Tastes of travel: Delicious dishes, inspired by faraway lands. Photos: Supplied

Growing up in KwaZulu-Natal, I had very little exposure to Cape Malay cuisine. I’d heard of bobotie and koeksisters, but that’s where my knowledge ended.

I’d been told that Cape Malay curries were milder and sweeter than our fiery Durban curries, so in my mind Cape Malay food was full of sultanas and raisins and apricots, and would be far too sweet for my Durban palate. I had no idea that, although Cape Malay cooking does include sweetness, the sugar is offset by sour, tangy and salty flavours to create balanced dishes.

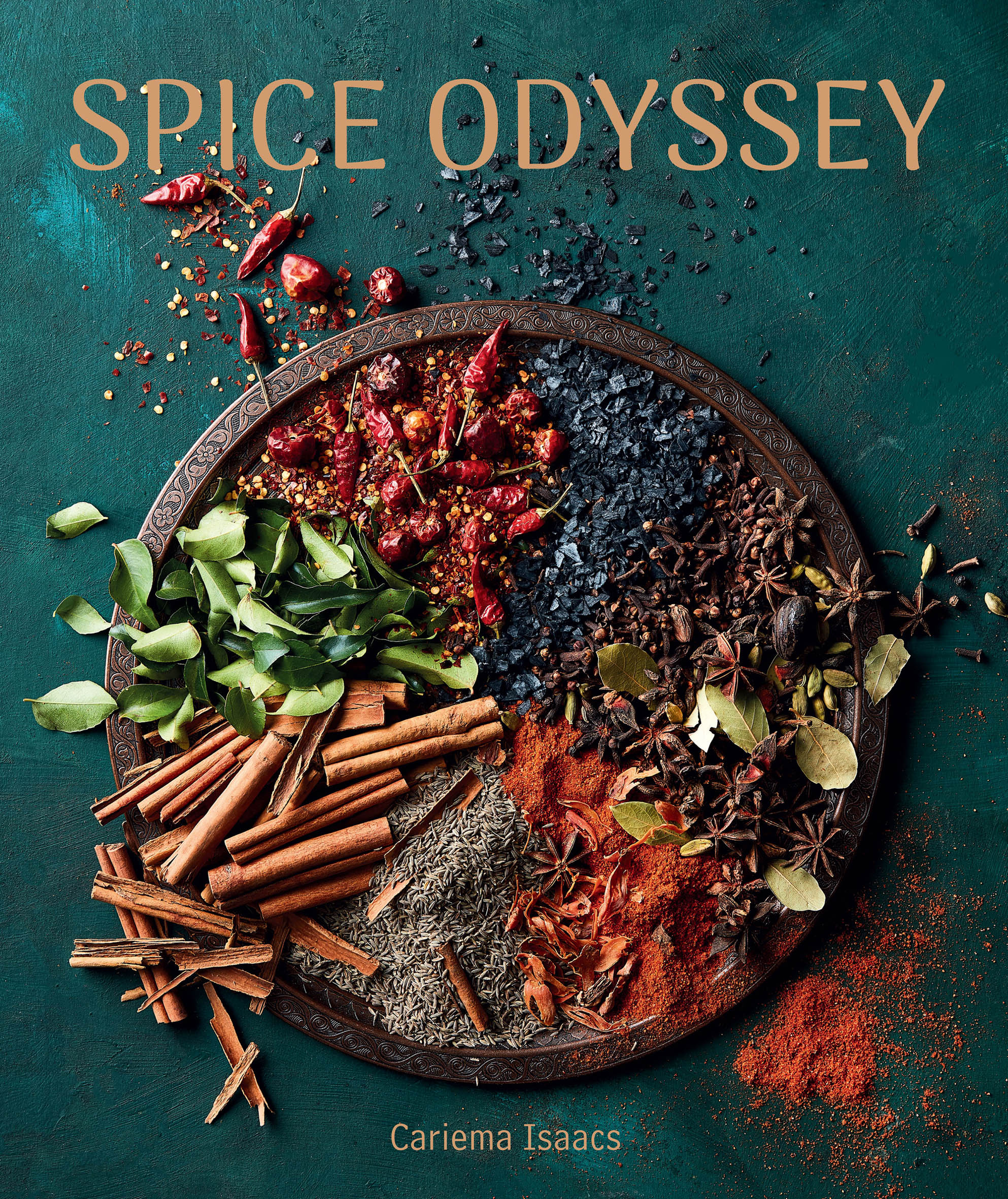

My introduction to Cape Malay cuisine comes from Cariema Isaacs’s new cookbook, Spice Odyssey. Her recipe for Cape Malay dried red chilli blatjang (chutney) is a harmony of contrasting flavours.

First step: sweat the onions. I was comfortable with this. Just like a curry, onions are a critical component; they create the base for all your flavours. Next, you add brown vinegar, tamarind, salt and smooth apricot jam.

I stood over the pot and took in the aroma. I was hit by an intense wave of vinegar heat, like pure acid hitting my nostrils, and thought, “How can this ever become a chutney?”

As the flavours started to mellow and blend together, I realised all the ingredients complement each other: saltiness, sour vinegar, sweet jam, and tangy tamarind.

Tamarind trees, native to tropical regions, produce bean-like pods surrounded by a fibrous pulp. The pulp of the young fruit is green and sour. As it ripens, it becomes paste-like and develops a sweet-sour flavour, thus nicknamed “the date of India”.

After reducing the liquid, and a quick blitz with a hand blender, the mixture resembled chutney as I’m used to it. The last step, adding and gently simmering a heap of dried chilli flakes, provided heat: the final flavour component to balance the chutney.

Isaacs explains that blatjang is a historical preserve in Cape Malay culinary heritage: “Like the traditional Cape Malay denningvleis, this is one of the older recipes found in Cape Malay cuisine. The name blatjang comes from one of the constituents of the Javanese sambal, blachang. There are also two types of blatjang: one is the fruity kind which, ultimately, gave birth to Mrs Ball’s Chutney, and then there is the spicy, tangy kind. The latter is one I know intimately because it is an essential accompaniment to fried fish in the Cape Malay Quarter.”

Preserves became an important characteristic of Cape Malay cooking because it was a way to preserve fresh produce.

Author of Spice Odyssey, Cariema Isaacs says the book was inspired by the delicacy and complexity of spices. (Supplied)

In 1652, the Dutch East India Company needed labourers for the newly established port and re-supply point at the Cape of Good Hope. They began transporting Javanese slaves from their colonies in Southeast Asia. These slaves brought recipes and indigenous spices from their home countries, but when those spices were not available, ingredients were substituted, and the modified recipes became Cape Malay cuisine.

“Both my grandmothers and great-grandmothers made konfyt, blatjangs and atchars. They could take seasonal fruits and vegetables and turn them into the most delicious and indulgent preserves, both savoury and sweet,” writes Isaacs.

Isaacs’s first book, My Cape Malay Kitchen, was all about Cape Malay cuisine and the food she cooked for her father. Recipes such as sweet-spicy pumpkin fritters and cauliflower bredie evoke the unique flavours and heritage of Bo-Kaap. “The first book was an ode to my father, my swansong to him. Everything about my heritage, my culture, the way I was raised, and how food was always a part of that,” says Isaacs.

She grew up in Bo-Kaap, the Cape Malay Quarter in Cape Town. She says the saying, “It takes a village to raise a child”, exemplifies the Bo-Kaap community. Doors were always open and food was always shared.

“Growing up, we ate a lot of bredies and curries. You can’t have one without the other,” says Isaacs. “In a week, you would have at least one chicken curry and one mutton curry — mutton on a Sunday because it would accompany the Sunday roast chicken. On Eid, it would be something more regal like a crayfish curry or a prawn curry.”

Isaacs was the youngest of three children, and spent her days in her grandmother’s kitchen.

“Other kids grew up playing with building blocks and dolls; I played with my grandmother’s spice jars. I had a little oven, and all of my toys were either tea sets or cutlery — anything to do with the kitchen. I sat on the tile floor in the kitchen, playing with her spice jars. I would close my eyes to guess which spices they were. I knew turmeric from the very beginning because of its bright yellow — it reminded me of the sun. I would say to her, this is borrie.”

At the age of four, Isaacs not only understood what each spice was used for, she understood the importance of balance: “Even when I’m using a variety of spices, the quantities are never excessive because, from a young age, I was told how to balance spices.”

Isaacs was inspired by the delicacy and complexity of spices, which led to her second cookbook, Spice Odyssey.

Isaacs has lived in Dubai with her two sons and husband Turhaan for the past nine years, exposing her to a variety of international cuisines through travel, and her expat community in Dubai.

“You could have a proper English breakfast in the morning and then have Lebanese or Italian for lunch. It just depends whose house you’re going to,” she says.

In Dubai, Indian food is still celebrated and Middle Eastern desserts, such as baklava, are a staple. Bengali fish curry, Sri Lankan beetroot curry and Lebanese batata harra show the spectrum of international recipes featured in Spice Odyssey. They represent the fusion of modern and traditional cuisines that Isaacs loves to cook in her own home.

“The second book is a reflection of who I am and what I love. It’s how the book got its name — it’s about my own journey and discovery along the way.”

Isaacs explains that each chapter not only describes the dishes, it defines her relationship with her husband. Her front page inscription reads: “Turhaan, I finally understand now that the words that gave rise to the chapters in this book are the very things that bind us together.”

Chapter names such as Cherish, Essence and Warmth represent the couple’s love, loyalty and the life they have built together.

Through all Isaacs’s travel and spice exploration, her favourite meal remains a Cape Malay chicken curry. “A luscious and fragrant curry is the epitome of warmth and comfort to me and one that transports me to the countries where these curry spices hail from,” she says.

Chillies are not all equal

Cumin rice as prepared in Spice Odyssey. (Supplied)

Dried Chilli Flakes

Bright red with a medium to hot intensity. Chilli flakes used in Italian dishes are usually crushed dried cayenne chillies. Kashmiri chillies are commonly dried and crushed for use in Indian cuisine.

Cayenne Pepper

A spicy red pepper related to hot peppers such as jalapeños. Great for adding a bit of heat to pasta dishes or tomato pizza sauce.

Chilli Powder

Bright red and fiery. Used to provide heat in curries. The potency of the chilli powder depends on the type of chilli that has been dried and ground.

Paprika

Commonly made from dried, ground bell peppers. There are two varieties of paprika commonly used in cooking: spicy paprika and smoked paprika. Smoked paprika is often used for Tex-Mex and Spanish cuisine.

Peri Peri

Bird’s eye chilli was originally cultivated in southeastern Africa but spread by the Portuguese to their Indian territories. It can be used in the same way as paprika, but has more heat so should be used sparingly.