Priceless: A quarter of a million rand. Thats how much Cammi Morris faced paying for her lifelong hormone replacement therapy before she fought back (Oupa Nkosi)

It’s 4am and Cammi Morris, 47, is stretched out on a floral Chinese rug. She prefers this to a yoga mat when she does yoga or Pilates because it gives her a better grip. But this morning she’s not practising yoga poses and she’s not folding her legs into the lotus position.

She’s stretching her vagina.

Morris, who asked for her real surname not to be used, is a trans-woman and one of many who has had gender-affirming surgery to align the way she looks with who she really is.

These kinds of surgeries can include removing breasts, testicles or penises. Some people also have follow-up reconstructive plastic surgery procedures such as breast implants or creating a vagina from a patient’s penis.

Morris had her vagina constructed in August 2017. To maintain her vagina’s elasticity, she must use a penis-shaped stent to stretch it periodically.

But Morris’ journey doesn’t end here.

For some transgender people, including Morris, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is a crucial part of finally feeling like themselves. As part of this, people take either the hormone oestrogen or testosterone along with other drugs to help them attain the physical characteristics that society normally ascribes to the gender they identify with.

Oestrogen, for example, helps transgender women to develop breasts, Maddie Deutsch explains on the University of California at San Francisco’s website. Deutsch is the director of clinical services at the university’s Centre of Excellence for Transgender Health.

People on the hormone will also notice fat redistributing around their hips and thighs and their faces take on “a more female appearance” as fatty tissue changes there too, she says.

Transgender men, on the other hand, can take testosterone to achieve the opposite effect: fat begins to move towards the gut, the arms become more muscular and the face becomes more angular.

Because transgender men’s bodies won’t ever produce testosterone naturally — and vice versa for transgender women — HRT is a lifelong treatment.

After her morning exercise session, Morris usually takes out her favourite mug and makes herself black coffee with a sweetener. She says she’s trying to cut down her sugar intake. After coffee follows breakfast — almost always a Granny Smith apple. But before she takes a bite, she pops two tablets into her mouth — one blue, one white.

It’s her oestrogen. And, because she’s transgender, she needs to pay for it herself.

Morris has medical aid but most schemes don’t cover gender-affirming treatments such as HRT.

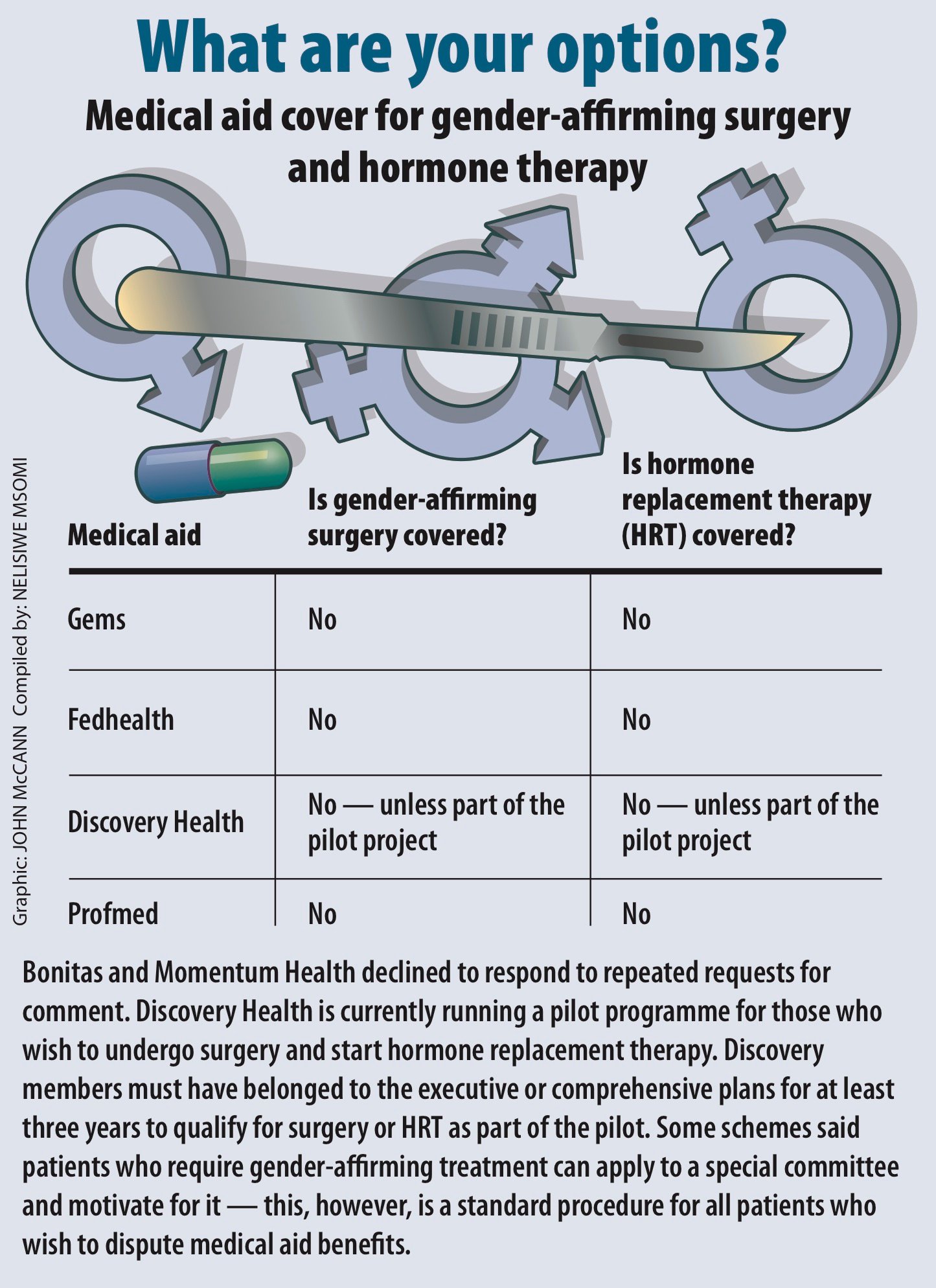

Bhekisisa surveyed six of the country’s largest medical schemes: the Government Employees Medical Scheme (Gems), Fedhealth, Discovery Health, Momentum Health, Bonitas and Profmed. Together, these schemes are responsible for more than three-million people — or almost a third of all privately insured South Africans, according to the Council for Medical Schemes’ latest annual report.

Momentum Health and Bonitas declined to comment. But the survey found that Gems, Fedhealth and Profmed require members on HRT to pay for the chronic medication out of their medical savings and when that is exhausted, eventually, their pockets.

Discovery Health is running a pilot programme that pays for surgery as well as hormonal treatment. So far it has approved care for two out of the five patients who applied to be part of the programme.

In the past, Morris tried to use her medical aid savings to pay for her HRT — but her scheme wouldn’t always pay up. Today, she spends about R800 a month from her own pocket for the daily tablets. If she lives as long as the average South African, she will have spent almost a quarter of a million rand on the medication.

She explains: “Not everybody can afford R800 a month. I find it very difficult and that’s just to maintain [my health] — it’s a basis for living.”

For decades, studies have suggested that members of the LGBTI community face an increased risk of suicide, in part because of the stigma they face.

Research published in 2008 in the journal BMC Psychiatry reviewed 25 different studies focusing on suicide and self-harm among LGBTI people and found that, overall, adolescents and adults were almost twice as likely as heterosexual people to report having attempted suicide in the past 12 months.

A 2014 study conducted among 900 transgender people in the United Kingdom found that eight out of 10 of those surveyed had thought about ending their lives. Some reported that delays in getting gender-affirming surgery or HRT contributed to thoughts of self harm.

The research, published in the Mental Health Review Journal, found that almost seven out of 10 people surveyed said they thought about ending their lives before surgery, but just 3% said the same after receiving this type of care.

To try to ensure that people in need of chronic medication don’t go without, the law prescribes that 25 lifelong conditions such as asthma, diabetes and hypertension must be covered in full by medical aids. Illnesses such as these form part of what is known as prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs), which also include emergency care, mental illnesses and heart disease.

On the road to a National Health Insurance, the recently released Medical Schemes Amendment Bill proposes scrapping PMBs in favour of a more comprehensive package of conditions and services. But it’s unclear what conditions would be included.

Right now, however, gender-affirming treatment — vital and sometimes lifelong as it is — isn’t a PMB.

Access to gender-affirming surgery and treatment has been shown to help reduce thoughts of self harm and suicide among transgender people in some studies. (Oupa Nkosi)

Why not? The answer may say more about society than it does about medicine, University of Cape Town clinical social work lecturer, Ronald Addinall, says.

“Historically, private medical aids classified gender-affirming interventions such as hormone-affirming treatment and gender-affirming surgeries as ‘lifestyle choices’ and not as quality of life priorities,” he explains.

But surgeon Kevin Adams argues that medical aids should be covering this type of care. Based in Cape Town, Adams specialises in gender-affirming surgery and says he advises patients to check whether procedures are covered by their medical aid before going ahead.

If doctors have cleared a patient for surgery and a medical aid refuses to pay, then patients should seek legal advice, he says.

Legally, medical aids that don’t cover such treatment may be violating trans people’s constitutional rights, Legal Resource Centre attorney Mandy Mudarikwa argues.

“Section 9 of the Constitution prohibits discrimination, among others, on the grounds of gender. The blanket exclusion of all gender-affirming care in the PMBs is contrary to the Constitution, specifically the rights to equality, dignity and access to healthcare among others,” she explains.

But, she says, the crux is that many medical aids continue to believe that gender-affirming treatment is a choice, rather than a health need.

“Schemes often categorise surgeries as cosmetic. Yet equality is both a value and a right in South Africa.”

But the fate of trans people could change.

The head of healthcare and life sciences at Werkmans Attorneys, Neil Kirby, says patient groups can lobby the Council for Medical Schemes to amend the Medical Aids Act on socioeconomic grounds, arguing that the cost of gender-affirming treatment is too high and compromises the right to health enshrined in Section 27 of the Constitution.

Morris is hoping to collect the evidence needed to make such a demand.

For the past 16 months, she has been gathering information on what kind of transgender care medical aids cover and under what plans. She wants to use the data to show the Council for Medical Schemes just how far away South Africa is from upholding international guidelines — and hopefully change legislation to fix this.

Discovery Health is already rethinking its benefits. For more than a year the scheme has been piloting changes to the way it funds transgender care, providing both surgery and HRT to some members. But there’s a catch.

To qualify for the pilot, people must have been a member of the scheme’s executive or comprehensive plans — among Discovery’s most expensive options — for at least three years, Noluthando Nematswerani, Discovery Health’s head of clinical policy says.

But a member of the executive plan pays almost R6000 a month in premiums.

Morris argues that this is unaffordable for most people and that members of those schemes are already likely to be able to pay for treatment out of their own pockets.

Meanwhile, Morris is a step closer to reaching her goal. After negotiations with Discovery Health and threats to take them to the Council for Medical Schemes, they’ve agreed to pay for her HRT.

“But they are going to have to process the claims manually because their system will reject it,” she explains.

“I want medical aids to play fair according to the Constitution, and implement fair support for trans surgery, which is life-affirming and often life-saving.”

This article contains a reference to death from suicide. Those in need of support to cope with issues such as depression can call the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (Sadag) on 011 234 4837 8am-8pm Monday to Sunday. If you or someone you know may be suicidal, please contact Sadag’s emergency number 0800 567 567. A 24-hour helpline is also available on 0800 12 13 14.