Mamelodi magic: The township, which is home to a number of artists, musicians and activists, is cradled by the Magaliesberg originally named after Mogale, leader of the Po people. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

‘When the apartheid government moved people here,” says musician and activist Azah, “I don’t think they knew they were putting people in the best space, energetically.”

Mamelodi’s majestic location, which Azah speaks of, is something apparent to the eye but mercurial to the spirit.

Cradled by the Magaliesberg mountain range (named after Kgosi Mogale of the Po people), which stretches from the far side Rustenburg in the west to Bronkhorstspruit in the east, Mamelodi is the proverbial land of the gods. Its rich contributions to South African cultural and political life struggle to be contained by the mountain range and have spilled out into the world.

Its name is shrouded in legend. Apparently it was named by its first mayor, Hesekia Mathibe Pitje, in 1962 who, in protest against the name Vlakfontein, decided to honour former Transvaal republic president Paul Kruger and his penchant for whistling. In a twist of fate, the township’s residents would spend a lifetime erasing Kruger’s relevancy in the naming of their new abode.

“When I was growing up, it was the times of black consciousness, where art was appreciated stukkend, stukkend all over Mamelodi,” says poet and playwright Themba ka Nyathi from his stoep in Mamelodi’s section D5. “You could set up now [at 2pm] and say you are having a poetry session. At 4pm that hall would be full. People used to be creative. They used to write poetry, they used to sing songs, it was rich.”

A large part of that reputation, Ka Nyathi says, has to do with the revolutionary figure of Geoff Mphakathi, who opened up his home to a generation of artists and agitators.

“Bra Geoff was an institution,” he says emphatically. “A lot of us emerged out of Bra Geoff’s house. We got books there. We got guitars there. Poetry. That’s where the group Dashiki — you know the group Dashiki Poets, yabo Lefifi Tladi? It emerged from there … If you grew up in Mamelodi and were an artist, you had to go there.

“Apparently he was working for the American Embassy, so he was able to get what he could get, organising us books and things. We’d go to his house and, quite literally, invade it.”

That ka Nyathi refers to Mamelodi’s reputation of creativity and resistance as a sort of bygone era is troubling, and it is a sentiment expressed repeatedly during my two-day sojourn to parts about the township.

Opening up for musicians Madala Kunene and Mabi Thobejane at the Village in Mamelodi West this past Sunday, malombo musician Thabang Tabane spoke of the township’s reputation as a matter of hearsay.

“From what I read and hear from my father and his friends, it was special,” he says, sitting in a car to the right of the stage. A kwaito version of Busi Mhlongo’s Yehlisan’ Umoya Ma Africa blasting from the concert sound system almost overpowers our conversation. “I think I came of age during the decline. The culture now is one of self-preservation. The youth don’t have enough platforms so they get discouraged.”

If there was indeed a golden age in Mamelodi, what on earth could have brought it on and ushered in its demise?

“I think the consciousness went hand in hand with apartheid,” he muses. “That thing of trying to avoid what they foisted on you by counteracting it. Now it’s just clumsy in many ways and many people don’t know what they want.”

On a sweltering Tuesday, in Sikhakhane Street, Bobby Nkambule, a contemporary of Philip Tabane’s, walks around shirtless in the shade of his courtyard. He and a friend, Ruben Koloti, add coats of white paint to a rough-surfaced wall. His mate, Mabi Thobejane, slowly rises from a nap.

“Mams, like before, is becoming independent again,” he says, contextualising the effect of 25 years of democracy. “It is a free enterprise place. Omunye nomunye bavuka bazenzele manje, [Everybody is in do-for-self mode now],” says Nkambule.

From the outside looking in, one may assume that the first impulse is to open a drinking hole, as several bazaars and business lanes are populated by these.

“People sell clothes, they cook for themselves, others run nightclubs. Some are small, but you never hear of incidents like robberies and so on,” he clarifies. “You might hear of it on the odd occasion but it’s not common.”

In the days of yore, he says, there was no shortage of moguls with cash to spare splashing it on supporting bands. The gigs, he says, would be these all-night raucous affairs. “Makuphela ibioscope kwakukhwelw’ e stage ’til daybreak [After the bioscope, we’d hit the stage]. Koloti says the culture of investing in the arts has faded, not only for musicians but for sports too. Perhaps the benevolent black tycoon has been replaced by the government bureaucrat.

Anecdotally, it is still a place “with a strong community spirit”, at least according to musician and Mamelodi native Vusi Mahlasela.

“It’s still there, that spirit, at least to people that know each other. But things are changing and the more outside people arrive, the more people keep to themselves. Take Moretel River, for instance. The people who have lived here for longer know not to settle close to the river because it would flood and you’d find pots and clothes there. But now other people have placed themselves there. It’s like, ‘Let’s grab ourselves some land’.”

An apt descriptor, for Mamelodi, says Mahlasela, is that the place is “like a country unto itself”. Its residents speak about it like a latter- day Timbuktu, a place of learning for the likes of Miriam Makeba and Desmond Tutu and a place of deadly sacrifice for others, such as activists Florence and Fabian Ribeiro.

“People started protesting in Mamelodi as early as 1948 against the rondavel system,” says historian Aubrey Mogase, whose self-published book Mamelodi: Reflections of a Lifetime was released in April this year. “The rondavel system was a housing scheme that whites wanted to build for the urban population … So it was considered suitable to fit the urban housing to a ‘traditional Bantu village’.”

On reflection: Author Aubrey Mogase has written a book about the history of the township outside Pretoria. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

From then on, there was the 1956 home-brew strikes in protest against the government’s plan to monopolise the production of home-brew, squeezing out the livelihood of informal brewers in the township.

“This community was very close-knit,” echoes Mogase. “The forced removals of the 1940s and 1950s brought a lot of people together from Eersterust, Lady Selborne, Riverside. [Because of the shared trauma], people treated each other as family. They looked after each other’s kids. The community existed as one big family.”

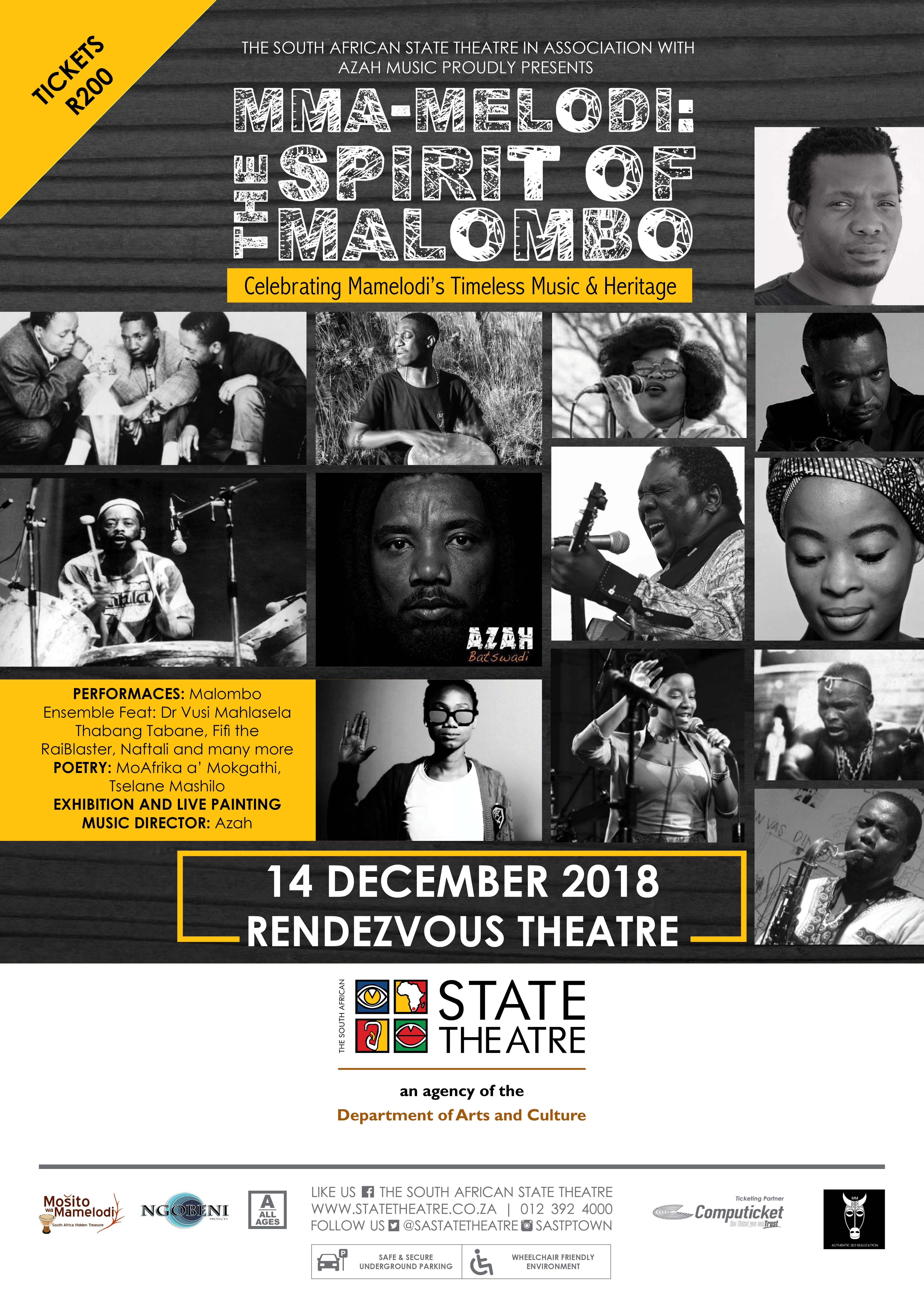

Today, the artists who have inherited all of this move with that same family spirit. Azah, who is directing the conceptual concert Mma Melodi: The Spirit of Malombo, draws on the talents of his contemporaries. Artists such as Mo Afrika ’a Mokgathi and Tselane Mashilo, Mahlasela, Tabane, Naphtali of the Royal Family, Ncamisa, Fifi the RaiBlaster, are all, in some way, the spirit children of malombo and the heirs to that tag: Pitori ya mahlanyeng [Pretoria, where the mad ones live].

It demonstrates the oblique, ahead-of-the-curve nature that Mamelodians carry themselves with. It’s where the collectors gathered, trekking their imports across town. It’s where to dika meant to perfect a soft-shoe shuffle. It’s where the slang was always current, but mostly, it’s where young and old learned to defy death.

Mma melodi: The Spirit of Malombo is at the State Theatre’s Rondezvous on December 14. For more information, visit statetheatre.co.za