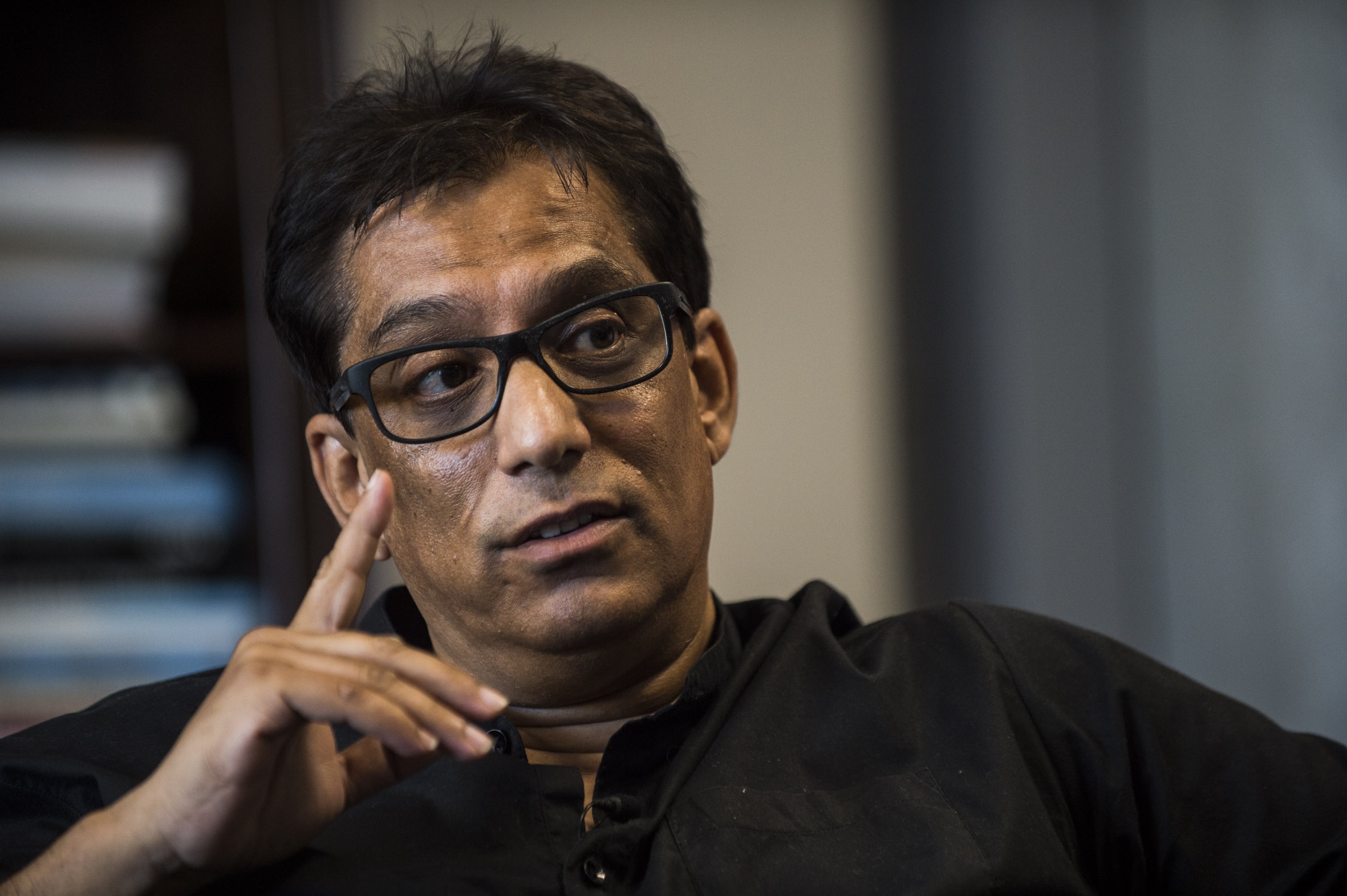

When pressed about various controversies surrounding his businesses, Iqbal Survé insists he is simply misunderstood and has done nothing wrong. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Seated in a plush leather armchair in his office in the silo district of the V&A Waterfront in Cape Town, Iqbal Survé is more reticent than his recent public utterances.

He’s been embroiled in controversy following reports that he had sought to mislead the Public Investment Corporation (PIC) over the viability of its investment in Ayo Technology Solutions. The Sunday Times claimed that the PIC invested R4.3‑billion in a 29% stake in the company (or R43 a share) when its real value was 15 cents a share. Furthermore, the Sunday Times reported that Survé used the R4.3-billion PIC investment in Ayo as “his own personal piggy bank”.

Survé responded with characteristic bluster to these allegations, accusing the paper of publishing a “highly defamatory” article.

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian this week, his words appear more measured, more controlled. But he is not cowed, he says. More than that, he is determined to continue doing business as he has.

“When I was a doctor for 10 years, it was nice to make a difference on an individual level, but as a businessman you have the opportunity to make a difference on a macro level and that’s what drives me,” he says.

His desk, overlooking Table Mountain, is tidy except for the stacks of paper towering over parts of it. There are confidential documents everywhere in the office, we are told, by way of explanation when we are prevented from video recording the interview. The photographer is also not permitted to take pictures of anything in the office but a seated Survé.

It is an impressive office.

With the window opening up views of the mountain on one end, the rest of the room is furnished with what, even to the untrained eye, are exemplary pieces of fine Asian carpentry. The wall across from Survé’s desk is fitted with a dark wood bookshelf and two ladders to navigate its floor-to-ceiling reach. A diverse collection of books and trinkets dot the shelves. Some books reference Nelson

Mandela, a particular favourite of the doctor, though he may not have been his patient. Many are coffee-table art books, like a collectible from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. From another stack, the cover of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam looks out across the room, a silent invocation to whoever looks its way. On the other end of the room, on another shelf, the erotic novel 50 Shades of Grey stands out.

Survé certainly is an interesting man.

He insists he is just misunderstood, maligned by people who fear his commitment to causes he describes as “left of centre”. He sees himself as an outlier in business circles, the “underdog” with none of the appetite for the fast cars and private jets that he says are the natural inclination of similarly successful businesspeople.

“I do what I think is in the best interests of the country, sometimes against my own interests in doing that, but maybe I’m brave, maybe I’m foolish to actually articulate on behalf of people who don’t have the opportunity to articulate their needs,” he says.

He parades his convictions well, does Survé. And that emphasis on his personal virtues in the face of intense scrutiny of his business practices may be his undoing.

When he talks about what he believes to be a campaign against him, driven by racist forces in business and the media, he appears far removed from reality.

But make no mistake, Survé is not an idiot.

He is uncannily shrewd. You do not amass a fortune as vast as his without some cunning.

And you certainly do not get away with skirting the boundaries of propriety and governance in business without some savvy.

But when he is pressed about the various controversies in his dealings with the PIC, he points instead to racist structures underpinning business in South Africa. It is a convenient deflection mechanism, especially when few black people would disagree about the reality of structural racism in South Africa. But his polemic does not answer the very serious questions put to him.

When he does eventually get around to it, he insists that neither he nor the companies associated with him have done any wrong. He says his businesses have been built with a high standard of ethics that have actually disadvantaged them. When fishing quotas are distributed, for example, or government advertising spend allocated, he gets the lesser share because of his high ethical standards.

He does, however, concede that he has a personal relationship with Dan Matjila, the outgoing chief executive of the PIC. “I consider him a friend, that is the first thing,” he says. He rejects any assertion, however, that it is precisely that friendship that influenced the PIC’s decision to invest in Ayo, the IT company in which Survé holds an indirect stake.

“I think it is insulting — number one, to Dr Matjila. I think it is an insult to our management teams. I think it is an insult to myself because we pride ourselves on our excellence, on black excellence,” he says.

Survé goes on to defend Matjila as a “brilliant technocrat” who he believes has been a casualty of politics — and the Guptas.

“I think it is despicable what the Guptas tried to do to him by framing him with this issue in relation to his girlfriend,” Survé says, of a report that said Pretty Louw, alleged to be Matjila’s girlfriend, had indirectly benefited from R21-million in funding from the PIC.

“It was a classic strategy to undermine this poor, innocent man.”

In Survé’s assessment of the world, correcting the narrative of the country to reflect these kinds of truths about Matjila, for example, is crucial. But his attempt to do that at Independent Newspapers has instead resulted in the group being remade in the image of Survé.

He refutes this, of course, insisting his editors have “autonomy”.

“A few weeks ago, I had a conference call with the editors in our group and it was so funny because I hadn’t even met two of the editors. I was embarrassed actually. Sometimes I haven’t spoken to editors in months.”

In the acquisition of Independent Newspapers, the PIC loaned Survé’s Sekunjalo Investments R1-billion. Survé has been unable to keep up his commitments to the PIC, a result, he says, of the turbulence in global media commerce. But, he says, he has not leaned on the PIC, as a shareholder, to help prop up the Indy, which runs at a R300-million annual loss. It falls to him to fund the loss, he says. And he indicates that Sekunjalo seeks to do right by the PIC.

So, to Survé, everyone critical of him has been unfair.

“There are powerful interests that don’t tell the story as it is in general — and not just in media — in multiple ways, and maybe I’m an underdog person, and that may be part of the challenge that I face today is that, ‘as successful as I am’, I am not part of the establishment.”

The establishment, he says, are people who fear him and regard what he represents as an affront to their own chances of continued prosperity. But he denies that he can even be seen as a participant in an alternate establishment.

It is quite a feat for a billionaire businessman who hobnobs with government ministers at the State of the Nation address in Parliament while using the front pages of his 18 newspapers as a personal mood board to claim that he is not part of the establishment. But in Survé’s mind the establishment has a particular guise, which excludes him.

“I hate bullies, I really do. I hate the establishment for monopolising the economy,” he says. “I don’t play golf, I am not controlled by anyone in Stellenbosch or Sandton.”

Again and again, Survé references his links to politicians today to his participation in the struggle against apartheid, but firmly denies that his friendships with Cabinet ministers have been a currency in itself.

“I still live a very simple life,” he says.

He talks about himself as a simple man who has been unfairly maligned, a man who eschews Rolex watches for a simple Fossil watch bought on the streets of New York, preferring the company of family and friends to the conventions of the golf course. He insists that his aim in business is not to amass a fortune, but rather to build a platform from which to promote the development of black people in South Africa.

But Survé’s methods, through a platform he has created in the name of the upliftment of black people in general, even in his own telling, remain unaccounted for. So too do his own gains. He says his profits are funnelled to philanthropic causes close to his heart. And his strength is derived from the fact that he represents something more than himself. In his telling, he is the embodiment of the project of transformation. The reason Independent Newspapers editors will splash his statements on their front pages is that they wholeheartedly share his vision.

When he reads out loud a birthday message to him from an Independent Newspapers staff member he is beaming. That is where he draws his security from, the knowledge that he is able to surround himself with people who are unflinching in their loyalty.

What Survé’s success in business has bought him is the ultimate luxury — a sense of reality that is uninterrupted by opinions, or facts, that contradict his own. Surrounded by his staff scurrying about the office in the Waterfront, hanging on to his every word, he is still alone in himself, with just his thoughts, his ideas — and his hubris.

Listen to a podcast of the interview here: