Lornaand Leonard Joseph and Denis Petersen are snapped with their minder Togo in about 1959. Photo: Bronwyn Anderson

Imagine being in your local museum, but the people represented on the walls don’t look like you.

In South Africa, for many of us, we don’t have to imagine it and a new exhibition that opened this week at the Durban Art Gallery adds its voice to the growing chorus of work correcting the error of representation.

Proclamation 73 explores memory, erasure and home by drawing on the family album as a source of history. In this way, the exhibition does the radical work of re-entering under-represented peoples into history.

Issued in 1951, Proclamation 73 was the law according to which Indian people were categorised as a subdivision of the coloured group. It was issued by the apartheid government under the Group Areas Act and forced removals followed.

Initiated by social researcher Zara Julius and curator Chandra Frank, the exhibition draws on photographs of weddings, beach days, ballroom dance contests and street portraits, which are exhibited alongside photographs of the aftermath of forced removals. The project aims to challenge static racial categories and to investigate how categories such as “coloured” and “Indian” were used as anti-black tools.

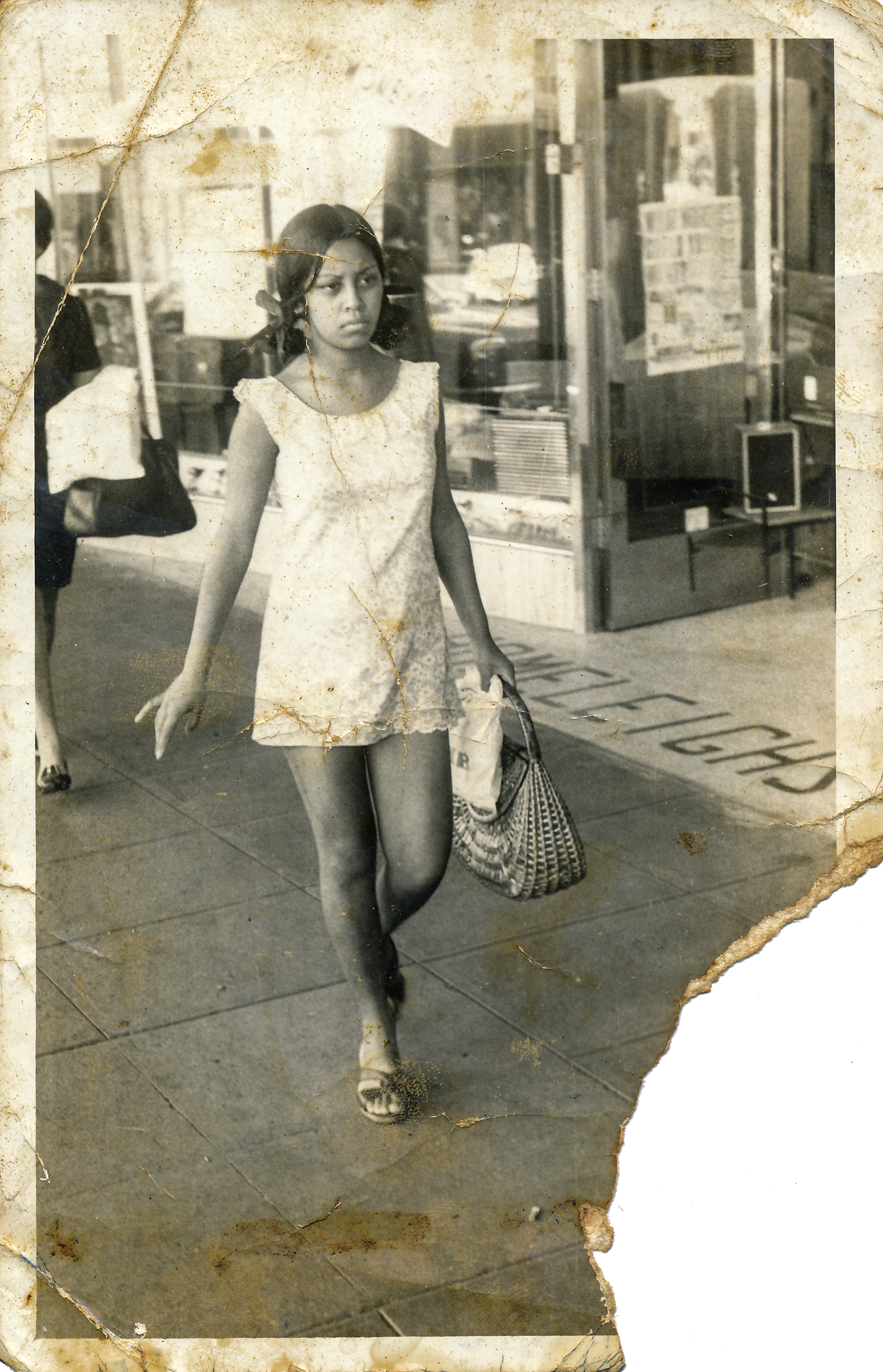

Desiree Henneberry (1969)

The project focuses on neighbourhoods in Durban North and Durban South that were designated for coloured and Indian people. Frank’s father is from Chatsworth and Julius’s mother’s family was initially in Cato Manor, which links them both closely to the exhibition.

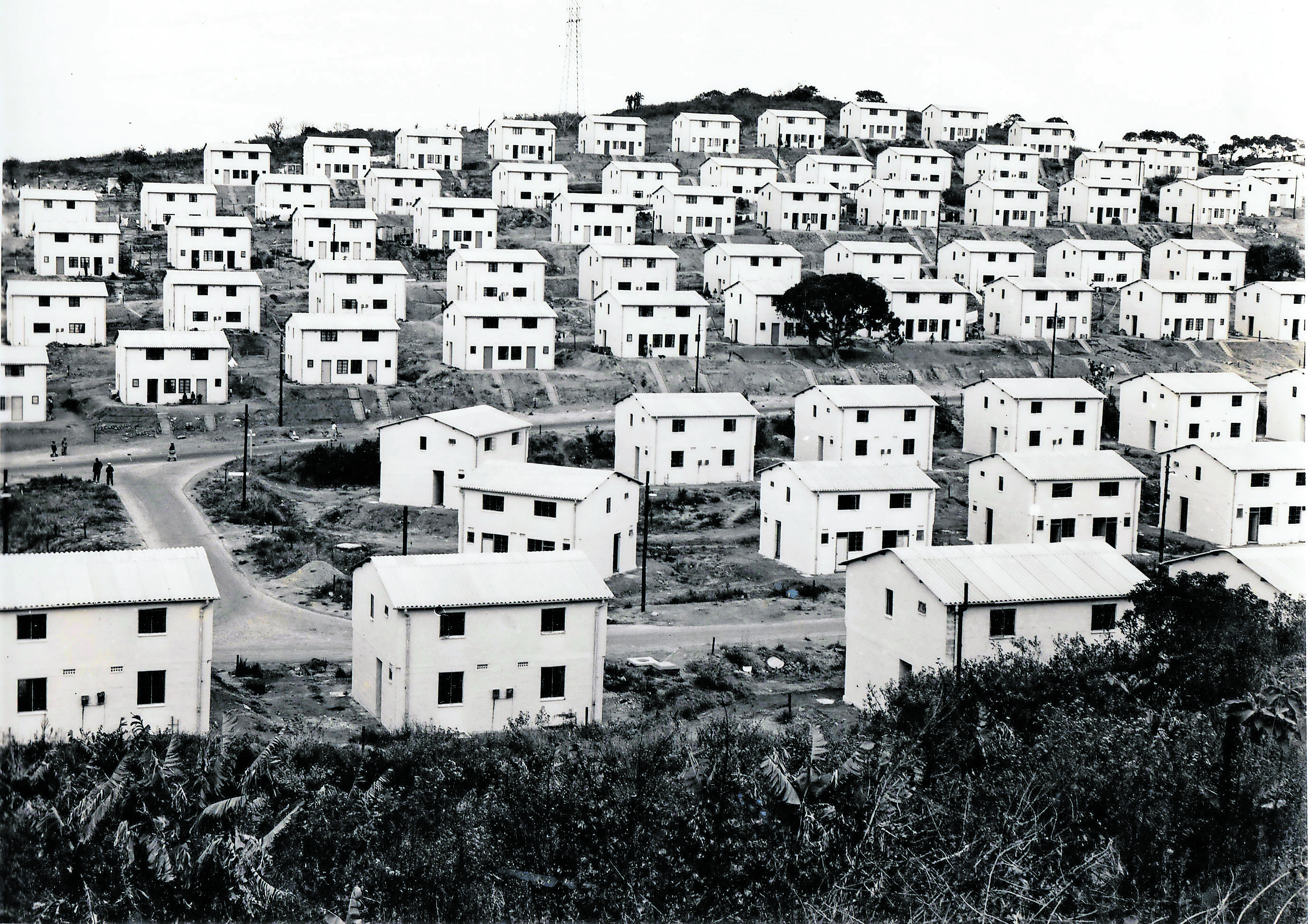

Community album: One of the collected photographs is of Chatsworth homesin July 1964. Photo: Old Court House Museum

Speaking before its opening this week, Julius explains: “Both of us were really interested in our family’s experiences around forced removals. For me, personally, I was interested in Durban experiences around colouredness, because, I think, when people talk about coloured identity, it’s quite situated in Cape Town and the Western Cape. People don’t really know the narrative around Durban coloured identity. I use the term ‘coloured’ in inverted commas because it’s obviously a very contested term.”

The project was interactive and the creators put out a call for family photographs of homes, gatherings and communities from before 1994. Although people were responsive, Julius says that getting them to scan their photographs proved difficult and the curators had to change their approach.

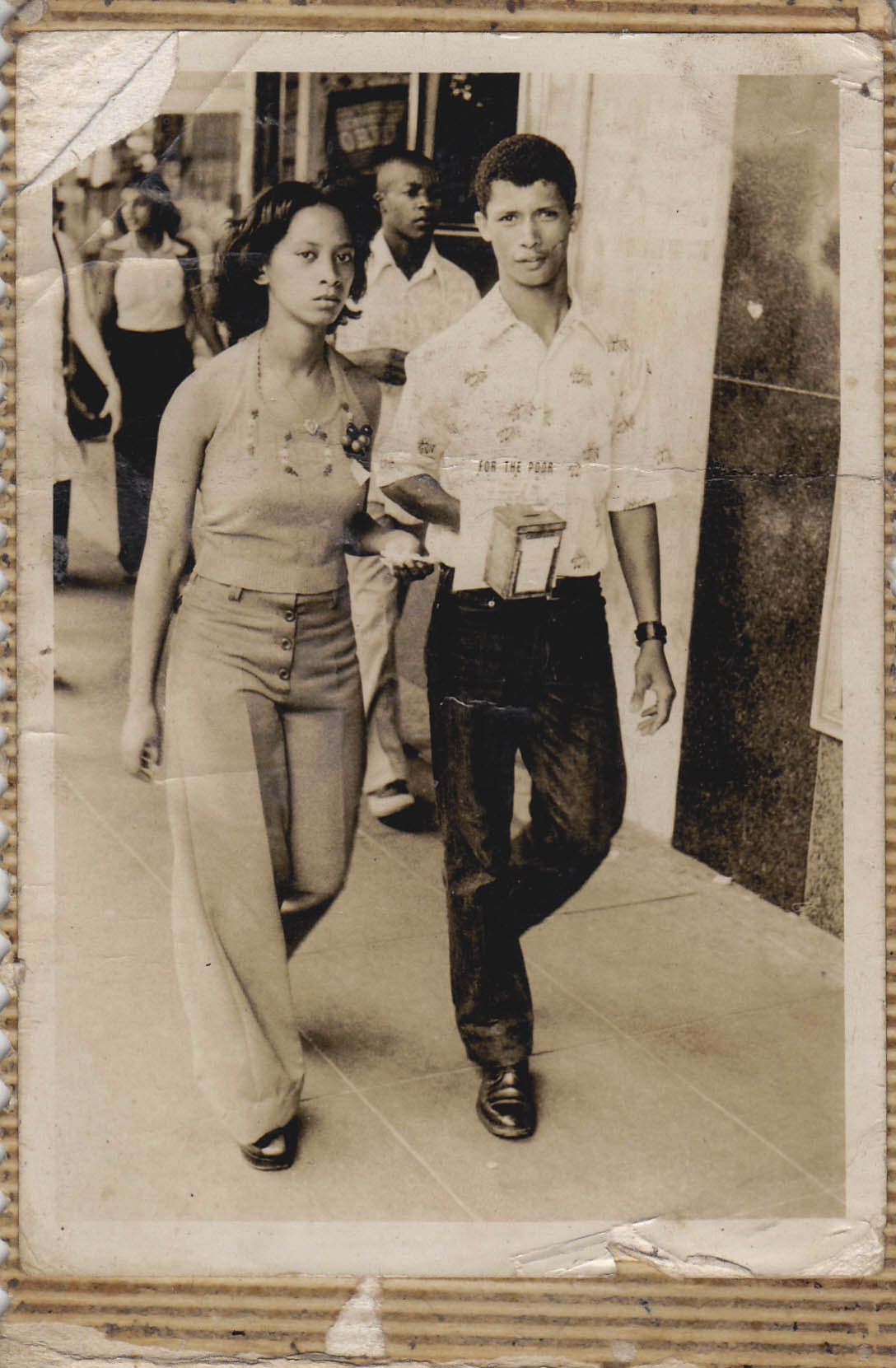

Joyce Williams and Anthony Solomons (1975)

“Durban was difficult to activate. What I ended up doing was making house visits with my scanner and my computer.”

One of the aims of the exhibition is to challenge notions about race and space in Durban.

“The idea around this term ‘coloured’ is super-fixed in the South African population’s imagination. Imagine the experience between being from the Western Cape and being from KZN [KwaZulu-Natal] and then being from Gauteng. And that’s obviously got to do with the fact that the term ‘coloured’ was a label placed on people with varying different cultural experiences and ethnic backgrounds. What was important for me was to have a more complicated conversation around this term ‘coloured’.

Esther Moyce and her daughter Dulcie Moyce (1924)

“Not every coloured person speaks Afrikaans, for example. In Durban, the cultural proximity is way closer to Indian experiences. The other thing that was important was to think through how the term Indian moved from a national identity to a racial identity. It was only in 1951 that the term Indian became a racial identity.”

The two histories, those of coloured people and Indian people, are often read independently, but the exhibition presents them together, intertwined but different.

‘Mrs Green’ and children (date unknown)

What was the thinking behind this?

“To show, quite frankly, how absurd racial classification was and continues to be. People’s lived experiences are way murkier than we are led to believe. Some parts of one family would be classified in three different ways, you know? There are people who have some cousins classified Indian and other cousins classified coloured and then one uncle who managed to get himself classified as white,” Julius says.

The exhibition is a greater community family album, which forms a collective memoryscape, as both a physical exhibition and a digital archive. Digital copies of the photographs will be donated to the KwaMuhle Museum so that there’s more content and visibility about the issue spread throughout the city.

Apart from addressing limited personal knowledge about ancestries, projects such as Proclamation 73 address erasure in historical narratives. In particular, South African recorded history has deliberately erased us and where we come from. If we don’t do this for ourselves, it simply won’t happen. Did Julius experience a similar emotional reaction to this process?

“Totally. Going through the archives and trying to see what does exist, and then realising, ‘oh, nothing exists’. That is really shocking. And then what does exist is a collection of photographs of women, girls cleaning and sewing at an orphanage. It’s quite hectic that that becomes the narrative in Wentworth.”

I return to thinking about the violence of forced removal. The story of having your family forcibly removed is one many can relate to. It’s one I have heard over countless Sunday lunches in my own home in Cape Town, and displacement under the Group Areas Act is a narrative that resonates with millions of people all over South Africa.

When the apartheid government issued Proclamation 73, the point was not only to separate white people from the rest of the population, they also wanted to create communities distinct from those of black people. This stratified form of racialised oppression was reflected by and continues to be reflected by the anti-black sentiments expressed in coloured and Indian communities.

“It’s so tricky, because, on the one hand, we’re trying to bring our communities in and trying to say, ‘Hey, we need to be more active in taking charge of our stories and our narratives’. So we’re trying to bring communities in without alienating people, but at the same time also trying to educate and push our communities to be better.

“So, yes, the exhibition does address anti-blackness. We speak to the gaps in the archives in the exhibition. We have kind of tackled it that way,” says Julius.

The gaps in the archives is a phenomenon seen in many families. The older generation is often quick to point out their European great-great-grandparent, but have little know-ledge about their indigenous lineage.

Julius says: “As an example, a lot of homes from my grandparents’ age would have photos of their white grandfather or father from the UK [United Kingdom] somewhere, but there would be no photograph of, say, his black partner. So the archive is always limited. We have to look into the gaps of the archive.

“An example would be my great-grandfather, a white man from Ireland, who came through and had several children with several different Zulu women. There’s a photograph of him, but no photograph of my great-grandmother. The question becomes: Why is there this missing link? It raises questions of anti-blackness and erasure of blackness.”

Given the brutal effects of gentrification today, does Julius see any parallels between the forced removals of the Groups Area Act and what’s going on in places like Woodstock and Bo Kaap in Cape Town now?

“Oh, completely. I was thinking through the protest that happened like, two weeks ago, where citizens in Bo Kaap were trying to stop a crane from coming on to this site and they were met with a really insane amount of police brutality, considering it was, like, 20 aunties praying.

“And I was thinking like the Bo Kaap somehow survived forced removal, and survived apartheid. But will it survive neocolonialism and white capitalism? There’s totally a link between forced removals and gentrification.

“I don’t know if you know about the concept of ‘hauntology’, where things from the past haunt the present. That’s kind of how I see the gentrification in Cape Town.”

Proclamation 73 is a not-for-profit project in partnership with the Goethe-Institut South Africa as part of the Goethe-Institut Project Space. The exhibition will be on at the Durban Art Gallery until February 15