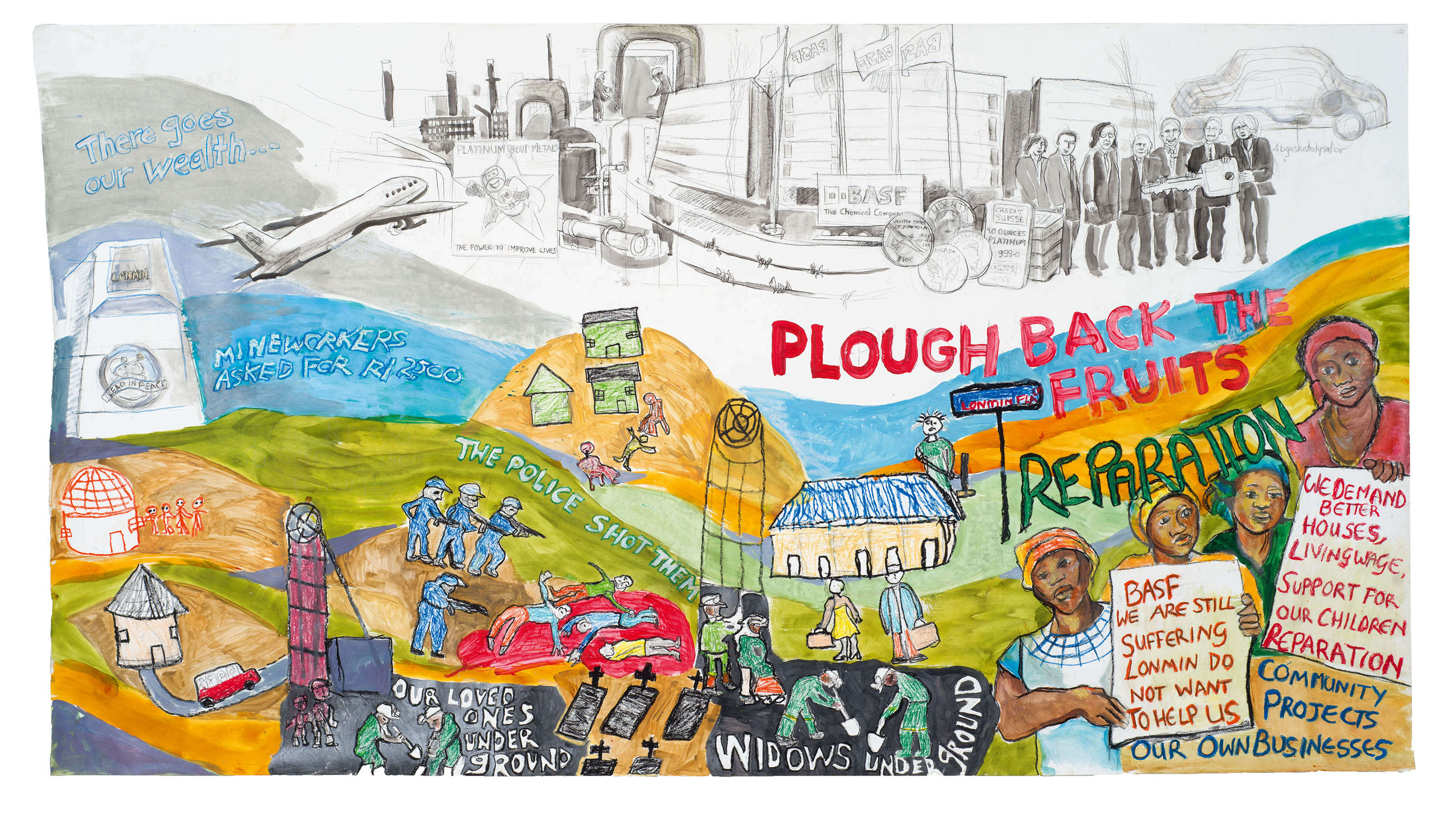

Hard-hitting: The Widows of Marikana (above), an artwork that appears in Business as Usual, depicts the price of capitalism shattered families.

Business as usual after Marikana: Corporate power and human rights (2018) edited by Maren Grimm, Jakob Krameritsch and Britta Becker (Fanele)

When Bishop Jo Seoka addressed the annual meeting of BASF shareholders in 2015 in Mannheim, Germany, write Maren Grimm and Jakob Krameritsch, “You could have heard a pin drop.” This was because “none of what Seoka was addressing had even been mentioned in the [German] media or by BASF itself. The connection between BASF, Lonmin and the Marikana massacre was new to the majority of people present.”

Seoka, the former Anglican bishop of Pretoria, had been involved in hearing the strikers’ grievances and following up on the aftermath of the massacre. Those present in Mannheim were the 600 or so shareholders in BASF, the German multinational and the largest chemicals producer in the world. It had a long-term agreement to buy the bulk of the platinum produced by Lonmin, the mine at the centre of the “wildcat” strike that was crushed in August 2012 by the South African police, leaving 34 dead.

Widows call out the companies associated with Lonmin mines. Photo: ZZ Nkaneng

What Seoka was trying to get through to the shareholders was that, in the aftermath of the massacre, the company had done almost nothing to help the survivors and the families of the deceased, despite BASF’s carefully developed image as a socially responsible and caring corporate entity. Many were not even aware of BASF’s three-decade relationship with Lonmin.

BASF’s then board chair, Kurt Bock, made mealy-mouthed noises: that it was hard for BASF “to judge from a distance”, BASF had too little information, and basically “BASF regarded Marikana as a domestic problem for South Africa”. The report of the Marikana Commission of Inquiry into the massacre had not yet come out, which was one excuse used by Bock. But, even once it had, BASF did all it could to avoid taking any responsibility for the conditions that led to the strike and the massacre or for making any restitution to the victims’ families.

In some kind of fairness to BASF, it must be said that the World Bank, which had a stake in Lonmin worth about R200-million (through its investment arm), had visited Marikana to monitor conditions, but produced a whitewash of a report in which everything was just hunky-dory.

Business as Usual After Marikana details the historical background to the massacre, going back a long way into the history of South Africa’s mining industry, as well as showing what activism has taken place since Seoka’s speech to try to at least embarrass BASF into taking some responsibility. The book itself is surely part of that campaign, funded as it is by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, and produced almost as though it was a coffee-table book, with plenty of pictures in full colour, printed on glossy paper — all 450 pages of it.

An art work in Business as Usual After Marikana (Fanele Publishers)

So it is a bit ironic, too, as an artefact: an organisation funded by the German government produces an expensive and good-looking piece of activism directed at one of Germany’s largest companies, which you would have thought was bound by German government and international rules for social responsibility. Perhaps this is the only format in which, they believe, BASF shareholders and German regulators will take in this information.

The book certainly provides that information and, in its many essays, the analysis to go with it. It traces German (and Swiss and Austrian) links to South African extractive industries back through the era of sanctions against apartheid, when companies such as BASF stepped into the breach left by disinvesting American companies such as IBM, which supplied and maintained the apartheid state’s computers, for one thing. For another, IG Farben, which developed synthetic-fuel technologies for the Nazis during World War II, was a vital supporter of Sasol during the sanctions era.

The company trading in the platinum-group metals that was bought and absorbed by BASF in 2006, Engelhard, was led from 1960 by Charles Engelhard Jnr, a key figure in the South African Foundation. This lobby group was an association of businesspeople, based chiefly in the United States but with global tentacles, devoted to making apartheid look not so bad so they could keep doing business with South Africa.

A major irony in this tangled story is that it was late-1970s environmental activism, particularly that aimed at reducing carbon emissions from cars, that led to the boom in platinum sales (used in catalytic converters in diesel cars) and palladium (non-diesel cars). Once it became obvious that this was something that would be legislated, in the interests of the environment, it was clear this would be a good market to get into.

Ironically, too, Lonmin as a platinum-mining company grew from entities that were once part of Lonhro, which under its flamboyant boss Tiny Rowland was the prime example of a neocolonial extractive capitalism. Lonhro showed how business interests and those of the African post-independence state could be interlaced.

Lonmin, after all, at the time of the massacre, had a black empowerment scheme as mandated by South Africa’s post-apartheid ANC government, in particular that of then-president Thabo Mbeki. The leading beneficiary of this was Cyril Ramaphosa and his companies; Ramaphosa, who had once been a leader of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), then became a staggeringly rich businessperson as black economic empowerment was rolled out, and now — in a final irony — is the president of South Africa.

The former NUM leader was not well disposed towards the rival union driving the strike of 2012, Amcu (the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union). He called the striking miners “dastardly criminals” and urged strong action — not that he would necessarily have endorsed the deadly force unleashed by heavily armed police officers on August 16 2012. He had chaired Lonmin’s transformation committee, which managed not to spend most of its R665-million commitment to decent housing in the 2007-2011 period.

In the same period, as Patrick Bond writes, more than $600-million (about R8.3-bllion at today’s rate) in profits and dividends went to shareholders, and Lonmin shifted about R1.3-billion in revenues to tax haven Bermuda so it would be taxed less in South Africa. In 2016, BASF Metals Ltd, the London arm that buys Lonmin’s platinum (and sells much of it, after processing, to Volkswagen) made a profit of R480-million. The appalling living conditions of Lonmin miners and their families, besides the demand for a wage hike, were key parts of the unhappiness that led to the strike.

Those living conditions have barely improved since the massacre, and that’s despite the commission’s report and the continued activism of various involved people, as detailed in this book.

Lonmin promised more in 2014; in 2017, there were protests about lack of delivery. Now Lonmin has been bought by Sibanye-Stillwater, which aims to use its smelter capacity to generate revenue and to downgrade its mining operations, which have become too costly. Many of Lonmin’s 28 00 employees face retrenchment, and that’s without reckoning with the depredations caused by labour-broking, work on limited contracts and other means by which such companies externalise their costs. Women, in particular, as the “invisible backbone” of the mining industry, remain unpaid and uncompensated, just as they did in the worst days of the migrant-labour system.

Here, then, is a case study of corporate entwinement with government policy and practices, in the interests of extractive neocolonialism.

It shows how a façade of social responsibility can disguise rapacious profit-seeking for a very long time, and how this kind of charade of capitalism with a human face can explode, in very nasty fashion, when it comes to the crunch.

BASF, alongside all the other corporate and government participants, should be ashamed. Can a glossy publication such as this help it find its conscience?