There are some features of administered prices that the state cannot control, such as the basic fuel price, which is influenced by international crude oil prices and the exchange rate. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Administered prices have been increasing well above inflation recently, hurting consumers and businesses alike, eliciting promises from President Cyril Ramaphosa to address some of them in his recently announced stimulus package.

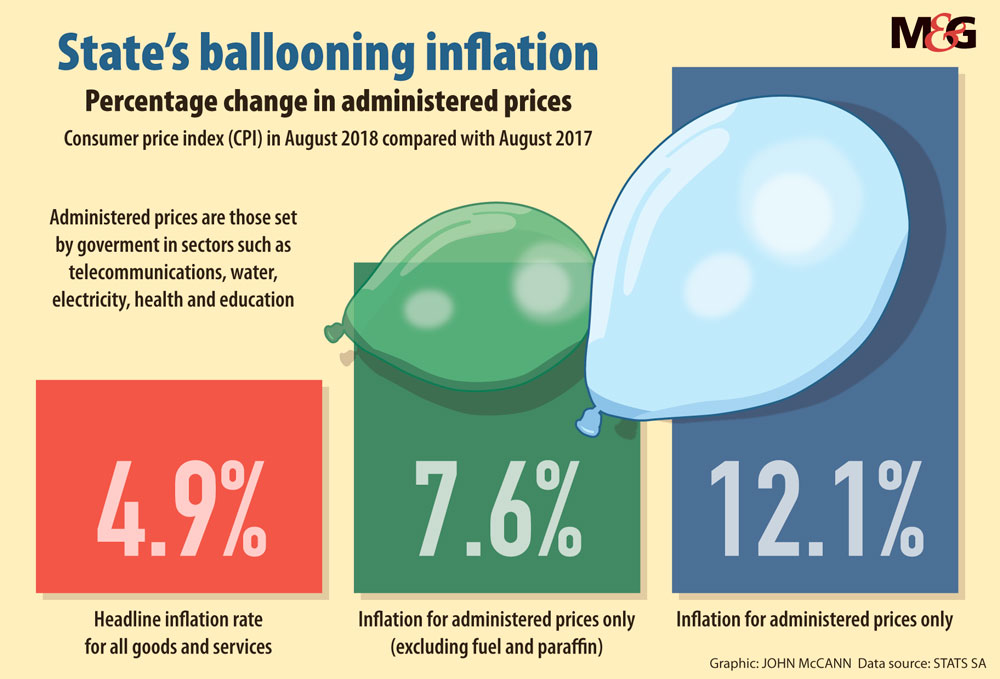

The latest consumer price index (CPI) released by Statistics South Africa showed that inflation for all goods had increased by 4.9% year on year, but administered prices had increased by 12.1% during the same period. Excluding fuel and paraffin prices, currently major drivers of administered price inflation, these prices still rose by 7.6%.

Administered prices are those determined or influenced by the government or a government agency, without any reference to market forces, according to Stats SA.

Products and services that are subject to administered prices include municipal rates, water, electricity, public transport costs — including train, motor licences and motor registration costs — and school and tertiary education fees.

An examination of administered prices using Stats SA data shows that, in the past two years, increases in administered prices have risen sharply above overall inflation rates.

Top of mind for many South Africans has been the fuel price, which reached record levels of more than R17 a litre this week.

Since September 2016, fuel prices have risen 33%, and the cost of items such as water and education have risen by 19% and 14.2% respectively. There are a range of factors contributing to these increases, says Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings, some of which the government cannot control. For instance, the largest part of the petrol price is the basic fuel price, which is determined by international crude oil prices and the rand-dollar exchange rate.

A large portion of the fuel price also consists of taxes such as the fuel levy. This tax has risen an average of 11.4% between 2009 and February this year, Lings says.

The state could reduce this tax, which would provide short-term relief. But it would have to make up the lost revenues, either by borrowing or increases in direct taxes such as personal income tax. “Either way … we are going to be paying for this,” he says.

But there are factors the government can address, not least of which is the effective operation of state agencies, including the major state-owned enterprises (SOEs), such as Transnet and Eskom.

This includes managing wages in these entities, as well as in the broader public sector, in which salary increases have outpaced inflation, he says.

It also includes ensuring that the costs incurred do not amount to wasteful expenditure and that adequate levels of maintenance to avoid expensive and large equipment upgrades are sustained.

Eskom applies to the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) for electricity tariff increases, which is included in the CPI. Transnet operates the country’s freight railways, its fuel pipelines and its ports. The prices for ports and pipelines are regulated by the National Ports Regulator and Nersa respectively. But freight rail costs are not regulated.

Although items such as port charges are not included in the CPI, these charges become an indirect cost, Lings says.

Electricity price hikes have moderated somewhat in recent years, partly because of Nersa’s adjudication, including by allowing extensive public comment. But this was not before electricity prices rose rapidly after the country faced a power supply crisis in 2008.

Work done by the state think- tank, Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies (Tips), found that increasing electricity prices weighed heavily on manufacturing and heavy industry because, although Eskom drove the increased electricity costs, most businesses are also subject to municipal electricity charges. It found that Eskom’s average unit price for power more than doubled between 2008 and 2016.

Persistent concerns about the financial management of government entities, ranging from local municipalities to major SOEs, have also fuelled public discontent over administered price increases.

But Ramaphosa has promised to review port, freight and electricity tariffs in a bid to reduce the cost of doing business.

“It is not sustainable for SOEs to increase tariffs in order to strengthen their balance sheets,” Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan said in a recent response to questions.

“This is passing the burden onto the consumer and it further erodes household incomes, the growth potential and competitiveness of our economy,” he said.

The setting of tariffs and their effect on the cost of doing business was of “vital concern” to both the government and business, Gordhan said. “As we continue to stabilise and reposition the key SOEs such as Eskom and Transnet, every effort will be put into managing the levels of tariffs.”

But he drew attention to the contribution the private sector had made to some of these problems.

“The current bloated management structures, the doubling and even trebling of procurement costs through corrupt practices and malfeasance on the part of the private sector — and covered up with the help of auditors [and] consulting firms — are amongst the critical issues that the boards and the [department] are addressing,” he said.

Where is inflation being felt?

Although administered prices have risen, overall CPI levels remain relatively contained in the South African Reserve Bank’s target band of between 3% and 6%.

According to Lings, this indicates that companies are working hard to absorb some of these costs and not passing them on fully to consumers

![M&G - Administered Prices [TEST]](https://plot.ly/~Jacques_coetzee/205.png?share_key=g8eNyMh2SuSY2qKklC7PSY)

“Companies absorb some of these costs so the net effect is that the inflation rate as a whole remains mostly under control, even though administered prices can be [in] double digits,” he says.

But he warns there comes a point at which a business can no longer manage the pressure on its margins and may take dramatic measures to manage costs, such as with retrenchments.

These effects are already being felt, he says, pointing to the latest quarterly employment survey, which showed that 69 000 formal-sector jobs were shed in the second quarter of the year.

Businesses may also choose not to expand or grow their operations, Lings says. “All of this cut-back ultimately does stunt the growth of the economy.”

Another complicating feature of inflation is the difference between what Lings calls experienced inflation and the technical measurement of inflation. Costs for items in the consumer price inflation basket that are rising more modestly are not goods individuals buy regularly, he says.

For example, the prices of new vehicles have increased by 2.9% year on year. But consumers do not often buy new vehicles, although they are regularly confronted by the cost of filling fuel tanks.

Maarten Ackerman, the chief economist of the wealth management firm Citadel, says administered prices make up just over 16% of the total inflation basket and, depending on how these are managed, they can have either a negative or a positive effect on the economy.

Given that they are being set at relatively high levels, administered prices are keeping inflation levels “on the higher end overall”.

“You could also argue that as a result … the Reserve Bank is likely to keep interest rates at higher levels than what they might be,” he says.

From a business point of view, higher administered prices are creating a very tough environment, making it difficult for businesses to increase their competitiveness against other industries, he adds.

Lumkile Mondi, a senior economics lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand, describes the president’s plan to address some of these issues as “very encouraging”.

Administered prices have contributed to keeping overall inflation stubbornly high, even during times like now, when South Africa is experiencing a technical recession, he says.

Administered prices, besides increasing the input cost of products and services for many firms, also make it difficult for new, small companies to enter the market because costs are high.

Crucial to addressing some of these issues will be to introduce competition in the sectors where the SOEs enjoy a monopoly — and even to privatise some of them — he says.

The state also needs to find ways to manage its finances better so that it does not have to rely on indirect taxes such as the fuel levy for revenue.