence. She asks: “Can I show you how big this baby is?” Reluctantly, I agree. She opens a small box almost the same size as a sunglasses holder. Six fetus models of different sizes and shades of brown are inside. She shows and hands me one. “This is how big your baby is right now at nine weeks.”

It’s quite common for anti-abortion counsellors to use fetal models during pre-abortion counselling, Jabulile Mavuso explains. Mavuso obtained her doctorate and is a researcher at the Critical Studies in Sexualities and Reproduction (CSSR) unit at Rhodes University. Her research analyses the experiences of 30 women and four health workers at three Eastern Cape public health facilities.

One of the surveyed hospitals had a relationship with a local pregnancy crisis NGO, where nurses would take the patient history and the NGO’s volunteers would then conduct the “options counselling”, she says. Some of the women interviewed in her research described the counselling as directive. Abortion was framed as dangerous, immoral and irresponsible, and women were directed towards adoption and parenting instead.

She explains: “Volunteers would, for instance, tell women the NGO could look after the baby for a period of six weeks or until the woman was financially ready to take care of the child. Parts of the services that these kinds of organisations offer are vital, but the problem lies in their approach which involves providing information that is both biased against abortion and inaccurate.”

WATCH: Here are three ways to tell whether or not you might be going for an abortion at an illegitimate practitioner

Abortion under certain circumstances has been legal in South Africa for more than 40 years. But until 1996, women needed to get approval from two independent and largely private physicians — and, in some cases, a magistrate — to get a termination, says a 1998 Guttmacher Institute report. The law made it especially difficult for black women to access abortion services.

The Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act — which came into law after apartheid ended — significantly expanded the circumstances under which abortion is legally permitted. It allows anyone the right to an abortion during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. The procedure can be performed by a midwife, a trained registered nurse, a general practitioner or a gynaecologist. Doctors can also surgically terminate pregnancies between 13 and 20 weeks if, for instance, the pregnancy poses a danger to the woman’s health or socioeconomic status, or is a result of rape or incest.

The law specifies that counselling before and after a termination is not compulsory and should happen only at the woman’s request. But the law is explicit: this counselling should be non-directive. Mavuso explains: “Counselling [before an abortion] should be done in a way that doesn’t persuade a woman into a particular course of action. It must provide information on the options available for the woman depending on their circumstances.”

In August last year, the African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP) proposed amendments to the Act. The changes included mandatory counselling before and after termination, the showing of ultrasound images and outlawing abortions after 13 weeks in the country. ACDP MP Cheryllyn Dudley told Bhekisisa this would promote informed consent.

But the health portfolio committee in Parliament rejected the proposed amendments in September.

These changes were an attempt to decrease South African women’s access to abortion services, says the chairperson of the Sexual and Reproductive Justice Coalition (SRJC) Marion Stevens. “Anti-abortion Christian organisations have been trying to change the abortion laws in South Africa for many years,” she says. “They use pregnancy crisis centres as a way to keep women out of abortion clinics. Our government hasn’t paid enough attention to providing safe abortions, and these organisations are using this to their advantage.”

The provision of safe abortions to young women and sex workers is one of the goals under the country’s latest national HIV plan. But there are no guidelines for who should counsel or how counselling should happen, says the national department of health’s spokesperson Popo Maja.

The health department teaches health workers abortion counselling during its 10-day termination of pregnancy training package. “The department is in the final review stage and the guidelines [on abortion including counselling] will most probably be available by the end of September,” he says.

Meanwhile CSSR and SRJC have devloped their own guidelines which state that counselling should happen without judgement, and counsellors must respond to the concerns raised by patients, instead of introducing their own views while giving unconditional support to patients.

Public interest law organisation Section27 says it’s difficult to say whether what organisations such as Amato are doing is illegal.

“If there is evidence that the counselling is directive, in theory, one could argue that this has the effect of preventing a lawful termination. If this is the case, the person responsible could be charged,” Section 27 lawyer Ektaa Deochand explains.

“However, proving that the directive counselling led to the prevention of an abortion would be extremely difficult in the absence of extenuating circumstances.”

Deochand says patients may have more luck reporting healthcare workers involved to their managers or the Health Professions Council of South Africa.

Touch of Life: The fetal models Amato uses during counselling sessions with women with unplanned pregnancies. (Pontsho Pilane)

I stare at the dark brown fetus model Verster placed in the palm of my hand. It looks like a small, black baby. It’s about two centimetres long, has a face and visible limbs. It even has 10 toes.

“That’s your baby,” she says.

Fetuses are about one-and-a-half centimetres long at nine weeks of pregnancy, says US-based medical research organisation Mayo Clinic.

Using models and images of fetuses is a tactic that’s widely used by the anti-abortion movement, a 2015 study published in the Culture, Health & Sexuality journal states. This constructs the fetus as “independent from the pregnant woman”, explains Mavuso. It also positions pregnant women as mothers who need to nurture and protect the fetus.

One counsellor interviewed in Mavuso’s study did not see presenting fetal models to women as manipulation. The counsellor felt it was necessary because the models are accurate and “life size”, and the graphic and concrete illustration of the fetus as a person will help dissuade women from terminating their pregnancy.

Mavuso explains: “Counsellors felt that sharing images and information about fetal development was necessary to ‘save’ the fetus and ‘save’ the woman from aborting by positioning them as a mother and therefore a protecter and nurturer of the fetus.

“You don’t know who this child is going to be when they grow up,” Verster says. “How is it [that it is] in your hands to make a choice to cut off that child’s potential in life?”

I don’t respond, but Verster looks me straight in the eye.

“Think about Madiba … His mother could have said ‘no more children’ and we would have never had a Madiba,” she says.

Again, I’m speechless.

Eventually, I tell Verster what I think she wants to hear. “I think I will keep the baby.”

She smiles and asks to pray for me.

We join hands and bow our heads. “Lord, you have brought Lerato here today. May she sit with you and talk to you about her future and may you guide her in all her choices … In Jesus’s name, I pray. Amen.”

Right of Reply: Our counselling is not ‘directive’, says Amato

The Amato Centre denies that its counselling is “directive”. “We explore the four options a woman has when facing an unplanned pregnancy: abortion, parenting, adoption and foster care. We discuss the pros and the cons of each option and empower our client to make an informed choice,” Mariska Verster* said in a written reply to Bhekisisa’s questions about its services. Verster also denied that she tells clients abortions regularly lead to negative emotions, as Bhekisisa’s reporter was told when she went undercover. “We believe that if an abortion is done in a professional and safe environment, there is very little risk of damage. That is why we work … with the UP Health Services Campus clinic where they make referrals to safe and credible abortion clinics,” she said. She said Amato doesn’t receive funding from right wing Christian organisations in the US, rather from “private individuals”, whom she cannot name without their consent. Verster denied that Amato operates at Boston College and Tshwane University of Technology. The Arcadia office has closed down since our reporter’s visit and is only based at the University of Pretoria.

* This is a pseudonym