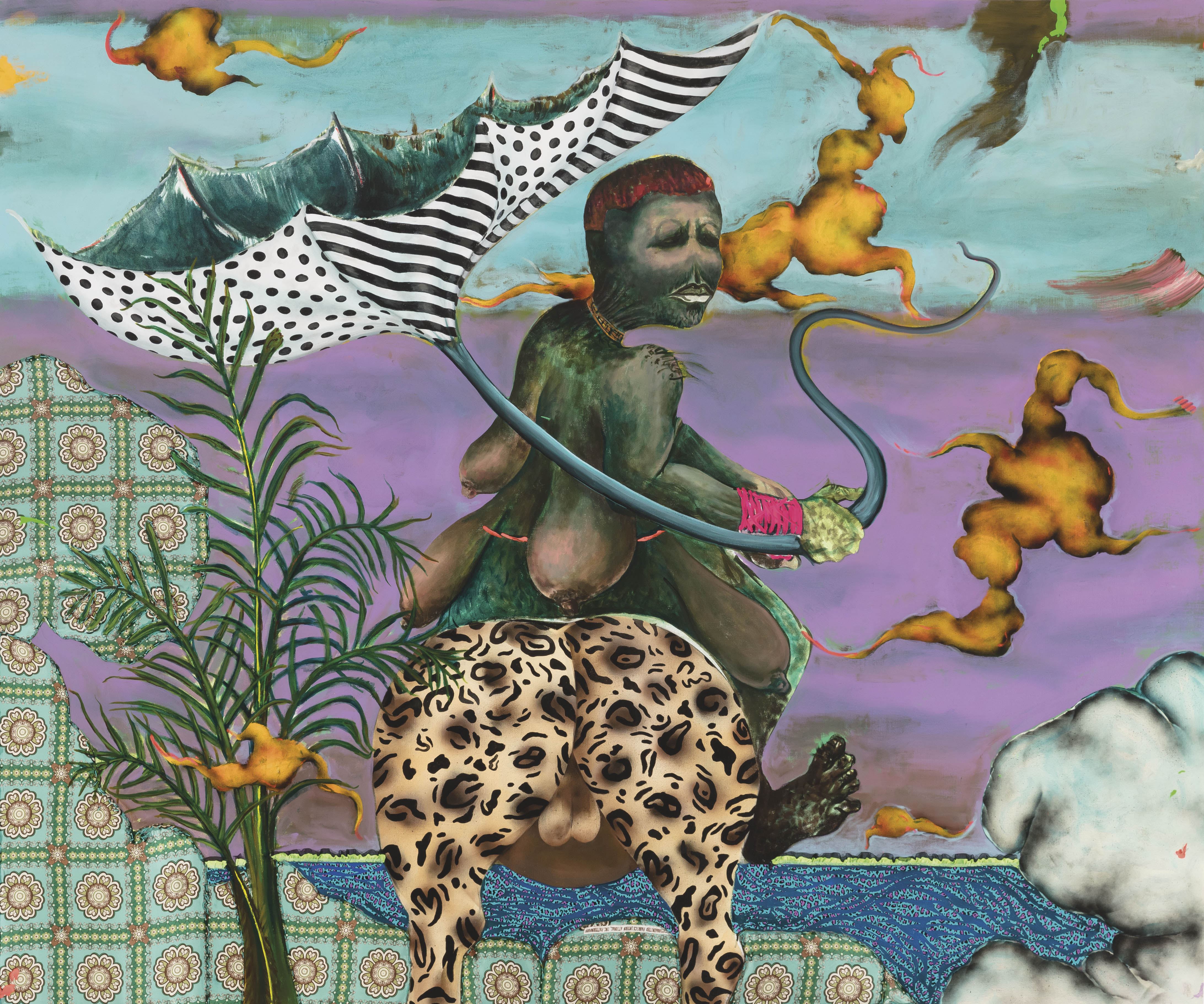

Afrofuturist: 'Seekers of Light' (2018) from Simphiwe Ndzubes solo exhibition 'Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas'.

Magical realism and Afrofuturism, as modes of conjuring alternate universes, are en vogue in today’s cultural practice. So much so that it might seem as though one is out of touch with the times if one exhibits a disinterest in it.

Of course, that, in itself, is ironic. If anything, such genres circumvent linear time — particularly the narrative of progress. Their deferral, delay, suspension or quests for another time tend to tamper with the narrative of progress, but it is hardly plausible to assume that alternate worlds are “discovered” by the sheer work of miracles and magic. More so, it is equally untenable to think “miracles” of the 1990s will deliver us out of the morass they’ve “created”.

The exhibition by Simphiwe Ndzube invites a contemplation of this. Although this is his fourth solo show, Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas is his debut exhibit at the Stevenson Gallery in Cape Town. Prior to this, he’s had solos in What If The World Gallery (2016), Los Angeles (2017), and at Shanghai (2018). These achievements barely scratch the surface of the 29-year-old University of Cape Town art graduate’s accomplishments, which include the prestigious awards he’s claimed in his burgeoning career, most recently the Tollman award for the visual arts in 2016.

Marvellous flight: Goddess Nanana (2018) forms part of Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas.

Critic and scholar Ashraf Jamal prophesied that Ndzube is “to be a rising star … a reminder that Africa is not merely a landfill for a wasted imagination, defunct ideals or ruined fantasies, but a thriving and talismanic force field for a further circulation and recycling of a now further-transmogrified waste”. Jamal sees in Ndzube’s work “a joy in sadness — that allows for greater wonder”.

From this alone, one would swear that Ndzube also possesses the celestial dexterity of walking on water. After all, one could ask, what would be the use of this kind of work if it pulled nothing out of the hat?

When asked what he draws from this tradition, Ndzube said: “I seem to be obsessed with things transitioning and inhabiting multiple dimensions of being and becoming. Magical realism affords me a way to tap those spiritual connections — between life and death, the obscurity of time, the grotesque and uncanny, but always with the foundation in the physical and sociopolitical world of those existing in the margins.”

Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas enables this magical trip to the artist’s chosen destination he calls Mine Moon. Doesn’t the fixation with discovering or inhabiting “other” planets in contemporary expression resemble latent fantasies of the colonial hangover?

Although I am fatigued by the prevalence of alternative worlds, be it heaven or Wakanda, Uncharted seems to be on to something. It expands from the artist’s repertoire of existential perversities. In these painting-sculpture hybrids, Ndzube constructs an unintelligible universe inhabited by ungendered creatures.

The narrative echoes Matata Tsedu’s 1980s short story Forced Landing, in which a UFO filled with colonial “strangers of colour” lands on Mars under the pretext of seeking to replenish its food supplies.

In Ndzube’s show Mungu settlers have turned Spirit natives into gravediggers, although this explanation isn’t immediately offered. But it’s this subtle narrative arc of colonial conquest that motivates the show. Clearly, the fact that reality seems magically forfeited isn’t to say that these non-familial worlds have nothing to say about “reality”. As a result, Mine Moon acts as more of a prognosis of our historically unexceptional status quo than it does as an echo of the more prevalent pie-in-the-sky dogma.

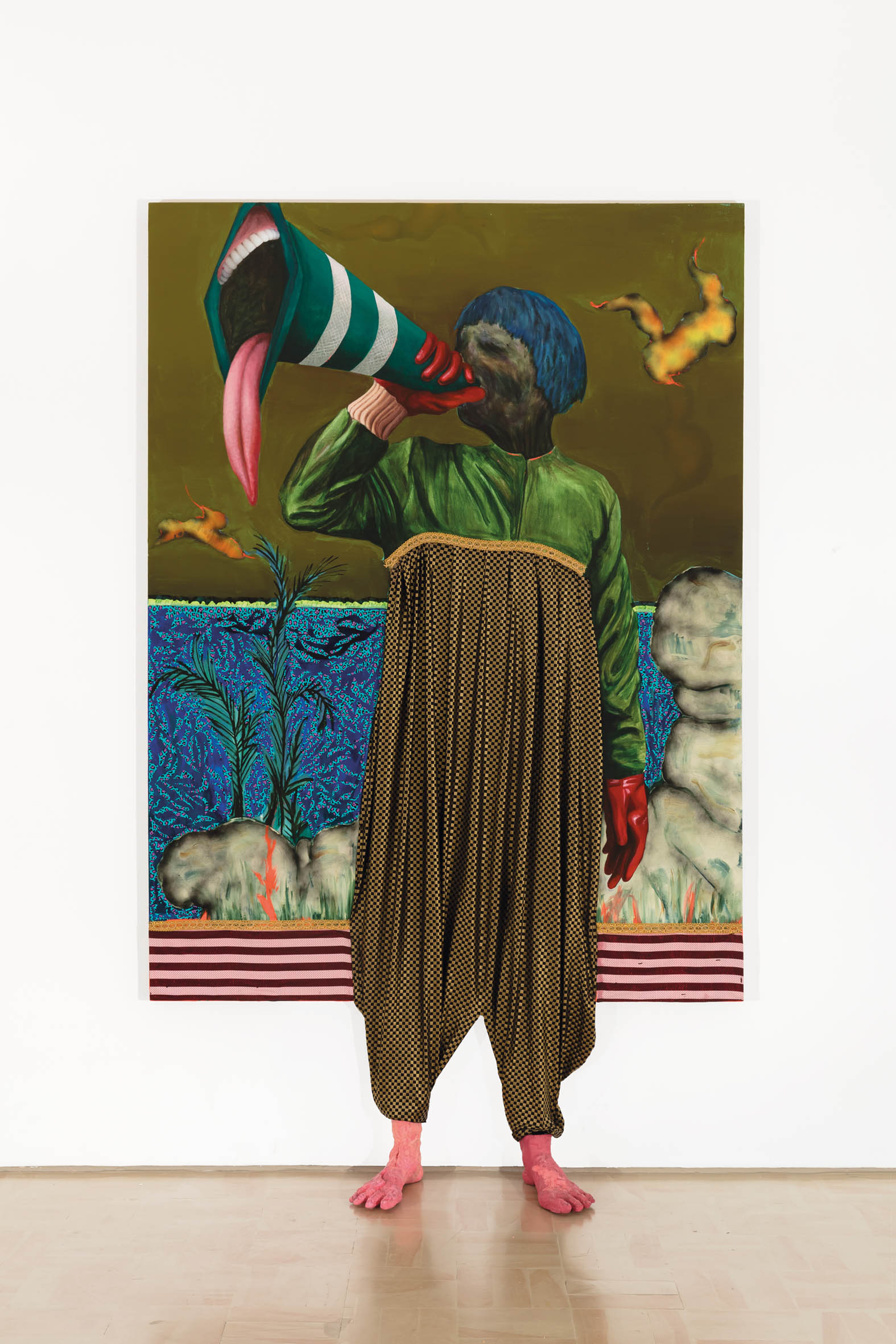

This paradoxical use of prepossessing strangeness — the worlds that aren’t quite knowable, humans that are not quite human, or creatures (wearing gumboots) that are unidentifiable, random sand dunes placed about on the gallery floor, paintings that aren’t quite sculptures or installations, and so on — are ubiquitous strategies in science fiction. Its subversion of ordinary life uncannily circumvents the fetishism about ordinariness prevalent in some corners of the arts. Reality plays a cameo role in the interstices of myth and magic, only to subvert itself. It is foundational in so far as what we see as only familiar.

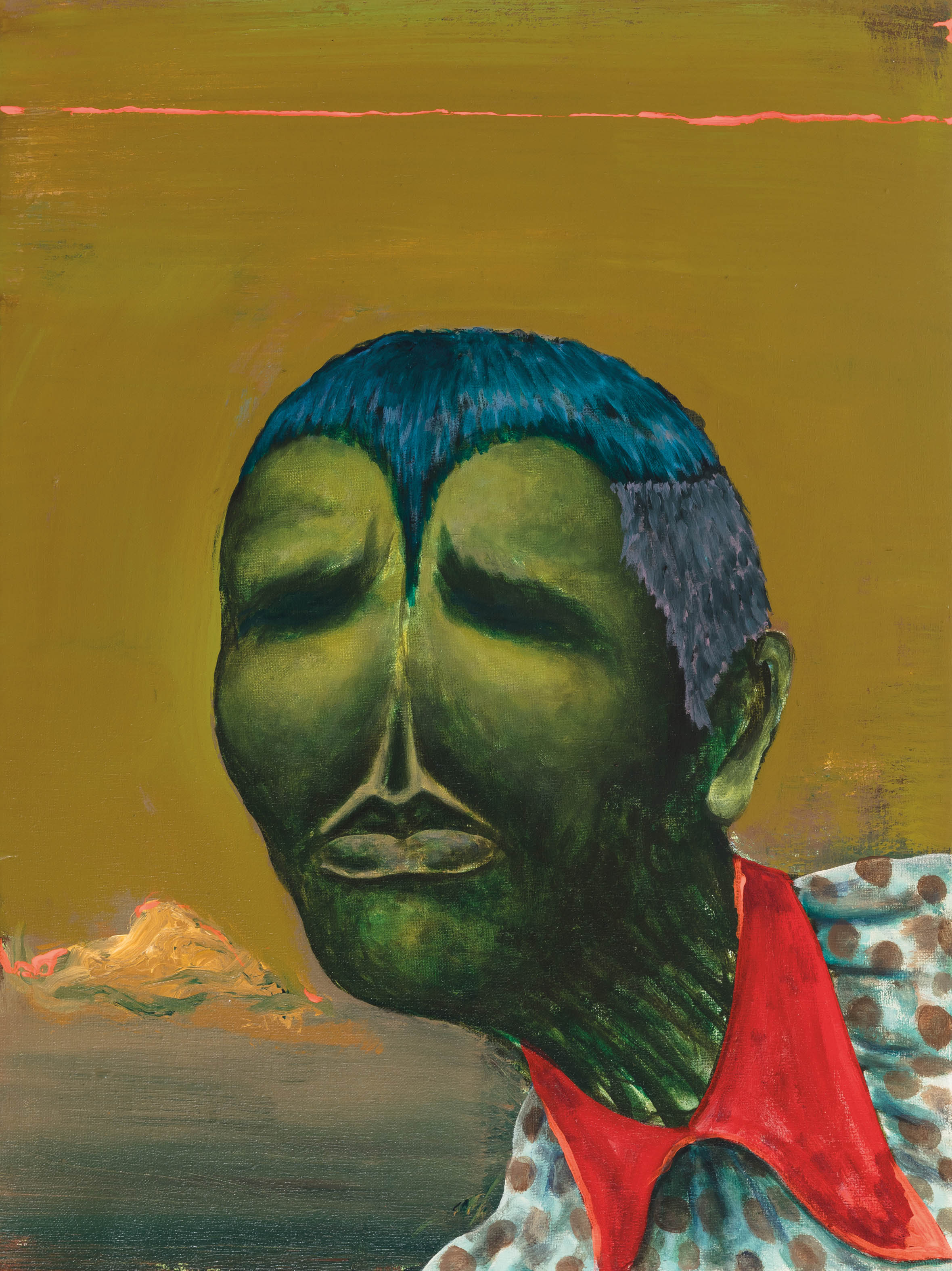

Gorogo: The Dictator Returns From The Dead (2018) Simphiwe Ndzube

This body of work is relatively new compared with Ndzube’s previous works. We’ve seen his faceless flâneurs and Penny Penny Guy Homo sapiens. Of course, some traits or signature moves are continuous — Ndzube’s predilection for the sartorial, grotesquerie and colour are unyielding. And by now we know he’s distinguished himself as part of the young artists to whom colour is like clay to a master potter.

As always, it feels neither forced nor spontaneous. This is despite a few rather unsatisfactory moments in his acrylic portraits in this show. It is, however, his obsession with faciality, or lack thereof, that gives his fabulist painterly tales a perennial strangeness.

If, as idiom says, we are where we are, then the physiognomic peculiarities of his figures are in concert with their surroundings. These are nobodies of nowhere. On one side, the perennial trademark of facelessness, for better and for worse, elaborates on the geographical invalidness of Mine Moon. On the other hand, it instantiates how Mungus and gravediggers exist as fictional constructs of the prevailing colonial order.

A figure reminiscent of the doom-heralding, ghostly, childlike creature in the horror film The Ring dominates Uncharted. As in the film, we can’t see its face.

On the other side, we’ve seen a similar hair motif in many of Athi-Patra Ruga’s hirsute performances of his characters Beiruth and Afro-Womble, and even in The Future White Women of Azania Saga. In the works Mpunguzo: Chief of the Spirit People, Malandela and the Gravedigger, Bhazuka: Michael Jackson of Mine Moon and others we see variations of this hirsute character. Curiously, though, in Malandela, at the bottom right of the piece, it appears Ndzube chops visual phrases, as it were, directly from Ruga’s repertoire. The references to his balloons (albeit deflated), the elaborate wigs and the sprouting foliage are subtly present here. This is probably a subtle salutation.

Portrait II: The Spirit People (2018) Simphiwe Ndzube.

In The Orator, a figure both fashionable and comical literally steps out of the painting and yells into his loudhailer. True to Ndzube’s predilections, instead of seeing sound ideograms issuing from the hailer, we see the orator’s teeth and tongue jutting out as if it were a scene from Jim Carrey’s The Mask.

The Orator (2018) Simphiwe Ndzube.

This kind of perversity, in which the imagination leaps or invents new worlds, was critical for mid-20th-century literary movements. The philosopher and writer from the island of Martinique, Réné Ménil, characterised it as bringing the marvellous into real life. But today marvellous flights into fictive worlds easily facilitate all kinds of deracinated utopias, alternate worlds in which we can temporarily find comfort.

Ndzube doesn’t construct an elsewhere from which we can enjoy temporary reprieves. Knowingly or not, he instead offers enough room for critical scepticism about this trend. Overall, Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas places itself outside of the commonplace cherry-picking blind optimism of this genre.

Uncharted Lands and Trackless Seas runs at the Stevenson Cape Town until March 9