The children stayed in a military barracks in Oudtshoorn, which also served as a school.

On November 11, the Polish diaspora in South Africa honoured the 500 children — among the 1.7-million Poles forcefully removed by the Red Army to labour camps in Siberia during World War II — who found refuge in Oudtshoorn in 1943. They are the foundation of the community of second-, third- and fourth- generation Siberian deportees, who call themselves Oudtshoorniacy in honour of their new home

As a child, Irena Schneider seldom heard her father talk about his World War II experience. But, after he died, she discovered a briefcase in his bedroom cupboard. It contained pre-World War II Polish money, school notebooks, a prayer book, photographs, his South African naturalisation card and letters from her grandmother in Poland.

It was like a personal time capsule, filled with mementos that traced his deportation from Soviet-occupied eastern Poland to a Siberian labour camp and his eventual escape through Iran to find refuge at the southern tip of Africa.

“It helped me understand his past trauma and why it was difficult for him to talk about [it],” she said.

Schneider’s father, Stanisław Korzynski, was one of 500 Polish refugee children who arrived in the Klein Karoo town of Oudtshoorn 75 years ago and never returned to his homeland. Poland had become a Soviet-controlled state after the war and many were too frightened to return.

With time a community was established, called the “Oudtshoorniacy”, which today forms part of South Africa’s 20 000-strong Polish diaspora.

Its members are now spread throughout South Africa and the world, but they hold regular cultural events and gatherings to strengthen their links with Poland.

One was held earlier this month at the Johannesburg Holocaust and Genocide Centre. Second- and third- generation Oudtshoorniacy shared personal stories honouring their forefathers.

Although each of their stories may end differently, they all begin in a similar manner. Because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was occupied by Germany in the west and Russia in the east. In the dead of the night, between February 1940 and June 1941, Red Army soldiers banged their rifle butts against doors, ordering everyone to pack warm clothes, food and a few belongings into one piece of luggage. They were given only 15 minutes. Civilian men, women and children became political prisoners overnight. Their only crime was being landowners in eastern Poland’s Kresy region, which the Soviets had annexed.

Hundreds of thousands of children were deported. They were part of the estimated 1.7-million Polish citizens of all religions and ethnicities who were forcibly removed by the Soviets to labour camps in Siberia.

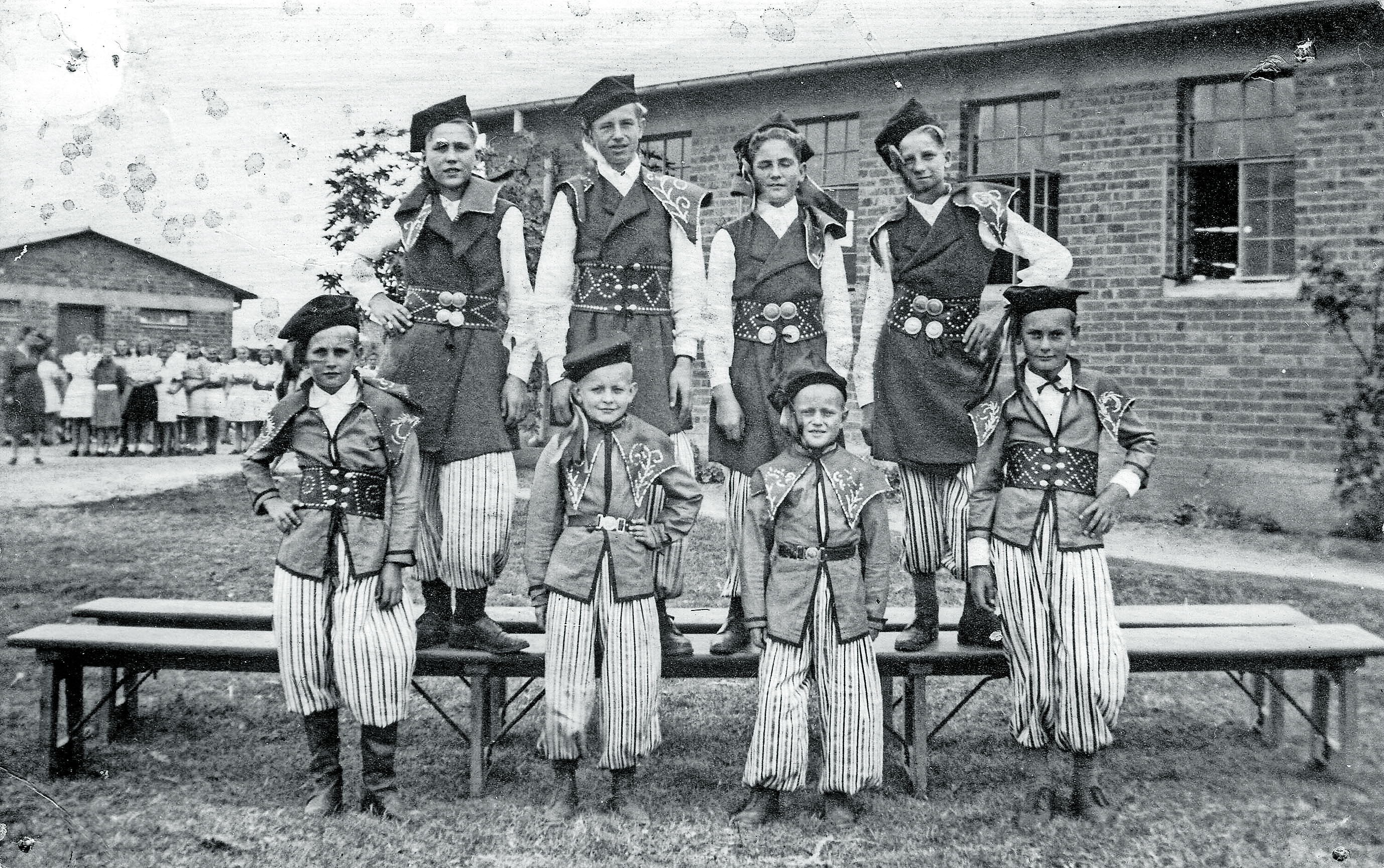

About 500 Polish refugee children arrived in Oudtshoorn in 1943 and held events celebrating their cultural heritage

They were transported in crowded cattle trucks and sealed-up train compartments to the communal barracks in the desolate gulags. After two weeks, their prayers, hymns and patriotic songs became hushed. They were to work in mines and quarries and also felled trees, even during the unforgiving winter that turned exposed skin to raw wounds.

“ ‘He who does not work does not eat’, that was the Russians’ mantra. Adults received 400g of bread, while we as children received 100g to 200g,” said Johannesburg resident Leokardia Knap, recalling her experiences.

Olenka Christie, a second-generation Oudtshoorniacy, said: “My grandmother did embroidery and crochet work, which she would trade or sell for food. That helped her feed the children and survive.”

Jan Szewczuk added: “I was given half a cup of kasza [buckwheat] for fixing shoes.”

The Sikorski–Mayski Agreement was signed between Poland and Russia after the Germans betrayed their alliance with the Soviets in June 1941. Half a million imprisoned Poles, who had survived until then, were granted so-called amnesty. They could either remain in the Soviet Union, journey to their war-ridden homeland or trek south to Uzbekistan to join the Polish Army and allied troops.

Many died on the road to freedom because of hunger, exhaustion, malaria or jaundice, leaving a trail of hundreds of thousands of unmarked graves. Those who made it back to their homeland found it unrecognisable from the birthplace they knew and loved — post-war Poland was under the rule of the Soviets.

Some families were unable to return to their hometowns, which had become part of the Soviet Union (present-day Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania).

About 115 000 Poles were evacuated from Siberia via Persia (modern-day Iran). Of those, 18 300 were children, many of them orphans or with fathers fighting with the allies. The children were sent to Commonwealth countries for safety until they could return to their motherland.

“We were malnourished and no one knew how old we were, so they guessed our ages and sent us to different countries based on that,” 88-year-old Jan Apanowicz said.

His brother and sister were sent to New Zealand and it was only in April last year that Apanowicz reconnected with his sister.

The Oudtshoorniacy children made landfall in Port Elizabeth in early 1943 abroad the SS Dunera. In Oudtshoorn, they stayed at the military barracks, parts of which were turned into a Polish school, supported by the South African government and the Polish government in exile in the United Kingdom.

The children were welcomed warmly by Oudtshoorn’s residents, who invited them to play with their children and to pick fruit in their gardens.

“But we wanted to go back to Poland once she was free,” said Janina Morawska. “That is why we had Polish teachers and studied in Polish.”

When the school closed in 1947, half the children were reunited with their families through the Red Cross, and the orphans of school-going age were sent to Catholic schools around the country and started a new life in South Africa.

General Jan Smuts and his wife Isie took an interest in the children’s lives and education

The CP Nel Museum and Saint Saviour’s Cathedral in Oudtshoorn display permanent exhibitions dedicated to the Oudtshoorniacy, who converge on the town for biennial gatherings.

Beyond Oudtshoorn and the local Polish community, few South Africans know their story.

“Once, after my mother had something to drink, she sat down with an atlas and traced their journey from Poland to Siberia and Persia. Many of these stories are lost,” said Olenka Christie.

Unless we tell them.

Iga Motylska is a Johannesburg-based freelance journalist. Her maternal grandfather, Władysław Ciaciura, was also deported to Siberia with his family but returned to Poland after the war, where she was born