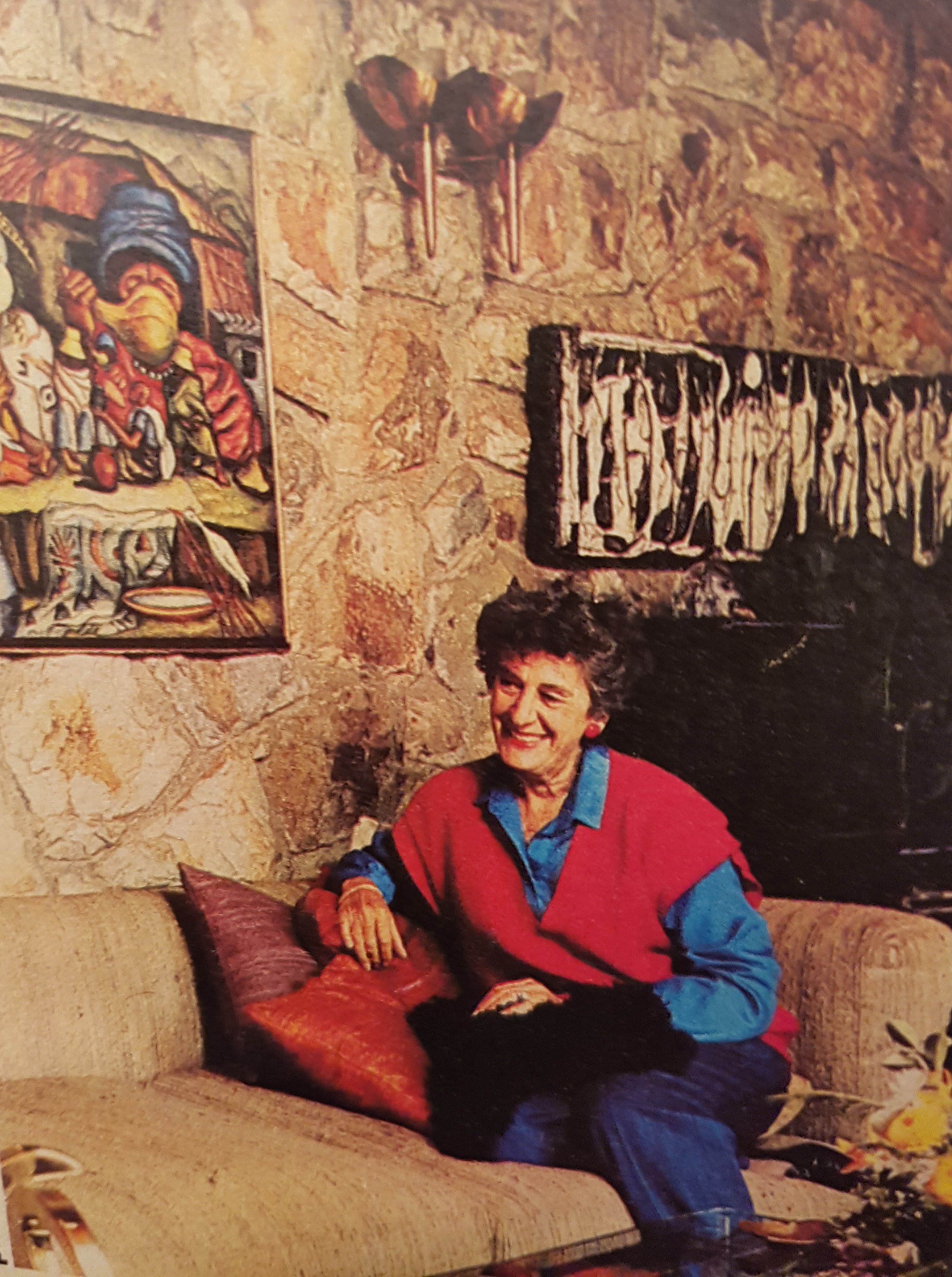

Esme Berman was a teacher, collector, researcher, author and is considered one of the most prolific historians of South African arts. Photo: Supplied

An unattributed poster in the Historical Papers Research Archive in the University of the Witwatersrand’s William Cullen Library reads: “Archives, whether spaces or records, are continually transforming and shifting in meaning. They are fundamentally political in nature and as such are mediated sites of power, ideology and memory. Ideological agendas and battles frame the contested archival terrain and notions of ownership, access, control, privilege, propaganda and fabrication underpin and shape archival policies and processes.”

An illustration of this statement is seen in the literary and audiovisual body of work that Esmé Berman created. She was a teacher, collector, researcher and author and is considered one of the most prolific early historians of South African arts.

After studying for a BA in Fine Art at Wits, the dawn of Berman’s career saw her reviewing art and artists for the SABC and magazine Newscheck. In the 1960s, she began using her evenings to teach culture, architecture and literature at the Hillbrow Study Centre.

Her teaching became the catalyst that fuelled her to write the first volume of her illustrated, biographical dictionary and encyclopedia, Art and Artists of South Africa (1970).

When the Dutch publisher AA Belkman turned down the request to compile her lectures into a book, Berman was encouraged to travel around South Africa to conduct original research on the country’s artists.

Artist and art historian Thembinkosi Goniwe sees the value in Berman’s work as a reference for those who are teaching and researching the arts during the period she covered because there were not many contenders at the time. But, considering its blind spots regarding the lack of black artists, it cannot be considered “an in-depth study of the times or of the artists”.

Berman recorded the likes of Jacobus Hendrik Pierneef, Alexis Preller, Maggie Laubser, Irma Stern, Cecil Skotnes, Armando Baldinelli, Larry Scully, Alice Goldin and Walter Battiss, as well as sculptors Edoardo and Claire Villa.

Esme Berman sits below Alexis Preller’s Basutho Allegory (1947) painting. Photo: Supplied

Using lengthy essays and an array of photographs, the book comprehensively captures white South African artists, their work, art practice and why they do what they do. Wits awarded her a LittD in recognition of her contributions in 2017.

But, as a entire reference, the first edition of Art and Artists of South Africa is far from complete because it makes no mention of the artists currently being exhibited at The Standard Bank Gallery’s A Black Aesthetic: A View of South African Artists (1970-1990). With a rigid criterion, Berman only solicited information from artists whose work had been exhibited, evaluated and promoted in public so the encyclopedia excluded the likes of Ernest Mancoba, George Pemba, Gerard Sekoto, John Koenakeefe Mohl, Dumile Feni and Gladys Mgudlandlu.

Considering the immeasurable inequalities and the legally enshrined racism of the times, Berman’s methodology was flawed because, no matter how significant a black artist’s work was, it was either cast to the side or excluded from public consumption.

The historian’s daughter, Kathy Berman, says: “My mother and I had such an antagonistic relationship. I was progressive and she had this colonial mentality. It was a white history. Her criteria for selection was very clear. The artists she would write about all had to have been publicly exhibited. That was her cut off.

“Was it a good criterion? I don’t think so. Did it cover hundreds? Yes.”

I first encountered Kathy Berman during a talk she hosted at the Strauss & Co offices last year. Titled Remembering Maggie Laubser, the talk was her personal recollection of encountering Laubser while accompanying her mother on a three-day interview in 1968.

“Forgive me for not seeing you at the talk, but there were no black faces there. It was desperately white,” she says moments after we settle on an L-shaped couch.

After her mother’s death in 2017, Kathy’s eclectic and colourful Morningside home has been transformed into a makeshift archive of living memory. There are heaps of boxes, stacks of books and her Macbook flashes the “endless Excel spreadsheets” of her mother’s inventory.

The possessions range include art encyclopedias dating back to mediaeval times, teaching handbooks, folders with photographs and handwritten manuscripts, interview recordings, letters to artists that were never sent, and newspaper clippings of everything she wrote.

When her mother returned to South Africa from Los Angeles in 2002, Kathy moved into the secluded complex where she currently resides.

For the duration of our interview, in between bottomless cappuccinos, Kathy and I take walks between the two homes filled with mounted art, research material and a library’s worth of arts and culture books.

“She was meticulous in how she managed things. There’s one folder which says ‘For when you’ve got nothing else better to do than laugh’. Every. Single. Thing is filed,” Kathy sighs, throwing her hands into the air and storming out of her mother’s deserted library.

Kathy’s initial plan was to sell her mother’s “stuff” to the Norval Foundation in the Western Cape and the Javett Arts Centre at the University of Pretoria. “I needed the money. But I realised that nobody wanted to buy them,” she shrugs. Although they hold immense research value, archives are not necessarily purchasable.

After talks with archivist Gabriele Mohale, Kathy saw it fit to donate what her mother left behind to the William Cullen Library’s Historical Papers Research Archive.

“They have got Ronnie Kasrils’ archives, they have got Nadine Gordimer, Phillip Tobias … I remember one night being in a bus going to an art exhibition with Nadine, Phillip and Esmé and I joked that it was three egos on a bus. So I looked at this and thought, ‘Why would I want her stuff to be anywhere else?’ ”

Beneath the theatrics of Kathy’s spirited and critical commentary about her mother is a deep reverence for the artistic insight and confidence that she afforded her. It is for this reason that she has gone to such lengths to preserve her intellectual memory.

“From the age of five, I sat at my mother’s feet and we went on trips around the country where she conducted original research. Other kids had playgrounds, I played on sculptures. My best friend was Alexis Preller. I was a lucky precocious little shit,” she admits.

A young Kathy Berman (right) sits with her mother and brothers. Photo: Supplied.

Like her mother, Kathy is an arts writer, broadcaster and a Wits alumnus. “We lived in such extreme danger. I reported on the arts because that’s how we could get the story out locally,” says Berman, when asked about the similarity between her and her mother’s professional trajectory.

Berman’s outlook was shaped by existing in a world broader than her mother’s. When her father’s business required him to supply entrepreneurs such as Richard Maponya with catering items, she would accompany him to the township.

At Wits, her “world was turned upside down. From a comfortable middle-class existence, surrounded by innovation, design and abstract African art, I now lapped up abstract political theory … Every night was spent in clubs in Hillbrow — and later Yeoville — talking politics and revolution. Neil Aggett died in detention. Eddie Webster was assassinated. And soon all that I had been taught to treasure was, to my mind, a symptom of white excess and middle-class privilege,” she wrote in her mother’s unpublished biography, Public Encounter: The Life & Work of Esmé Berman.

A view of the Berman family home with a Edoardo Villa sculptor. Photo: Supplied

In an attempt to counter this excess privilege, her byline appeared in The Weekly Mail and Vrye Weekblad during the 1980s. She then moved to television in 1994, when her team covered the first democratic elections for the SABC.

This was followed by her producing television shows, The Works and Artworks, which was referred to as a show “that changed people’s perceptions of the way culture could be presented to the South African public”, by the Mail & Guardian in a 1999 piece titled “But is it good?”

Kathy Berman interviews a muralist in Alexander. Photo: Supplied

As such, Kathy’s response to her mother’s orbit has been to build a canon of work that fills the gaps her mother left open. “She captured the art world until the Sixties. I captured the art world from the Eighties to the Nineties. I’m okay with our archives being an intergenerational conversation between Esmé and me. I didn’t realise how much of that history lives with me. I don’t realise how much isn’t obvious. We need to put the history out there so we can make an informed decision on how to construct our current and future realities.”

Rather than a complete achievement, the memory of Esmé Berman’s work, as one curator said, raises issues about how institutional frameworks enable canonisers and the extent to which access can unconditionally translate into competence and knowledge. It begs one to ask who gets canonised and why?