Embos lament: Thandiswa Mazwais songs become tools to remember our origin stories and survive the purgatory of the present. Photo: Oupa Nkosi

The letter. The note. The dispatch. An important leitmotif of our history. Writing as an act of generosity. The song as a reminder, a quickener, an act of love.

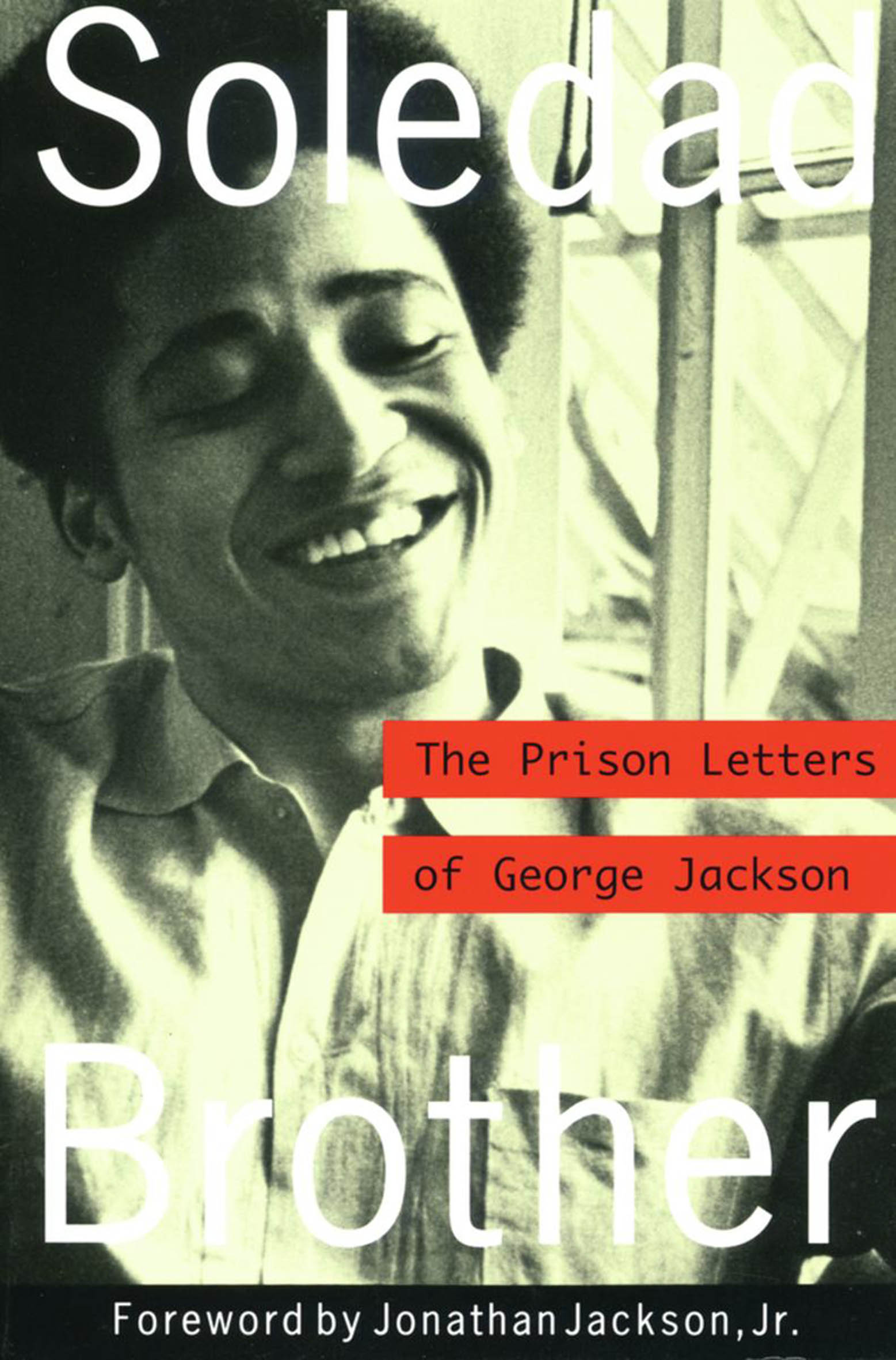

While reflecting on Thandiswa Mazwai’s performance of A Letter to Azania a few days after her show at the Lyric Theatre on Saturday, my eyes wandered to the book of letters closest to my bed. It was Soledad Brother: The Prison Letters of George Jackson. I had not read it for a while and pulled it out of the bookshelf and opened it randomly. Page 93 contains a letter written on February 23 1966, which begins simply, “Dear Mama”.

Politicised in prison after being arrested for his role in a 1960 robbery, the letter was written after Jackson has been detained for six years. Facing no prospect of release (he would eventually die in 1971 in a prison shootout during an escape attempt), the young revolutionary tells his mother that he has come to understand “never again to look for mercy, never again to hope for justice”.

A lone sentence, underlined by the book’s previous owner in pencil, reads: “Right here at this juncture of time we as a people have nothing, absolutely nothing, but each other, some fresh air, the blue and gold of day and silver at night, a clean conscience and the promise of cloudless days to come.”

In the lead-up to her show, Mazwai spoke about the idea of Azania, as a “utopia”. A promised land beyond a physical place. As a framing device, the idea of A Letter to Azania allowed us a moment to reappraise Mazwai’s work in the context of a liberation we can now consider aborted. Reduced to ashes by the humiliation of it all, the songs become necessary tools in helping us to remember our origin stories as a way of surviving the purgatory of the present.

It was important for the artist and others accompanying her to allow moments for declamation. “Your history doesn’t begin with being conquered, it begins with empire,” said Mazwai, and also that our existence precedes our definition as “black”.

The presence and not merely the poetry of Koleka Putuma contributed to what was an emotionally charged atmosphere; charged not only in the sense of the electricity of her words but also because Putuma and Mazwai’s presence in each other’s works symbolised a lengthening of “the lifeline”, as recorded in Putuma’s collection of poems, Collective Amnesia.

“The lifeline”, a roll call of sorts, could also extend to the idea of ancestry, something that remains foremost in Mazwai’s work, both as a connecting thread and as the guiding context of specific songs.

Songs such as Abenguni speak of the protective shroud of our immediate genealogy, but they also zoom out to track our migratory paths throughout the continent. So when Mazwai speaks of Kush, Kemet, Azania and Nubia almost as if they are interchangeable, it is because she is trying to connect pasts, presents and futures as existences that can transcend interruptions.

The songs, transformed sonically, enter fantastical dimensions, but they also hold their own as historical documents. In a sense, what was happening on Saturday was a return into the music, a metaphor for the larger project the singer was asking us to participate in — that of continuing the search for ourselves.

Transkei Moon, for example, enters the realm of a collective sojourn broader than its geographical confines suggest, and Ndilinde becomes less a love song than an expression of generational compassion.

By insisting that the songs be opened up, slowed down, dubbed out, Mazwai imagined them as chambers, alcoves, sanctuaries, bodies of water. And, as they do every December 16, December 24, December 31 and January 1, as referenced in Collective Amnesia the masses were submerged and were baptised, connecting their dead selves to their living cells. After all, what are our artists if they cannot be our compass.