A refugee camp on the border with Nigeria. (Shola Lawal)

Tens of thousands of English-speaking Cameroonians have fled the country ahead of the presidential vote

Ogoja — On October 7, Cameroonians will vote for their president after a long and draining campaign. Paul Biya, the 85-year-old president who has been in power for 35 years, remains the favourite, but his likely re-election takes place against the backdrop of war.

In the north, the army is fighting Boko Haram militants, which is characterised by human rights violations on both sides.

And in the southwest, a civil war against English-speaking secessionists who are demanding independence for Anglophone Cameroon — a region that has long been marginalised by the predominantly Francophone government.

The secessionists view the election as illegitimate. They have told their supporters not to vote and have pledged to attack polling stations.

Matthew (19) will not be voting. He asked that his full name and location not be disclosed. He’s speaking from somewhere on the Nigerian side of the Nigeria-Cameroon border, in a camp with thousands of other refugees, none of whom will be able to cast their ballot.

He says he is a rebel fighter. He came here several days ago, risking arrest by Nigerian immigration authorities, to visit his mother, who was forced from her home as a result of the unrest. Like many others, she fled into Nigerian villages with nothing but the clothes on her back, her survival at the mercy of local residents and aid organisations.

Matthew speaks in a voice that sounds far older than he is. His face has grown lines from the corners of his mouth, spreading outward, and his arms are thin. “I’m fighting because I can’t sit and fold my hands and watch innocent ones being killed, mothers being maltreated,” he said. “If I don’t fight for myself I don’t think I am safe, so it is better for me to rise up.”

He intends to go back across the border, to rejoin his fellow freedom fighters. This could be the last time he sees his mother.

Republic of Ambazonia

Matthew is one of hundreds of armed militants who have fought the Cameroonian army in waves of violence that have left at least 400 dead, according to Amnesty International. The Cameroonian government calls them terrorists.

Although the armed groups are fractured, and don’t share identical aims, most are fighting for independence for southwest Cameroon — for a new republic to be called Ambazonia, after Ambas Bay, a missionary settlement for freed slaves established in 1858.

The militants’ grievances are rooted in bitter colonial history, in which parts of this region were carved up by different foreign powers. They are also rooted in decades of misrule by Biya’s administration, which has long discriminated against the English-speaking minority that makes up 20% of Cameroon’s 24-million population.

Previously administered by the British and French colonial governments, Southern Cameroons and Western Cameroons were merged as a single independent state after a referendum in 1961. Prior to that, Southern Cameroons enjoyed brief autonomy as a United Nations trust territory. Secessionist agitations stretch as far back as the 1980s, when Fon Gorji Dinka, an Anglophone lawyer, was arrested for distributing pamphlets declaring a “Republic of Ambazonia”.

In late 2016, Matthew joined the Anaconda Squad, a rebel group, after watching his friends being shot dead by the army.

Anglophones demonstrating against the creeping imposition of French language in schools and administrative positions had been shot at, arbitrarily detained and forced to go without internet or mobile connectivity for months.

On October 1 last year, local leaders declared “independence”.

Thousands of innocents have been caught in the intense fighting that followed: Amnesty International has documented incidents of torture, arbitrary arrest and destruction of property by the military. Entire villages have been razed and people were burnt alive.

The rebels have also been implicated in human rights violations. They’ve attacked teachers refusing to participate in civil disobedience tactics such as strikes and “ghost town” protests, and have burned down close to 40 schools. Amnesty says rebel groups have killed 44 members of Cameroon’s security forces.

There is a mismatch in capacity between the opposing armies: the rebels use hunting rifles and charms to fight the government’s United States- and French-trained forces.

‘Elections will not hold’

On a recent Thursday afternoon, Prisca Otim arrived at a refugee settlement, funded by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), in Ogoja in Cross River state after hiding in thick forest for months. Children in the camp kicked a ball in the sand, sending red dust into the air. Dragging a sack and two clinging children, she queued to register for a temporary tent.

Otim’s husband had been killed by soldiers who invaded Mbakem village in southwest Cameroon. She still wears all black clothing, her head shorn in mourning. She had brought her children and a few belongings hastily gathered together across land and water. With no money, Otim had to beg for transport to the UNHCR facility.

Now there is hope for the young mother. She will be provided with a brick house — 500 permanent shelters are already being constructed for the refugees here. Otim’s children will be sent to schools in Ogoja to facilitate integration. The land that houses the settlement was provided by the Cross River government and is about 50 hectares, according to officials.

Almost 50 groups are being resettled here. UNHCR officials say about 200 refugees have been lodged, but that is nowhere near the numbers that need to be catered for.

Although 21 000 refugees have been registered in Nigeria’s south, emergency officials say the real numbers could be up to 70 000.

At least 160 000 are displaced in Cameroon, according to Amnesty International, some hiding out in hard-to-reach places. Many more are in unregistered camps in Akwa Ibom and Taraba states.

Yet the numbers are expected to rise further. The fear of violence associated with the upcoming election is sending hundreds more across the borders.

Valerie Agbor (26) trekked into the country in September. A communique stating that movements in the region would be restricted during the elections forced him and many others to leave. Villages in the region have emptied out and offices are deserted.

Valerie Agbor. (Shola Lawal)

“Southern Cameroon is one big ghost town,” Agbor said.

But Matthew and his Anaconda Squad insist they are not going anywhere.

“I can tell you that elections will not hold in Ambazonia,” he vowed, his small frame swaying on the mat he sat on.

Many refugees here sympathise with the fighters and agree that elections should be put off in the south. Although Biya formed a language committee to address the crisis last year, most claim the effort was too late.

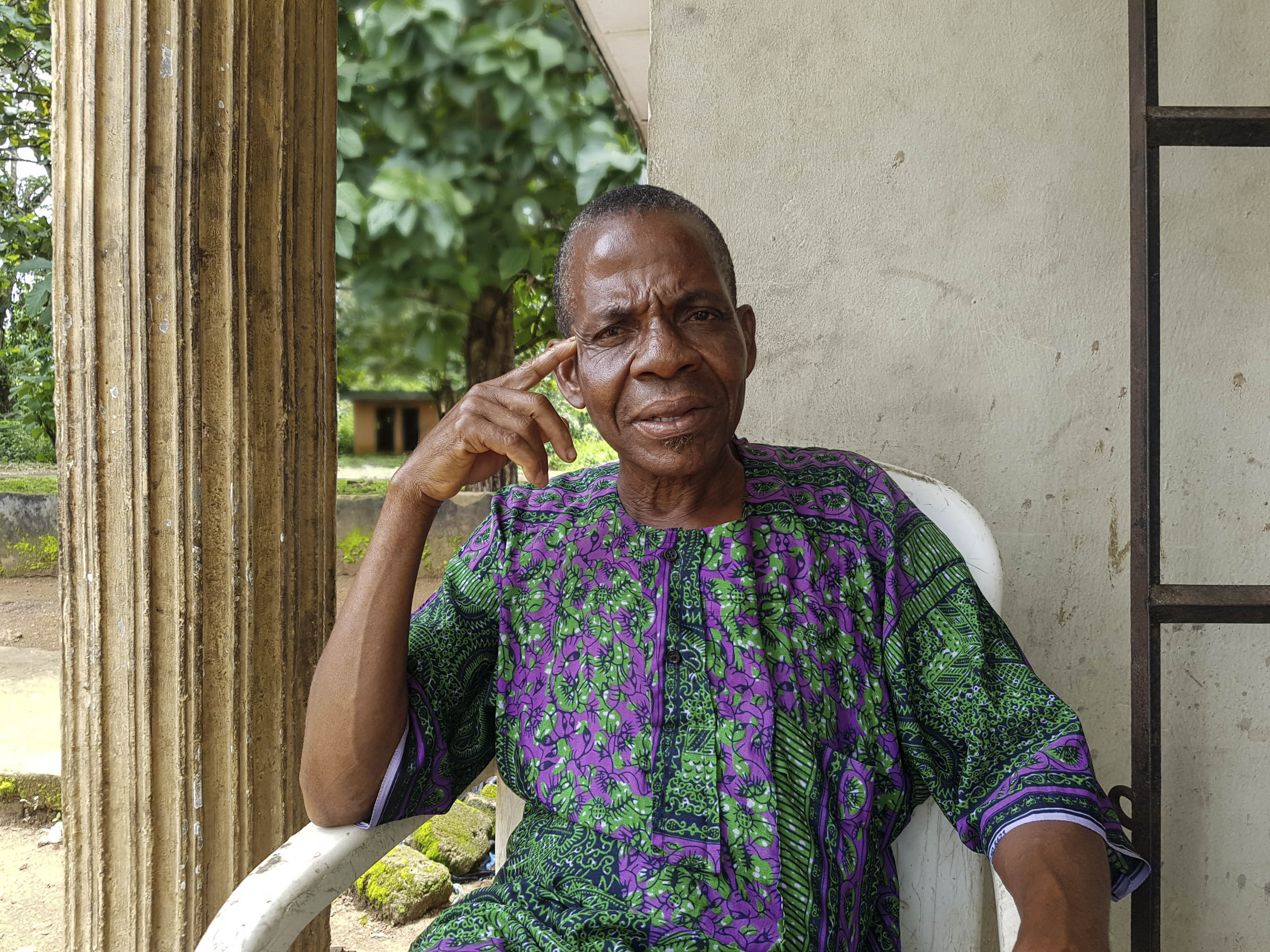

“We don’t want to vote,” says Patrick Assam, a 71-year-old who fled to Agbokim village months before. “We want the restoration of Ambazonia.”

Patrick Assam. (Shola Lawal)

Matthew says: “I have started something which I can never stop.”

He, like most secessionists and refugees, is not willing to enter into a dialogue with the government or go back to the status quo.

“I am ready to fight till the death,” he said, “ because a dead man is not scared of a coffin.”