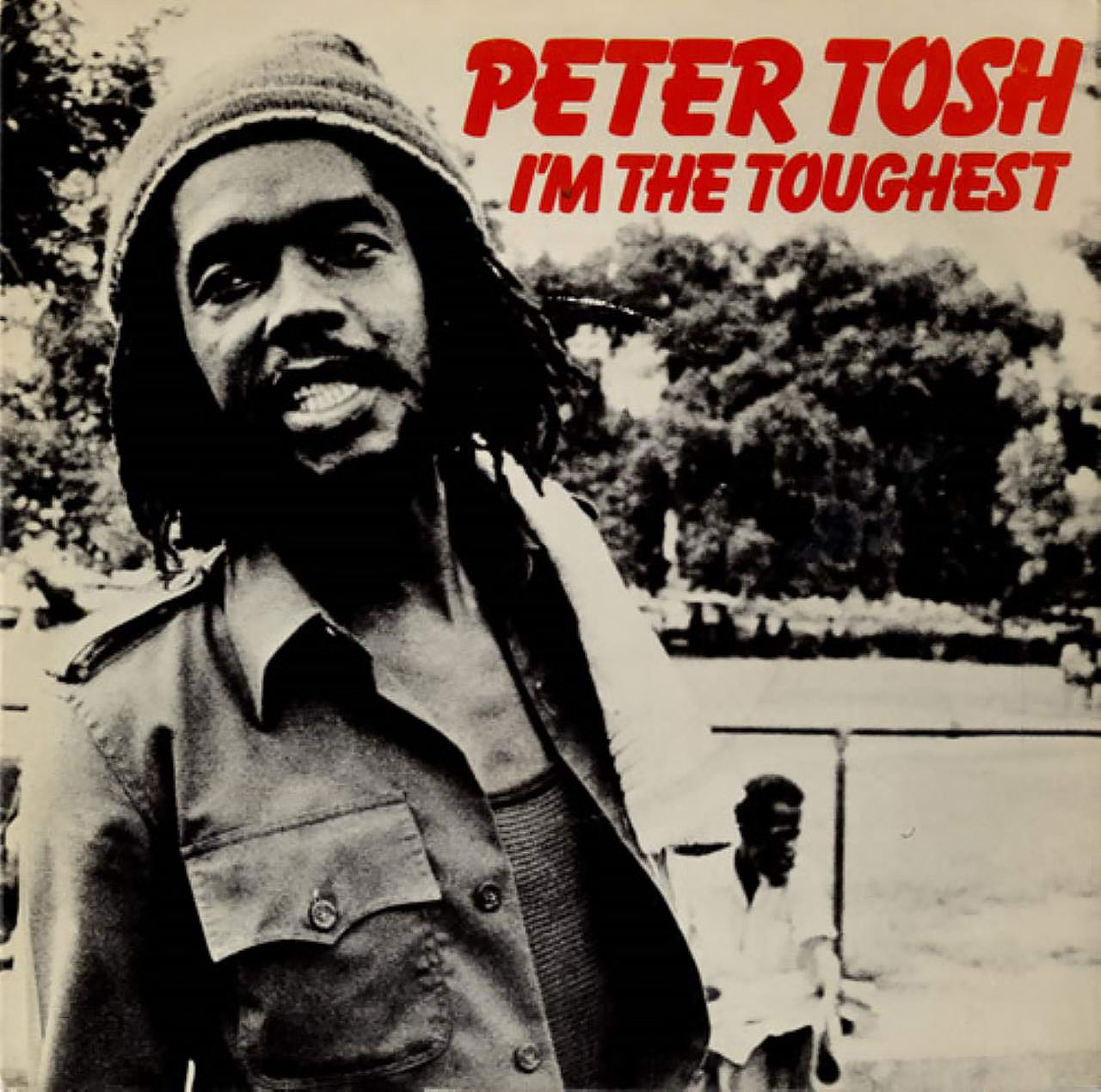

Commitment: Kwanele Sosibo was seven when he was lifted up by the sound of Peter Toshs 'The Toughest' on the radio. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

My first experience of music happened between the intertwining contexts of Radio Zulu, Bantu education and Radio Freedom.

Because the classes in my primary school in eNanda could not accommodate all the pupils, on some days of the week, lessons would be held under a tree. On these days, school would take place a little later than normal, meaning that at least once a week I could be entertained by the high-octane antics of Radio Zulu’s Jimmy the Bongo Man before leaving the house.

An image burnt into my memory is of my seven-year-old self lacing up my black Idlers in my mother’s bedroom — khaki shorts and shirt already on — while he introduced Peter Tosh’s I’m The Toughest through the radio.

In the late 1970s, Tosh had got himself into a marriage of convenience with The Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards and Mick Jagger, releasing a trio of albums under their label, where specific songs were often given a crossover sheen. The Toughest, for example, was remade into a gospel-like number with a clap-along backbeat not out of place with reggae.

Peter Tosh: The Toughest

Lyrically, its rudeboy boast was reframed even more intentionally into a sport of spiritual one-upmanship. At the time, though, alone in my mother’s room, I didn’t know any of that. All my seven-year-old self felt was a levitational moment, in which my little body was seemingly lifted by the harmonies of the background singers as they counterbalanced Tosh’s lower registers in the bridge.

In that sliver between Sly Dunbar’s trotting drums and Tosh’s baritone, it suddenly dawned on me that the air was not as calm as it seemed. A membrane had been pierced, and the gap would keep widening — one beat at a time.

My school was in walking distance of a shack settlement pre-emptively called eNamibia (this was the mid-1980s). One day, a mutual friend introduced me to a group of older youths who lived there. They were already in their mid-teens, despite being in higher primary school. On one visit to their house (a two-roomed shack overlooking a valley dotted with shacks and mud houses), they made it a point to play Brook Benton’s blues lament Oh Lord, Why Lord on their uncle’s record player.

As a parting gift, they hooked me up with a bunch of tapes — probably recorded from Radio Freedom broadcasts — but not before mouthing off some of the words and explaining their meaning. I remember repeatedly playing a choral song with the lyrics: “Ayangqikaza, ayesaba amagwala, athi kungcono sibuyele emumva. Qiniselani nina maqhawe sekuseduze apho siyakhona [The cowards are advising us to turn back/ Push forth heroes, the destination is near].”

As if to balance out the heaviness, on other visits to my newfound friends’ home they would whip out Clarence Carter’s Live in Johannesburg record and blast it across the lounge; the sound filled the small gravel courtyard used for washing. A cultural boycott-flouting raunch fest recorded in 1982, the album must have been something of a guilty pleasure for my mates, given their political orientation.

But in between the libidinous funk of Lookin’ For A Fox and the Motown-esque bop of Take It Of f, was the story of Patches, a vivid blues tale about the coming of age of a sharecropper’s son.

My new friends (I called them cousins, because we shared a surname) became my ticket to several worlds. There was the physical terrain of eNamibia — a sloping settlement of self-built dwellings that was muddy in the rainy months. There was their politicised context, in which December trips to the beach started with toyi-toyi sessions in the Putco bus. Then there was their trove of music, which gave me an internal life, instinctively connecting me to black worlds I was yet to fully know.

By the time I was sent to a Zululand boarding school, music was providing comfort to disorientation. Beyond the words and the rhythm, there was a certain texture of sound that my spirit would be drawn to, a feeling I was then unable to articulate.

The pied piper this time — or our Radio Raheem — was a lanky kid named Louis, who lugged his gumba gumba to our weekend boarding house walks to the nearby dam. You had to walk close to him to catch the sounds.

In the chaos of our 100-man strong walks, with a cane-wielding matron as our chaperone, I remember having a moment with Tracy Chapman’s Mountains O’ Things, a sparse song whose import I would understand perhaps a decade later.

While he was at boarding school, Tracy Chapman’s voice in Mountains O’ Things transported him, even though he did not understand the lyrics.

At the time, Chapman’s voice, which had isolated foolhardy greed as its theme, was enough to carry me home.

Oh they tell me

There’s still time to save my soul

They tell me

Renounce all

Renounce all those material things you gained by

Exploiting other human beings

In those moments, 150km away from home, Louis was saving my soul. The man with the boombox was always the man with the escape plan — from the indoctrination by the nuns, from the summer Christian camps and the racism underpinning all those contexts.

From my mother I acquired my own boombox. I admired its row of equalisers, tried out different variations to see how each felt in my chest. During the school holidays, my mother’s constant refrain would be, “Ngicela wehlise lento ethi gqu gqu gqu,” meaning “turn down the bass”.

The last time I had a truly transformative experience through music was in 2010, at the hands of Detroit house producer Theo Parrish, whose exploits I had hitherto read about as opposed to experiencing. His set at the Albert Hall during a Pan African Space Station festival event was a sermon on DJ-ing as sonic rewiring. Parrish did not mix songs so much as he rearranged them through feats of physics mediated through his mixing desk.

By this time, the music had lost its words and bass had long taken me into its inner sanctum. Paths to the self were being discovered through webs of intricate rhythms, and electrified — often programmed — approximations of spiritual jazz.

For a person with two left feet, the process often felt like involuntary exorcism as opposed to a co-ordinated flow of release. But with the boombox (the turntable) as the altar and the record sleeve as the script, it doesn’t take much these days for lift-off.

Thinking back to 1986 or thereabouts, I understood individual English words, but not enough to make sense of complete lyrics. What was being transmuted through songs like The Toughest, Patches and Mountains O’ Things, were not so much verbal ideas but ways of expressing a singular outlook, and therefore compassion.

Because of his handling of the song, I swear I understood The Toughest as a declaration of martyrdom as opposed to an injunction to brute force (it is probably both). Although I knew nothing about the Deep South, I could hear the anguish of Patches’s father through Carter’s yelps.

Although I understood little of Chapman’s songwriting, I could hear her protagonist drown in the grave of a vanity she had dug for herself — one of worldly goods acquired directly from the skin of the average working man.

What I understand now about what was being communicated to me then, was that music, and indeed life itself, is nothing if not lived with a commitment to the moment.

What I’ve come to learn, for example, from the elemental playing of someone like Philip Tabane, is the interconnectedness of things: “my cousins” being political emissaries hiding out in the relative safety of eNamibia, my mother enabling me to be all I could be by feeding my addiction to music, the excitable antics of Jimmy the Bongo Man connecting with souls he would never actually meet.