Government and the private sector are stopping the spread of invasives by about 3% each year, says the writer.

South Africa is a semi-arid country. The plants and animals that have evolved to live here grow slowly, taking just enough to get through the good times and keep stores for the inevitable droughts. This makes local ecosystems vulnerable to competition from plants and animals that take

in a lot of water and nutrients and grow quickly. The damage done by invasive plants alone is R6.5-billion every year.

The total of ecosystem services — the free benefits such as erosion prevention, pollination or pest control that a functioning system gives to the economy — is R152-billion a year.

This is according to a tome of research put together by the South African National Biodiversity Institute. Its nearly 400 pages describe alien species and what happens when they become invasive (that is when they kill indigenous species).

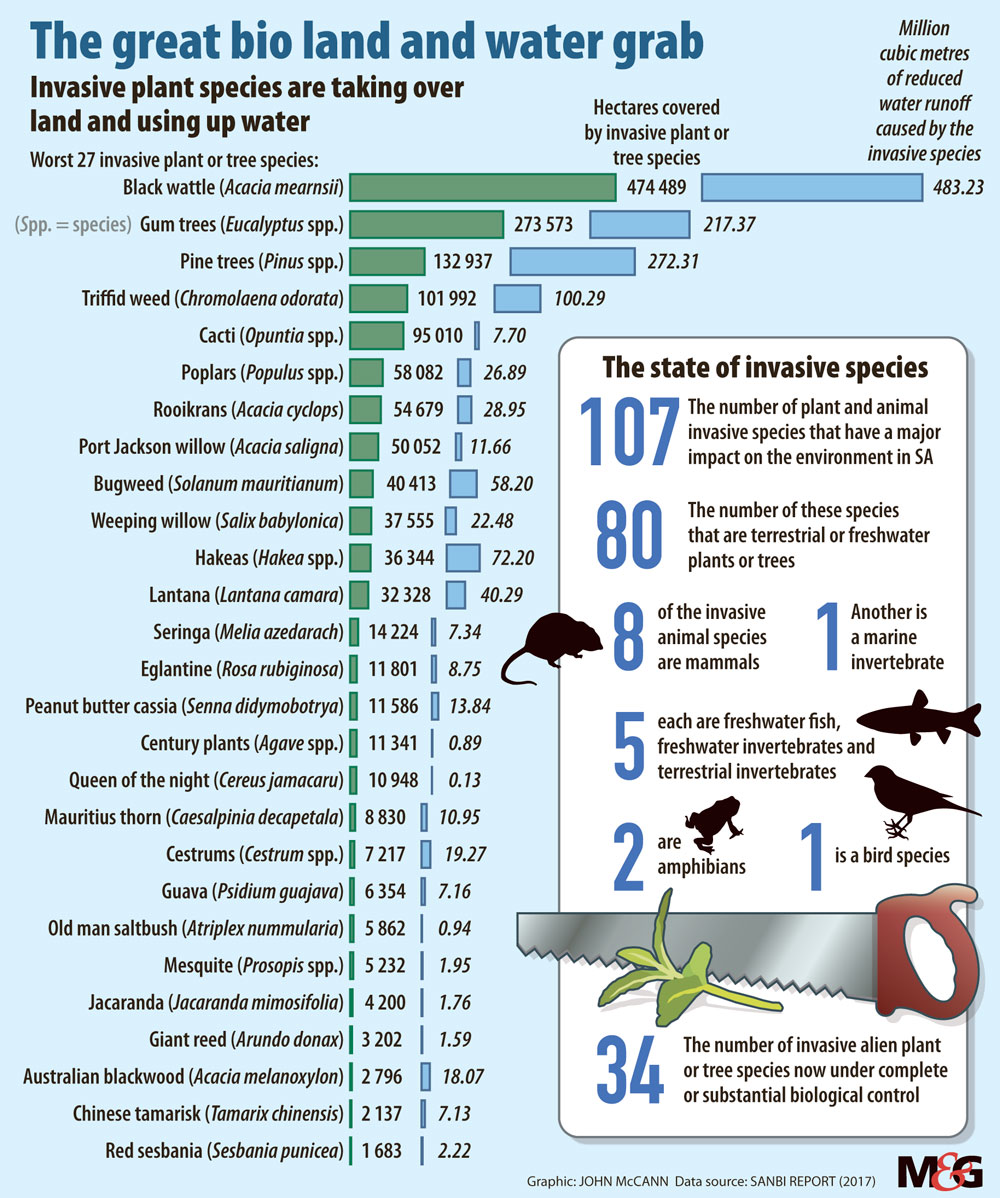

The Status of Biological Invasions and Their Management in South Africa is the first report of its kind in the world. It notes that there are 775 invasive species (mostly plants) in the country and 107 of these species have a “major or severe impact on biodiversity and/or human wellbeing”.

These plants and animals use billions of litres of water, fuel violent wildfires, kill indigenous species, make people sick and take away land from animals. The report says that 1% of the country’s terrain has been taken over by invasive species. This has denied 115 000 large animals, such as cattle, the space to graze.

Government and the private sector are stopping the spread of invasives by about 3% each year. It costs the department of environmental affairs, alone, R1.5-billion a year.

Invasives are growing by between 5% and 10%. Battles are won, but the war is being lost. Plant invasions now cover 80 000 square kilometres of the country and suck up 7% of our water.

The greatest negative effect is in the Eastern Cape and the Western Cape, where dams are losing their water to invasive trees in their catchments. The report notes that this exacerbated the water crisis in Cape Town.

And, according to the report, unless more attention is paid to fighting invasives, it will only get worse.

It gives as an example the 72 official ports of entry into the country. Only one of these — OR Tambo International Airport — has a team that looks for passengers bringing in plants or animals. With an increase in trade and travel, the report says there is little stopping aliens from entering the country.

On the upside, by identifying all the problems, the country has a starting point for dealing with them. South Africa now has an advantage over other countries, which can only respond to invasions after they wreak havoc. This tool could save the economy billions of rands.

The report found that, for every R1 spent controlling invasive species, between R8 and R3 000 is saved in damage not done to ecosystems.

A recent study in California, looking at the value of trees in that state, found that its 9.1-million trees were worth R14-billion to the economy each year. It broke this value down: R140-million for the carbon dioxide the trees store; R250-million for other air pollutants they remove; R600-million from the trees absorbing heavy rainfall to avoid floods and damage; R1.4-billion saved in energy because trees prevent heat going into buildings that then need to be cooled; and R12-billion in improved property prices. Armed with growing knowledge, the report says South Africa can perfect its fight to preserve indigenous species and their benefits.

Five of the worst

- The honey mesquite (from North and Central America) is a shrub or small tree that was introduced to feed livestock in arid areas. It has invaded large parts of the Karoo. Bids to stop it spreading have failed.

- Black wattle (from Australia) has a variety of uses and was introduced for its tannins, as firewood and for construction. The species has invaded the humid parts of the country, especially along rivers. Biological controls have managed to slow down their seed production.

- Pine trees (from Europe and North America) were introduced as a source of quick-growing timber. They have invaded large parts of the Cape fynbos kingdom.

- Smallmouth bass (from North America) were introduced for freshwater angling. They have taken over rivers in the Western and Eastern Cape. Bass can’t be eradicated as indigenous fish would be killed in the process.

- Mediterranean mussel (from Europe) was accidentally spread by ships. It has formed dense beds that monopolise space along the rocky shores of the Eastern Cape.

The grey-area species

Pine trees and rainbow trout are the epitome of invasive species that regulators want to get rid of, but they create jobs and boost the economy so this is unlikely to happen.

Plantations of pines were planted in the 1930s and, by the 1970s, government was running programmes to stop the trees choking rivers. Trout have been here for more than a century and are impossible to eradicate once they’re in a river system.

But pines suck up huge volumes of water, and trout and bass kill off indigenous fish species.

The report concludes for pine that: “Suitable compromises have not been found, nor do they seem possible.”

Trying to eradicate trout and bass would endanger indigenous fish.

How to kill an invasive species

In most cases it is impossible to wipe out a species once it has invaded. One of the real problems is that they become part of ecosystems and other organisms evolve to live with them. This means that removing them has untold knock-on effects.

Rather, officials try to contain a species by introducing its natural predator or cutting it down.

There have, however, been three successful attempts out of nine to eradicate a species: feral cats on Marion Island and two species of bug on the continent.

Two attempts, mentioned below, had too many unintended consequences for the experiment to be repeated.

- Smallmouth bass were killed in one section of the Rondegat River in the Western Cape, with a chemical introduced into the river between a waterfall and a weir.

This stopped it going downstream, but other fish died and the case proved that bass are here to stay. This eradication attempt cost R3.8-million.

- On Robben Island, more than 150 domestic cats were shot or trapped in the mid-2000s. This controlled the problem but led to an explosion in rabbit numbers, leading the authors of this report to conclude that “single-species eradication programmes could have devastating impacts on the island’s ecology”.

Failures

- Pompom weed’s range has grown by 670%.

- Famine weed’s range has grown by 493%.

- Red river gum’s range has grown by 180%.

- Eucalyptus’ range has grown by 61%.

Working for water is not an adequate focus

The Working for Water programme is the primary tool by which government tackles invasive species.

It started in 1995 with a budget of R25-million. It now gets R1.5-billion a year and employs nearly 40 000 people on 385 projects around the country. The employment number is the reason that it continues to receive political and economic support, which allows it to do its job of cutting down invasive trees and clearing out wetlands. But the report has harsh criticism for this approach: “On the one hand, it [the focus on creating jobs] is absolutely essential for the retention of the political support that ensures funding, but on the other, it restricts the ability to focus funds where they are most needed for ecosystem restoration purposes”.

Focusing on jobs means that the programme has to squeeze out the most jobs per rand spent. “This reduces the programme’s ability to adequately invest in planning and monitoring, which would be relatively expensive and would increase the overall cost per-person-per-day.”

It means projects that create the most jobs are the focus, rather than those that destroy the most invasive species. “Despite the expenditure and localised successes, plant invasions have nonetheless generally continued to grow, some substantially,” says the report.