Frida Kahlos dedication to the communist party is obvious in paintings such as Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick

Since July, people have flocked to the first-ever exhibition of the works of Mexican Frida Kahlo in Budapest — except Hungary’s right-wing prime minister, Viktor Orbán, and his followers.

Magyar Idökhe, the pro-government newspaper, slammed the Hungarian National Museum for promoting communism. “You won’t believe it but [Leon] Trotsky has emerged in Budapest again, this time from Frida Kahlo’s bed,” it stated.

Kahlo, a leading 20th-century surrealist/magical realist artist, who widely became the face of feminism, did indeed join the communist party in Mexico, through which she met her husband Diego Rivera, famous for his frescoes that helped to establish the Mexican mural movement, but left it when he was expelled from the party. She also had a brief affair with Trotsky.

The Central European news website Kafkadesk writes that, since Orbán’s re-election in April, he has been vigorously rewriting Hungary’s cultural history.

Kahlo was just one of many who came under fire: Magyar Idökhe listed other artists, galleries and institutions that fell too far to the left.

Kahlo is best known for her vibrant dress sense, which reflected her indigenous Mexican heritage from her mother (her father was German) and her colourful, intimate self-portraits sometimes reveal her vulnerability. A tram accident caused her lifelong pain, despite the more than 30 operations, and emotional distress. My Beloved Doctor, a book published in 2007, revealed a secret kept hidden for 50 years. In her letters to her doctor, she writes of her distress over not being able to have Rivera’s children. Some of her paintings reflect her grieving. They include Henry Ford Hospital, which shows Kahlo on a hospital bed bleeding and a foetus floats from an umbilical cord above her.

Kahlo had only one major exhibition before her death in 1954 but with the wave of feminism in the 1960s her popularity rose — and continues to rise as more and more items bearing her iconic image are produced.

That Kahlo, who was born in 1907, was political should not come as a surprise. After all, the backdrop to her childhood was the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, an event that would most certainly have found a permanent place in her memory. During her time as a medical student, she found herself in social circles that were concerned with politics, art and literature and she joined the communist party in 1927.

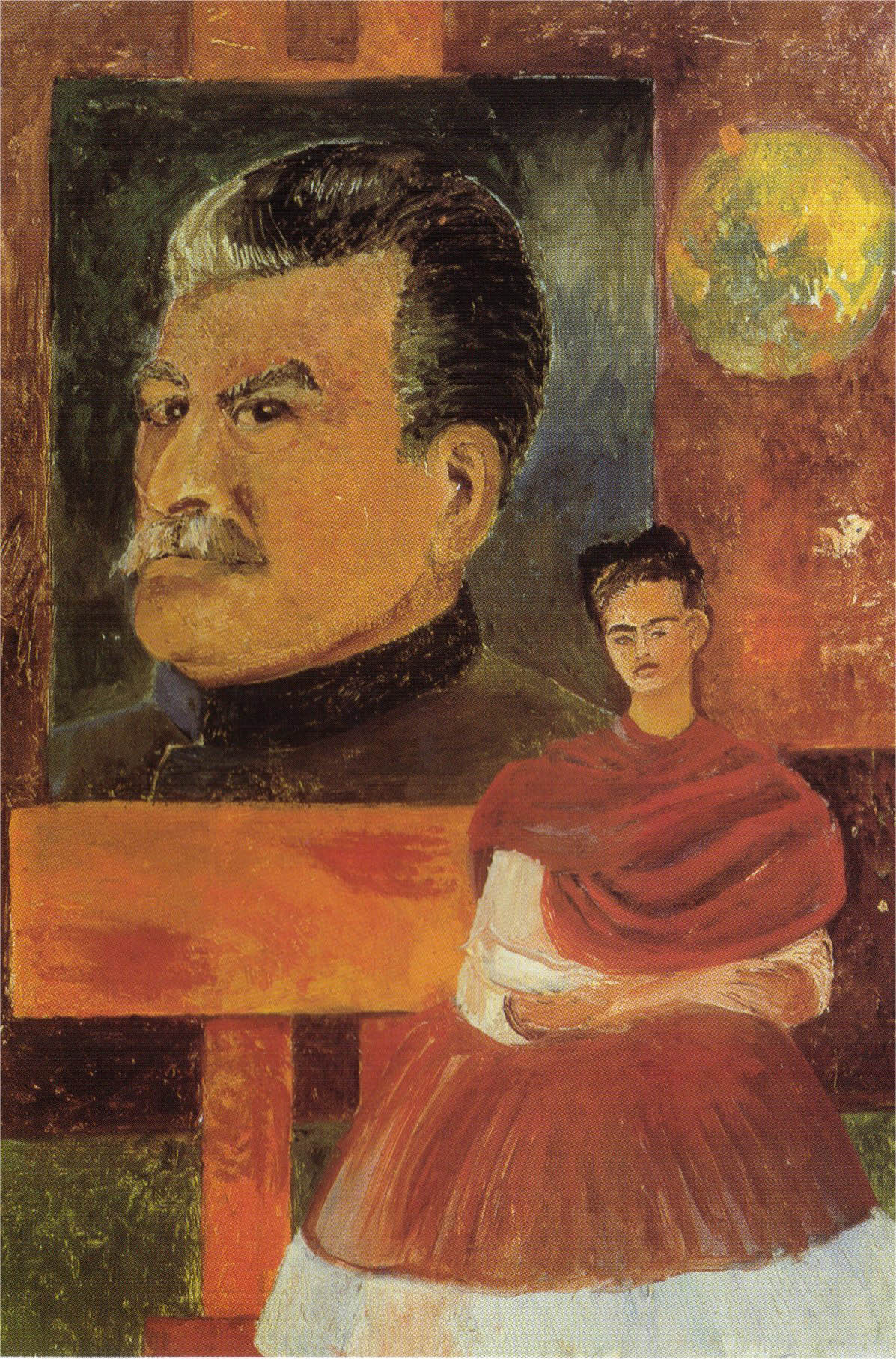

Kahlo painted these self-portraits to honour Soviet politicians Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, whom she greatly admired for being ‘pillars of the new communist world’.Her coffin was draped with a red cloth

Kahlo painted these self-portraits to honour Soviet politicians Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin, whom she greatly admired for being ‘pillars of the new communist world’.Her coffin was draped with a red cloth

Both she and Rivera could be found at workers’ protests and the meetings of socialists. Kahlo fought for the rights of refugees to seek safety in Mexico during the Spanish Civil War and, later, in World War II. She also helped them to settle in Mexico, finding them jobs and places to live.

Trotsky entered the lives of Kahlo and Rivera when they petitioned the Mexican government to grant the Soviet politician and revolutionary asylum, and gave him a place to stay in their home. He would not be the only political radical to take up residence there.

Trotsky and his wife, Natalya Sedova, lived with Kahlo and Rivera from the beginning of 1937 until April 1939. During this time,

Kahlo and Trotsky became lovers. Towards the end of their relationship, she painted a portrait of herself for Trotsky. “To Leon Trotsky, with all my love, I dedicate this painting on 7th November 1937,” she wrote.

Trotsky was not the only communist to find a place in Kahlo’s bedroom: her headboard was adorned with the portraits of prominent communist leaders: Mao, Marx and Lenin, as well as Trotsky.

Looking back from perspective the 21st century, her devotion to the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, is surprising. But it is important to remember that the regime of terror and the purges conducted under his leadership came to light only after Kahlo’s death at the age of 47 in 1954. She painted Self-Portrait with Stalin in the last days of her life, to “serve the party” and “benefit the Revolution”. To her, he was a hero, a crucial player in the creation of a utopia that saw all people as ultimately equal. (Yet Trotsky had been expelled from the communist party in the Soviet Union and had continued to oppose Stalin, writing The Revolution Betrayed, which was published in 1937.)

Towards the end of her life, Kahlo sought out the ideals of communism in a way that many of the sick and dying find religion. Despite her declining health and doctors’ advice, she found a renewed belief in the cause. You can see it in her painting, Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick, in which she stands between a pair of giant hands gently holding her body; a white dove swoops in from the left and Marx looks down from the right. It was one of her last paintings; it lay unfinished on her easel when she died.

Kahlo refused to back down on a range of issues and causes right up to the end. She can be seen in a photograph from July 1954, weakly holding her fist up in protest against the United States’ involvement in Guatemala; the Central Intelligence Agency was behind the coup in that country. She died 11 days later after a painful and protracted ordeal.

Kahlo’s funeral reflected the beliefs that she held most passionately in her life. Her coffin was draped in a red cloth bearing the symbolic hammer and sickle in homage to her communist beliefs. More than 600 people attended her funeral, throwing away their propriety in their grief.

A diary entry from November 1952 summarises Kahlo’s passion most eloquently: “I am a communist being … I have read the history of my country and of almost all nations. I know about their class struggles and their economic conflicts. I understand very clearly the material dialectics of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Mao Tse. I love them as the pillars of the new communist world.”

Many people find themselves drawn to Kahlo as a symbol of hope and defiance in the face of pain and trauma, and draw comfort and support from her image. But its overwhelming popularity has probably played a part in obscuring the radical nature of Kahlo’s politics and beliefs. After all, it is her paintings that reflect her political doctrines.

Looking at the current global situation, with the rise of right-wing politics in the United States and many countries in Europe, and the repression of so many people in many other parts of the world, perhaps it is time for people to start rediscovering Kahlo’s radical ideals: her refusal to play the part that is expected of a woman; her support of an ideology that she believed in; the dedication with which she resisted the rise of Western culture and imperialism; the opening of her house to those fleeing fascism; and making it a point to immerse herself in the history and culture of her people.