Censured: The 3.5m statue of Leonard Peltier, sculpted by Rigo 23, was removed from American University. Rigo 23s Ripples Become Waves exhibition is touring the United States to draw attention to calls for Peltiers release from jail

Two years ago, a sculptor called Rigo 23 hewed a 3.5m statue of artist Leonard Peltier out of redwood, with a base exactly the same size as a prison cell — six feet by nine feet (2X3m). Peltier is a 73-year-old Native American activist who has spent the past 41 years in jail for killing two FBI agents, Jack Coler and Ronald Williams, in 1975. But many believe he was a scapegoat and that the authorities have never convincingly proved he was the one who pulled the trigger.

The statue travelled from California to American University’s Katzen Arts Centre in Washington, DC. Peltier’s son Chauncey said the statue honours his father as “a symbol of the native struggle for self-determination”.

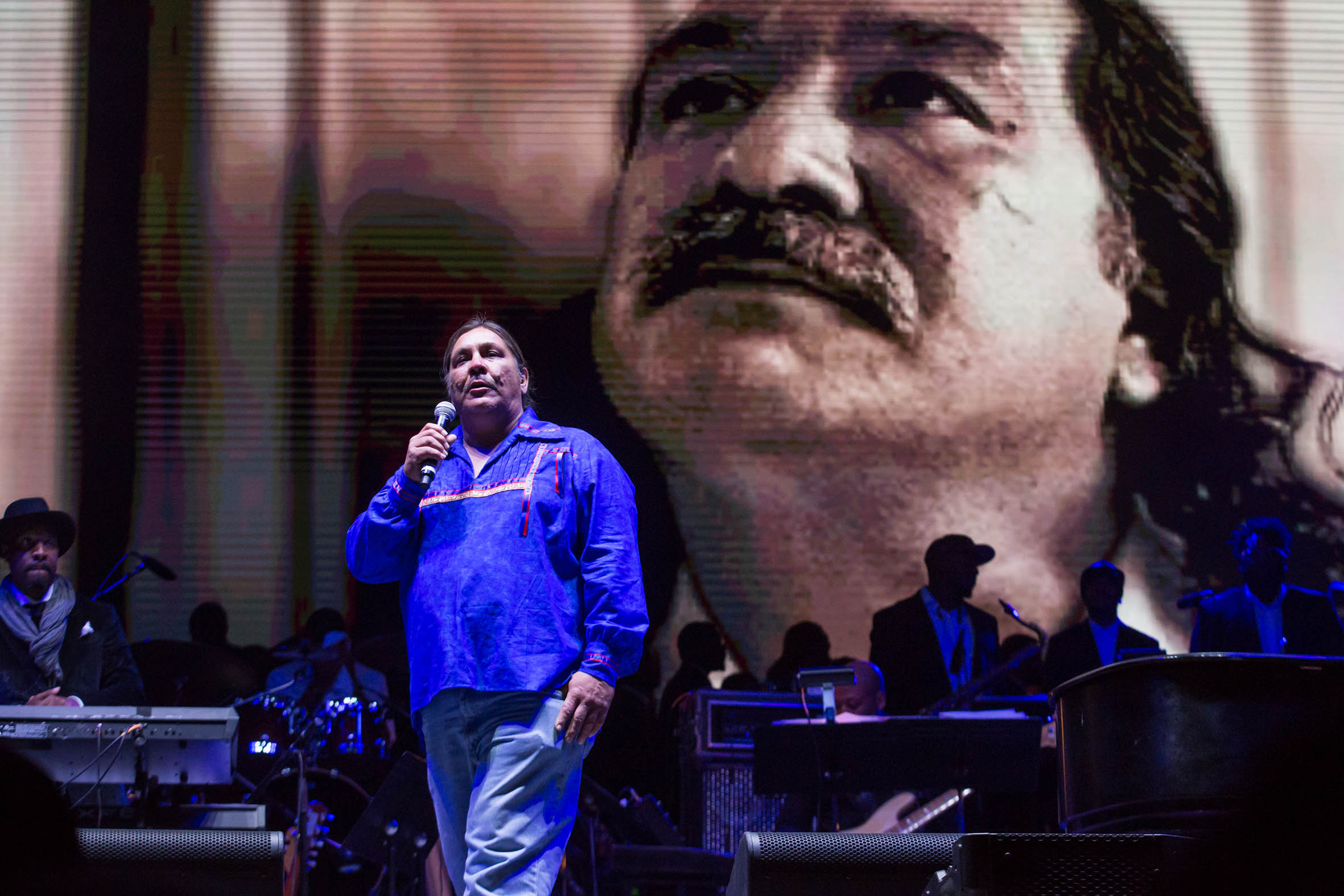

Chauncey Peltier, son of Leonard Peltier,speaks at Harry Belafonte’s Many Rivers festival.Photo:Cheriss May/NurPhoto

A student at the university wrote on Twitter that “a 9-ft [3m] cop killer is right in front of my dorm”. The FBI Agents Association asked the university to remove the statue. Neil Kerwin, then the university’s president, wrote in protest against the NGO’s call. The artwork was removed in 2017.

Support for Peltier’s release has spread outside the US, and organisations such as Amnesty International are questioning his trial.

Free him: A rally was held in support of Leonard Peltier outside the US embassy in Moscow in the 1980s. Photo: PZubkov

Peltier’s paintings, depicting scenes of traditional Native American life, were removed from the Washington department of labour and industries in 2015. This was mainly in reaction to complaints from FBI agents Edward Woods and Larry Langberg, who operate the blog No Parole for Peltier Association who have been instrumental in blocking the numerous appeals for Peltier’s parole or clemency.

Old ways: Leonard Peltier paints scenes of traditional Native American life

The man Woods and Langberg believe is a cold-blooded killer was a member of the American Indian Movement (AIM), which was formed in the late 1960s to advocate for Native American rights. AIM has led protests, inspired cultural renewal, co-ordinated employment programmes and monitored police activities, particularly on American Indian reservations.

Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, where the shooting of Coler and Williams took place, is one of the poorest areas of the US and has been the site of several confrontations with the authorities. The Wounded Knee Massacre took place there in 1890, in which up to 300 Native Americans died. In the Wounded Knee Incident in 1973, AIM instigated the seizing and occupation of Wounded Knee town, which led to a 71-day siege.

Peltier, a metalworker by trade, was on the reservation to help to reduce ongoing violence between political opponents in Pine Ridge in 1975 when the fatal shooting occurred. Coler and Williams were pursuing a vehicle (after the theft of a pair of cowboy boots) when they died in a hail of bullets.

Peltier features on the Robbie Robertson album Contact from the Underworld of Redboy. In the song Sacrifice Robertson talks to Peltier over the phone, and then runs their conversation over the soundtrack. When Peltier quotes the prosecutor who presided over his case, who said it was unclear who pulled the trigger, but “somebody has to pay for the crime”, this stuck in my mind.

Robertson says in a 1998 Rolling Stone article: “Of the three people who were charged [for killing Coler and Williams] the other two were found not guilty by means of self-defence. When that happened, the authorities said, ‘Hold on, what’s happening here? Who do we have left?’ Leonard was the one who hadn’t been put on trial. They hand-picked the judge, they moved his trial to another state — he was a sacrificial lamb.” Several other artists have featured Peltier on their albums and Robert Redford narrated a documentary about his sham trial. Concerts dedicated to his clemency, which featured artists such as Pete Seger, Harry Belafonte and Jackson Browne, have been in vain. His numerous appeals received support from Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, among others. In 2001, when it was rumoured that Bill Clinton was going to pardon Peltier, about 500 FBI agents protested outside the White House.

Peltier, who is now in poor health, is not the longest-serving prisoner on record. Wikipedia lists 18 men who have been incarcerated for more than 60 years: 16 from the US and two from Australia. Charles Fossard was imprisoned for 70 years, for killing a man; he died in an Australian jail at the age of 92. Mandela, the world’s most famous political prisoner, spent 27 years in jail before his release in 1990. Jafta Masemola, a cofounder of the Pan Africanist Congress, was also in jail for 27 years. He died in a car accident a year after his release in 1989.

In one of history’s cruel twists of fate, Palestinian Nael al-Barghouti was imprisoned by the Israelis for 33 years and then released in a prisoner swap in 2011, only to be rearrested in 2014. Guinness World Records says Al-Barghouti, now 61, is the world’s longest-serving political prisoner.

But Peltier deserves that title — if he is a political prisoner and not a cold-blooded killer.

What constitutes a political prisoner

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (re)defined the concept of what constitutes a political prisoner in 2012 as follows:

A person deprived of his or her personal liberty is to be regarded as a ‘political prisoner’:

a. if the detention has been imposed in violation of one of the fundamental guarantees set out in the European Convention on Human Rights and its Protocols, in particular freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of expression and information, freedom of assembly and association;

b. if the detention has been imposed for purely political reasons without connection to any offence;

c. if, for political motives, the length of the detention or its conditions are clearly out of proportion to the offence the person has been found guilty of or is suspected of;

d. if, for political motives, he or she is detained in a discriminatory manner as compared to other persons; or,

e. if the detention is the result of proceedings which were clearly unfair and this appears to be connected with political motives of the authorities.