People queue in makeshift camps following past threats of xenophobic attacks in South Africa. Today, rescinded health department memos requesting foreigners pay in full for healthcare have sparked a national debate. (Fredrik Lemeryd)

COMMENT

Directives recently issued by the national and Gauteng health departments requiring foreign nationals to pay in full for healthcare at public facilities weren’t only a threat to public health, they may have been downright illegal.

Walk into a public hospital, and you may be asked to fill out a form stating just how much you earn. That’s because many services in the public sector are billed for on a sliding scale based on a means test: You pay what you can for the treatment you need. At least in theory.

In mid-January, a national health department circular reportedly instructed clinics and hospitals to begin billing foreign nationals the full rate for public health services. Low-income refugees, the memo said, would be the sole exception and would be means tested, Business Day reported.

Only Gauteng passed these instructions onto its clinics and hospitals, specifying that all non-South Africans other than documented refugees should be charged full fees for all services including emergency treatment, maternity care and “basic health services”. The national health department has now said that the circular should have never gone out.

Speaking to Business Day, Gauteng Health MEC Gwen Ramokgopa said “the province had aligned itself with national policies” but had withdrawn its circular to public facilities.

As a public interest law organisation, we believe that Gauteng’s circular was unlawful in that it had the potential to withhold previously available services from patients, contravened the National Health Act and could have led to violations of people’s constitutional rights. It also threatened to derail progress towards HIV targets contained in the country’s latest national plan that require 90% of all people to know their HIV status and 90% of those to be on antiretrovirals.

Section 27 of the Constitution says that everyone has a right to have access to health care services, including reproductive health care services and that no one may be denied emergency medical treatment.

What does this mean? Here’s a break down of who is entitled to what in South Africa’s public sector.

1. Who is entitled to free healthcare in South Africa?

Section 4(3) of the National Health Act provides for certain free health care services for people who don’t have medical aid. It does not limit access to these services based on nationality or immigration status, meaning that these services are available to all, South African and not; documented and not.

It says:

- Everyone is entitled to free primary health care services at government facilities. This means that clinics are free to all;

- All women are entitled to free abortion at government facilities. Under South African law, anyone can terminate a pregnancy up until 12 weeks for whatever reasons and between 13 and 20 weeks if the pregnancy endangers the woman’s mental, physical or socioeconomic health;

- All pregnant and breastfeeding women and children under the age of six are eligible for free health care services at public clinics or hospitals.

Until a health minister publishes conditions to the contrary, this is the law that applies. In the future, if this happens, a health minister won’t just be able to impose whatever conditions they like. They’ll have to show their proposals take into account the free services already available and how changes would impact access to health care services and the needs of vulnerable populations such as women, children, the elderly and people with disabilities.

A 2007 national health department directive also guarantees free HIV and TB care and treatment to anyone regardless of status.

2. What health services do foreigners pay for?

Refugees, asylum seekers as well as undocumented migrants from Southern African Development Community (Sadc) states including Lesotho, Mozambique and Zimbabwe who need hospital care — should be treated like South African citizens. That means they’ll have to take the means test given to South Africans to determine how much they have to pay for hospital care.

Undocumented people from countries outside Sadc who attend hospitals — except pregnant or breastfeeding women, children under six and women seeking an abortion — are expected to pay the full fees as laid out in the national schedule.

Nationally, what people pay for hospital services is defined by a patient fee schedule, that lists fees for procedures such as dialysis for patients with kidney failure, for which the state bills full paying patients about R2000 per session.

But health MECs can impose additional criteria and procedures concerning this, including fees for different groups of people. For instance, the Gauteng Hospitals Ordinance Amendment Act 4 of 1999 provides that the CEO of a hospital may require identification documents before admission to a hospital except where deferring treatment may have “dangerous or detrimental consequences” to the person seeking treatment.

The vagueness of the legislation’s wording leaves it open to a broad interpretation, meaning that this may be more widely used than it was intended to be. Hospitals need some proof of identification to see a patient, and they may also require proof of income. But the failure of staff to communicate what they need and how it can be provided can sometimes lead to patients being turned away when they are unable to offer a South African ID book or an asylum document or a refugee permit.

Patients that can’t produce these documents can, however, submit foreign passports or an affidavit.

A 2008 Gauteng health department memorandum also says that “no patient should be denied access to any health care service, including access to antiretrovirals, irrespective of whether they have a South African identification document or not”.

Finally, no one may be refused emergency medical treatment, including on the basis of ability to pay. This means that it doesn’t matter who you are or where you seek care, if it’s emergency treatment you need, you may be charged for it after it has been provided (based on the provisions above), but you can’t be required to pay for it before it is delivered.

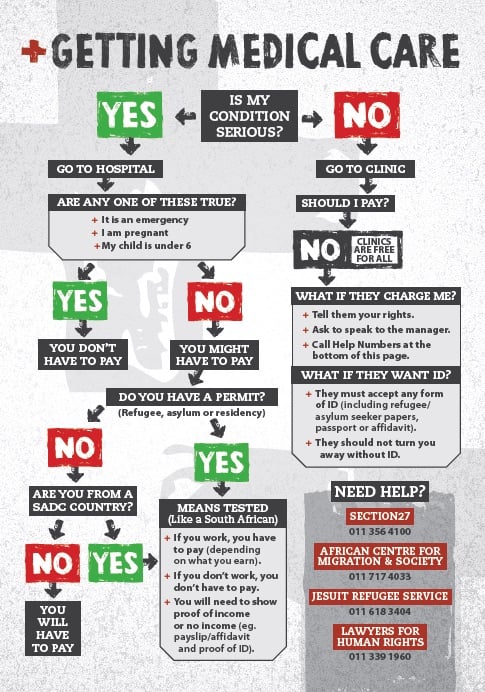

Confused? Check out this graphic

3. What do you need to know?

Basically, everyone regardless of their documentation is entitled to free primary healthcare, antenatal care, abortions as well as HIV and TB treatment. Pregnant, breastfeeding, under the age of six? Then your healthcare at clinics or hospitals should be free too.

If you’re not from here but are from a Sadc country, or you’re a refugee or asylum seeker, you should be treated just like South Africans at public hospitals and will be assessed to see how much you can afford to pay.

Everyone else? You’re looking at paying full price but just for hospital services.

Sasha Stevenson is the head of healthcare at Section27. Follow the organisation on Twitter @SECTION27news