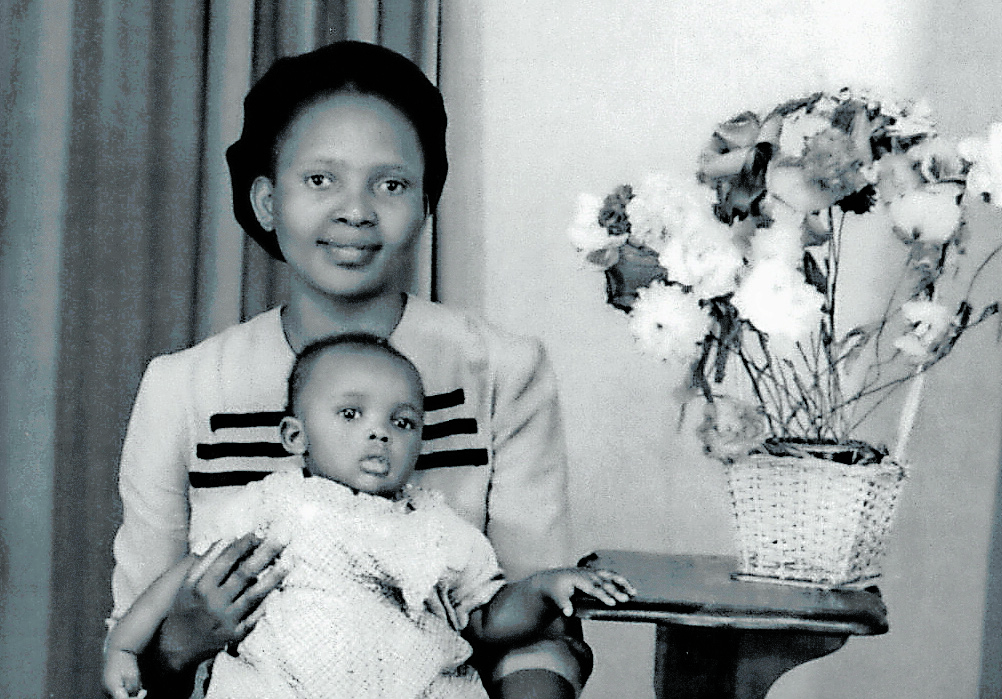

Friends of Mama Sobukwe celebrate with her upon her release from detention

Zondeni Veronica Sobukwe’s life is an amazing testament to the ways in which care was central to the struggle against apartheid. From her days in the nursing profession, to the ways she cared for Robert Sobukwe and all incarcerated political prisoners, to the maternal care she gave to her children and community in Kimberley, Soweto and Graaf-Reniet – Sobukwe is affectionately and rightly referred to as the Mother of Azania.

Sobukwe was born on July 27 1927 in Hlobane in Kwa-Zulu Natal. Her parents Kate and Henry Stini Mathe had four daughters, and Veronica was the second-oldest of the Mathe siblings. Henry Mathe worked on a mine in Hlobane, and her mother, Kate, was a teacher at the local school, but the white racist government unfairly dismissed her from her position. In that time, her father had come into acquiring an old farm, which was to be their home until the government evicted them.

“It is was here, at her home, that Mama Sobukwe first experienced the institution of white supremacy, the apartheid state and police, as the racist settler regime ordered for the eviction of her family from their home under the pretext of a safety law. Her family was evicted from their homestead and they were allocated to what was then referred to as ‘Skomplaas’, a small little room, divided with strings and cloths, in which the whole family was cramped,” wrote Thando Sipuye, Sobukwe family friend and programme director at the Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Trust.

Even though the family was evicted, Henry Mathe managed to keep the family’s cattle, and the duty of taking care of the livestock fell on the four girls. Through the harsh and unjust living conditions, all the children learnt self-sufficiency and to take on tasks diligently and responsibly. The traits of resilience and hard work found expression in Sobukwe throughout her life. In mission school, she was a stellar pupil and by the time she went to Victoria Hospital as a trainee nurse, she was self-assured, and knew injustice when she saw it. Her time at Victoria Hospital was an exercise in her natural leadership skills, as when a labour dispute came up between nurses and hospital management, she led a strike that brought the hospital to a standstill.

It was at this time that she and Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe met. They met each other through their activism, as Robert, who was SRC president of Fort Hare, came to support the young nurses at Victoria Hospital. They were both taken aback by the political fervency and activism of the other. When she was asked how she felt when she met Mangaliso she replied: “I loved him at first sight”.

During their courtship period, they both travelled around South Africa in their chosen professions – nursing and teaching respectively. From Victoria Hospital, Veronica went to work in Durban (at the Springfield, and McCord Hospitals) and then in Ladysmith. Robert was teaching in Standerton at the time he got the call from University of Witwatersrand to teach in their African Languages department. Veronica and Robert relocated to Johannesburg together. They soon got married, in 1954 in Jabavu, and she received the marital name Nosango.

For a time, the Sobukwes lived in Mofolo and engaged in the realities of making a family. The couple moved into her mother’s house at 1526 B White City, Jabavu, Soweto.

“After nine months they were allocated their own municipal house at 68 Mofolo in Soweto. Shortly before they moved into their new house their first child, a daughter named Miliswa, was born. Then shortly before they moved into the new house, their first son Dinilesizwe, and finally twin boys, Dalindyebo and Dedanizizwe, were born. Mama Sobukwe resumed work in between having the children, doing general district nursing in Soweto,” wrote Sipuye.

March 21 1960 is a day of significance in the Sobukwes’ lives, as well as the country’s political trajectory and resistance politics. The Sharpeville Massacre occurred when apartheid police brutally shot and killed 69 black people, and leaving scores more injured. Robert, heading up the newly formed Pan-Africanist Congress’s (PAC) Positive Action Campaign against pass laws, was arrested and sentenced to three years’ hard labour in Pretoria Central Prison.

From that day onwards, the Sobukwe family structures that existed were thrown into disarray — all members of the family were harassed by security police to varying extents and, even when Robert’s sentence was over, the apartheid government still incarcerated him under the Sobukwe Clause, which stated that he could be held in prison for any amount of time. This was a testament to the brutality of the regime, as well as how much the racist government feared the Sobukwes’ strong presence in the anti-apartheid struggle.

“Since my future is still so uncertain, I thought I should take this opportunity to tell you just how much your courage and love have meant to me during all these years of my imprisonment. Human nature is a queer thing, Darling. You have been everything I could have wished my wife to be. And I mean that, Little Woman. And the children, too, will agree with me,” wrote Robert in a letter to Veronica in 1963, from prison.

When speaking about this period of imprisonment, Veronica submitted the following to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC):

“In 1963, my husband was to be released on the 30th of May, but he was not released. The Government refused. He was one of the people who built up an organisation. They then decided that they will pass a Sobukwe Clause so that they can keep him. It was on the third of March. On that day I was knitting the jerseys for the children. He also said that I must cook him dinner, because he was coming back home. When I went to visit him I was told that he was transferred to Robben Island under the Sobukwe Clause,” she testified.

Once on Robben Island, Robert’s health deteriorated exponentially. As a health practioner herself, Veronica understood, through the information received in letters from Robert, that he was being deliberately malnourished and not treated properly for his health issues. She wrote letters to the racist government, appealing for Robert’s release and all political prisoners’ release, for improved healthcare, and generally agitated the apartheid government. But as much as she wrote to the government, none of her concerns were listened to.

One of the concerns she raised was about broken glass being put into Robert’s food — a fact he mentioned in one of his letters to her. In the same TRC hearing, Veronica attested to this.

“In February 1966 they transferred him to Karl Bremer. They did not tell me. I heard about this when he came back from Karl Bremer. He stayed there. He was admitted under a false name. They sent him to Karl Bremer under a false name. I do not know anything about that. He then came back, he was taken to Robben Island. They did not consult me about this. When I went to visit him the following year his condition deteriorated. I then wrote another letter. I was writing twice a year asking for his release. I wanted him to be treated. In 1965 or 1966 he complained that his food was served with broken glasses,” she said.

Throughout the period of Robert’s unjust incarceration, Veronica worked as a nurse and midwife in Soweto. In 1966, a month before Veronica’s 40th birthday, Robert wrote the following in a letter to her:

“We have come a long way together, and we have watched each other grow and mature. And we have watched the children God has blessed us with grow. We occupied a building in Mofolo and turned it into a home. You denied yourself luxuries and worked uncomplainingly to achieve this. The children and I thank you and bless you. You’ve been a widow now for over six years. But you have been a father and a mother both to our children and they have grown up like other children lacking nothing that you could give them.”

Her resilience and care for all those around her was palpable to everyone — most of all her husband in prison, her children and political supporters. In the period of Robert’s incarceration, from 1960 until 1969, Veronica continually and regularly wrote letters to Parliamentarians such as Helen Suzman, pleading to help Robert, and she provided invaluable support to the PAC and its members.

In 1969, Robert was released in poor health, and sent to stay in Kimberley under a banning order, with many further restrictions on his movement. From his release until his untimely passing in 1978, the Sobukwes stayed in a municipal house in Galeshewe in Kimberley. In that time, Veronica worked at West End hospital, which specialised in tuberculosis treatment. Speaking to Kwanele Sosibo, Constitutional Court Judge Yvonne Mokgoro, who knew the Sobukwes during this time, said the following about Veronica: “She played a supportive role at home. Some of the children were there and she’d participate in the conversations when people came home, just like in an ordinary couple. The conversations were political but not in a partisan political manner. They were highly charged conversations about the nature of the system of apartheid.”

As much as Veronica and Robert cared for and supported each other, and had the community to rely on, the government kept on denying Robert specialist treatment for his lung cancer or obfuscating his prognosis, as different doctors had different opinions on what caused his ill health. In 1978, he passed away.A few days after the funeral she and her family were kicked out of their house in Galeshewe. Veronica tried to settle in eSwatini but could not buy land, as she was a foreigner. She then tried to settle in Alice, but eventually she settled in Graaf-Reinet, Robert’s birthplace.

Unfortunately, Robert’s death was not the last in Veronica’s personal, family life. Her youngest sister, Florence Vemba Ribeiro and her husband Fabian Riberio, were assassinated by South African Civil Cooperation Bureau military/death squad on December 1 1986 in the courtyard of their home.

“The Ribeiros were political activists who used their medical and nursing profession to help ordinary people in the black community pro-bono during the darkest days of apartheid. When Mangaliso Sobukwe was incarcerated on Robben Island under the draconian Sobukwe Clause, the Ribeiros often accompanied Mama Sobukwe to visit him a number of times,” wrote Sipuye.

The bonds between Florence and Veronica were strong – both were recognised as leaders by their peers, and both were women activists deeply embedded in community work. Beyond that, they were sisters. The loss of the couple was devastating, as the Ribeiros supported Veronica through many trying times.

But, through these hardships, Veronica remained an active member of the community in Graaf-Reinet and formed relationships with local nurses at public hospitals in the area. She also saw the plight of the elderly in Graaf-Reinet and tried to alleviate their pains by facilitating ways in which the elderly could access medication easily and be taken to hospital when it was needed.

In 2018 Veronica was nominated by young activists of the Blackhouse Kollective in Soweto to receive the highest honour in the land in recognition of her contributions to the liberation struggle. In April 2018 the South African Government conferred the Order of Luthuli in Silver on Mama Sobukwe for her tenacious fight for freedom and her steadfast support of incarcerated freedom fighters.

On August 15 2018 Mama Sobukwe died peacefully in her family home in Graaf-Reinet. She is survived by her three children, Miliswa, Dinilesizwe and Dedanizizwe, as well as her great-grandchildren. Veronica was known for her honesty, kindness, caring personality and dry sense of humour by those who loved her.

“Mama Sobukwe was a steady and resilient revolutionary grounded in the ethos of Afrikanism and Afrikanist discourse. She became an activist at an early age since her days at Victoria Hospital where she led the nurse’s strike, and later became one of the founding members of the PAC of Azania. She epitomised the collective experiences of many Afrikan women throughout the continent, whose roles and contributions in the liberation struggle remain unacknowledged, written out of popular historical narratives, biographical memory and national consciousness,” wrote Sipuye.

Dinilesizwe ‘Dini’ Sobukwe was quoted as saying the following to The Citizen, with regards to his mother’s passing. “We were blessed with a strong and resilient mother. She went through severe persecution by the apartheid regime but never lost her positive spirit. We were persecuted for carrying the name ‘Sobukwe’ and at times we were forced to split as a family for our own safety, but she would always gather us together,” he said.

Gordon Zide, Vaal University of Technology vice-chancellor and principal, explains Veronica Sobukwe’s role and deep significance to the PAC, her family and community. “When Robert Sobukwe launched the PAC, he said ‘Here is a tree, let us sit in the shade of this tree.’ We, as VUT, add to that and say ‘Here is Mama Sobukwe. She is a tree of liberation, a tree of peace, a tree of compassion, a tree of integrity. Here is a tree that can nourish and develop us,’” said Zide.

She was a hands-on and grassroots based activist – and her marriage to Robert Sobukwe was one of love, and where they met as equals. She was a humble person who endured extreme adversity and inhuman treatment by the apartheid regime, with an even deeper resolve and commitment to humanity and care.