The treatment plant is not designed to treat water from factories that discharge fats, and sewerage pipe continue to leak. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Standing on the highest hill in Delmas, you can see the modern story of Mpumalanga playing out in every direction. A mix of dust and haze fades out the horizon and washes up into the light grey sky of a spring day.

The dust comes from coal mines. Their waste dumps create oddly straight lines on the near horizon. Double-trailer trucks roar between these and Eskom’s coal-fired power stations, which are clustered in this western part of the province. The tar roads are rutted and the surfaces broken as a result of the weight of these trucks. Kilometre-long dust clouds follow the trucks that take shortcuts along gravel roads.

The landscape is still coloured in a palette of faded pastels, as the area waits for the first sustained rains of the planting season. Between the mines, grain silos and chicken farms, potato and maize fields wait for seeds to be sown. These have been ploughed — neat furrows of torn-up, blood-red earth waiting in anticipation.

With little rain, the only green is at the bottom of each valley, where invasive tree species thrive in the rivers that flow from Mpumalanga. Their water brings life to the province’s farms, residential areas and industry, and eventually spills into the Indian Ocean, 500km away.

For Delmas, the water and its proximity to Johannesburg is why it exists. Farmers can grow vegetables and raise chickens, which are then packaged and sent to the shop shelves of the metro.

The highest hill in town looms over the largest of the factories involved in this process — McCain Foods. It is surrounded by a 4m wall. A stream of trucks overloaded with potatoes feeds the factory. Black and white smoke rises from it.

McCain is one of many medium-sized factories in Delmas. These release a mixture of waste, which ranges from polluted air to bloody bags of animal waste, as well as raw sewage.

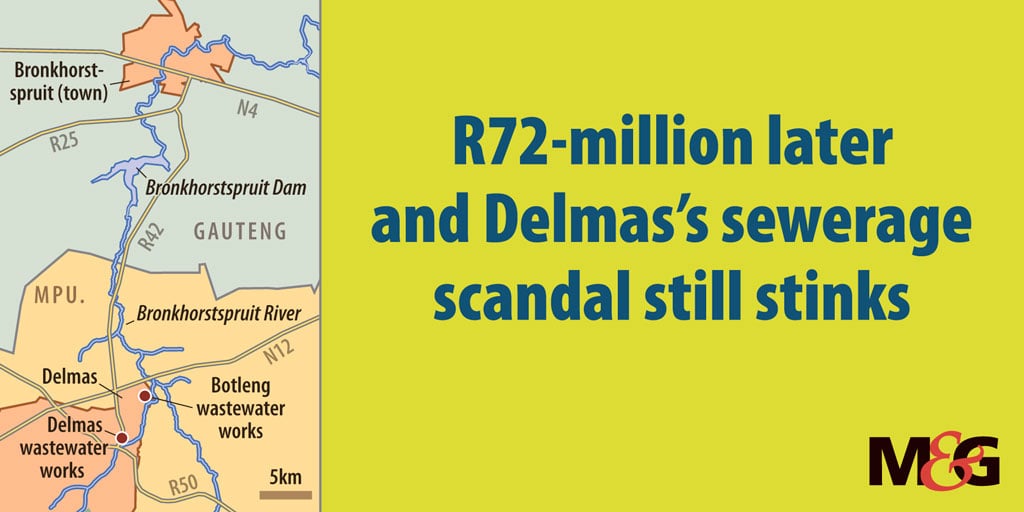

Delmas has a wastewater treatment plant, across the road and downhill from McCain. Another plant treats waste from Botleng, the apartheid-era township built 2km away.

A path across the polluted stream connects Botleng township and Delmas. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Both plants are in the middle of a R72-million upgrade. The Mail & Guardian reported last year on the effect of untreated waste from the Botleng plant, with so much flowing into the Bronkhorstspruit Dam, 20km away, that it had turned green.

In this part of the world, many dams are green, overloaded with nutrients from sewage and clogged with water hyacinth. In response to the M&G’s questions for that article, the Victor Khanye district municipality, which includes Delmas, said the town’s main treatment plant was designed in the 1970s to treat effluent from a much smaller population.

“The plant is currently overloaded as it also treats both domestic sewer and industrial effluent, and requires an upgrade,” the municipality said.

R12-million of its R72-million budget was to upgrade this plant, but there is little evidence of this money being spent.

Well-worn paths go through the broken palisade fence, which fails to enclose two sides of the plant. Goats graze on the sewage-fed grass. The mechanical paddles used to treat waste in two of the treatment pools are idle, and solid black waste clogs up the system. Breathe too deeply and the smell of sewage burns the nostrils.

From here, waste is released into two ponds and then into the stream running along one side of the plant. The nutrients from the raw sewage going into that stream are evident in the thick clusters of reeds blocking the stream.

A hundred metres downstream, a rubble path has been built across the stream to connect the two parts of Delmas. Goats, chickens and pigs — their feet black from the mud — rummage for food in the milky-white, bubbly water.

The nutrients can help plants to grow, but the sewage can also contain E coli, Salmonella and other bacteria that cause illness and death.

The failure of the Delmas plant to treat water is, in large part, because of the sewage that it receives. Sewerage plants tend to be built to treat human waste. A delicate balance of moving parts and chemicals allows this waste to be treated to the point at which clean water can be released.

That balance is undone by the fats, oils and grease that factories release into the wastewater system. The April 2015 project plan for fixing the Delmas plant says: “Industries such as McCain Foods discharge wastewater with high concentrations of fats, oils and grease, for which the treatment plant was not designed.

“The resulting effluent is being discharged into the natural stream with dire consequences for users downstream.”

(Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

The boreholes that supply Delmas with drinking water are downstream. In the plan, the municipality says the pH of water in these boreholes is acidic, with a pH of 4 (neutral is 7). This is a result of sewage seeping into groundwater.

Acidic water from raw sewage is not unique. Some 80% of the country’s 600-plus wastewater treatment plants release untreated sewage. The M&G has reported on the problem in each of the nine provinces.

This is usually the result of municipal officials stealing money that would otherwise be used to maintain and upgrade the plants. National government then has to respond to a crisis and spend tens of millions of rands to build a new plant.

The effect of untreated industrial sewage is a hidden part of this problem. In the best-case scenario, factories treat their own waste and release it to wastewater plants. Municipal plants can then handle the waste. The 2015 Delmas plan says smaller treatment plants need to be built at factories to do this. A plant has subsequently been built at the McCain factory.

The plan goes on to say that the municipality needs to “agree in principle with each of the industries what their allowable oil and fat production in the effluent [sewage] should be”. The municipality can then build treatment plants at each factory, with the factory paying for construction and operations.

With this in place, the municipality can then penalise factories that release too much waste. In cities, with inspectors and capacity, this is common practice. Smaller towns are not that organised, especially ones where there are many different industries releasing their own type of waste.

The water and sanitation department did not respond to questions about treatment plants at factories, but officials in the department have previously told the M&G that this is a particularly bad headache for ensuring clean water in the country.

In Delmas, that headache takes the form of diarrhoea, chest problems and headaches from contamination and the constant smell of sewage.