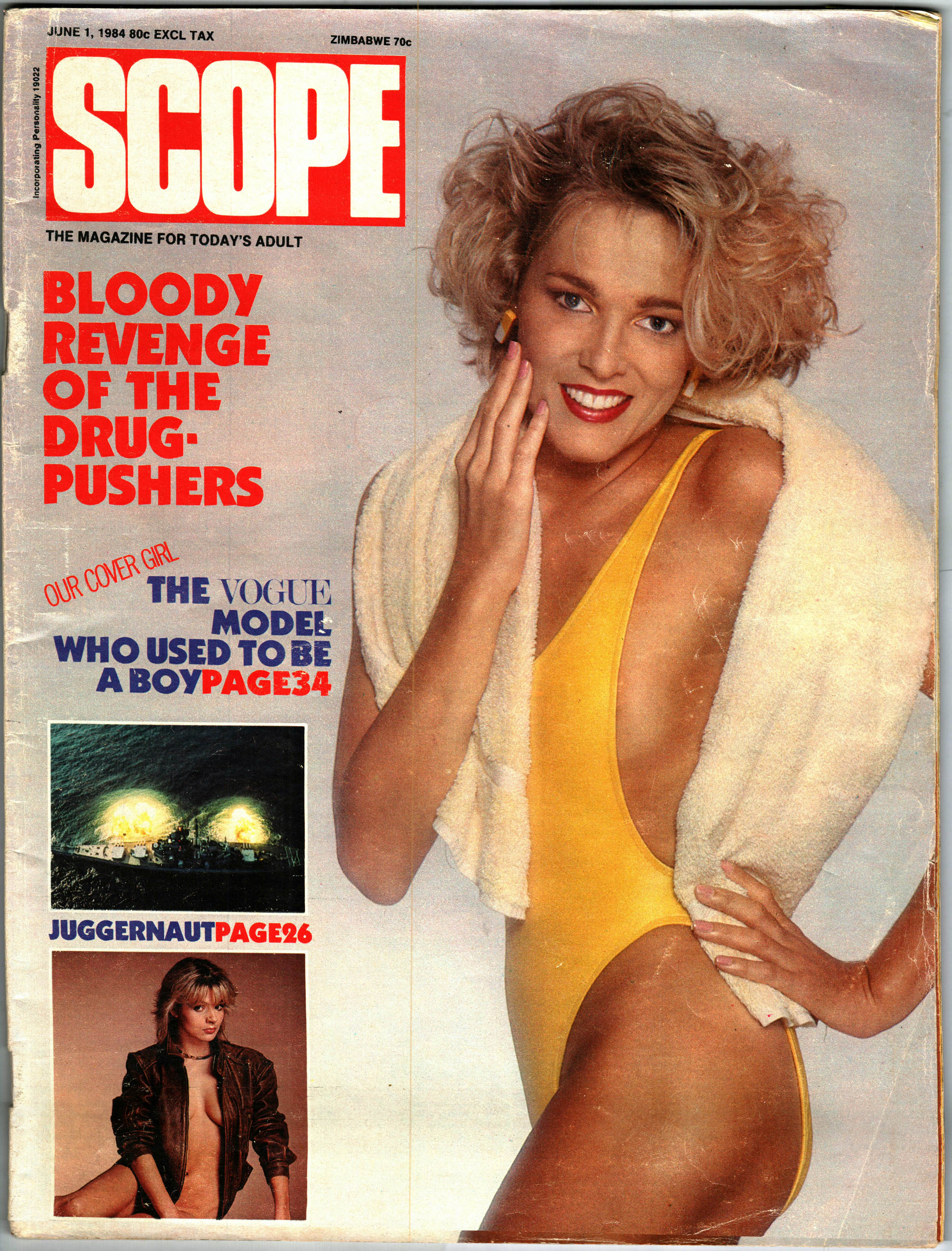

Just another pretty face: Lauren Foster, who became the first trans woman to be honoured as a Woman of Empowerment by Variety, doesnt agree with brands that use trans models to seem cool or because its trendy. (Courtesy Lauren Foster Facebook)

“God, I sound like Burt Reynolds or something. Thank God my boyfriend’s not here. I would have terrified him,” Lauren Foster says, letting out a hoarse, hearty laugh.

It’s the day after the opening of Art Basel in Miami, Florida, and the 61-year-old has been “partying till five this morning”.

Now the director of the University of Miami’s lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer clinic and a trans rights activist, Foster says she was thrown into activism “kind of begrudgingly”.

What really catapulted her into the public eye was something she did more than willingly: stripping off her clothes and stepping in front of the camera for her “provocative” editorial spreads in Scope, the now-defunct South African weekly magazine.

Born in Durban into a “very accepting family”, Foster says she “had a very blessed childhood”.

“They paid for my surgery and always encouraged me to be who I am. I started my medical transition when I was 16, but my parents always allowed me to dress however I liked from a very young age,” she says.

Modelling was something she always wanted to pursue. “Especially because people would always say: ‘You’re so pretty, you should do this.’ And it was kind of like a dream, which I guess I kind of manifested.”

Given her break into the industry by a friend who worked at a modelling agency, her first shoot was a five-page editorial spread for Scope in 1980.

“They didn’t know I was trans. It was a very successful issue, because our shoot was very provocative. It had me kind of topless, with my hands over my breasts, posing with my boyfriend at the time, who was also a model.”

After the “revolutionary, very risqué and talked-about” story was published, Foster was outed as transgender.

“It was then that they approached me and were like: ‘Oh, we would love to do a story on you.’ But they kinda gave me no option. They said: ‘We can do the story with your blessing and [you could] tell us the whole story or we are going to go ahead and do it without you.’ I was advised to do it with my blessing because then I could control the content.”

About whether she had any apprehension or fear about coming out to the world as a trans woman, Foster says: “No, not at all. But then again, this was before the internet. So maybe people did say nasty things, but I never heard it. Nowadays, with the internet, people could be abusive or nasty. Then, it wasn’t a thing. You just heard rumours. I was so oblivious to [any possible backlash]. I was never self-conscious because of my parents always saying to me: ‘This is who you are; live your truth.’”

Monique Walker, who was born intersex, was another South African model who graced the pages of local magazines such as Scope, Stag and Bunny Girl.

Unlike Foster, her childhood was “horrible. My mother used to call me ‘that thing’ and ‘freak’ and those things. I never knew what motherly love was like towards a child. I never knew what it was like to be held by my mom like the rest of the kids. I had to watch how the other kids were being hugged and kissed, and I was pushed aside,” she says.

Leaving home at the age of 16, Walker entered nursing. When she was 17, she “did corrective surgery to make it more aesthetically pleasing to myself and others”.

It worked. “Various photographers and agents approached me. Initially, I was a bit horrified by [posing topless]. You know, growing up in conservative South Africa, I didn’t think I would do that. But the money was great.”

Of her initial shoots for Rapport’s back page and Scope, Walker says: “I was a bit nervous, but felt a little powerful.”

For “maybe 27 years” she enjoyed a successful career as a model, appearing in European and American editions of Penthouse, Playboy and Hustler magazines.

But, says Walker, “nobody ever knew what I was”.

“I’m just a woman to most people. I never informed people of who and what I am. You writing this story and bringing it to the world, people will hear something about me they’ve never heard before,” the 58-year-old says, adding: “But I’m proud.”

For Jabu Perreira, of intersex and trans rights organisation Iranti.org, increased public visibility for intersex people “has become a necessity”.

A report published by the organisation found that intersex people face “a multiplicity of discriminations” emanating from “social and religious norms which seek to ‘correct’ their bodies in accordance with binary norms”.

“Visibility has contributed to creating information,” says Perreira. But with increased visibility there has also been increased commercial expediency on the back of the transgender experience — something Foster takes issue with.

“People will hire you, write a story and put you in a show nowadays because its trendy. Like: ‘Oh wow, look, we’ve got these trans girls in our show.’ And it’s to garner more press and to have your brand seem cool. But I have a problem with that. I think you should be hiring me because I’m gorgeous or look good in your magazine.”

Foster, who this year became the first trans woman to be honoured as a Woman of Empowerment by Variety magazine, lets out another hoarse laugh, adding: “But I am maybe a bad trans person, because I’m not ‘ra ra ra, I’m trans’. I really don’t want people to hire me because I’m trans. I’m not a fetish. I’m not a trend.”

Although transgender and intersex people enjoy more legal protections than they did in the days when Foster first entered the public eye, she says: “I’m glad my story broke then because the week after that story came out, it was lining the bottom of a birdcage somewhere or in some dentist’s office. Two weeks later, it was forgotten about.”

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian