Shocking science: The campus of Stellenbosch University, where the problematic research article originated. (Courtesy of Stellenbosch University)

RACISM

In 1937, the zoology department at Stellenbosch University enlisted 133 men for a study. At the time, the field of physical anthropology was focused on documenting “racial types” and this study helped to scientifically construct and confirm the category “coloured” to distinguish these men from “white Afrikaners”.

Handri Walters wrote her PhD thesis on race, science and politics at Stellenbosch in 2018. She unearthed the data sheets from the 1937 study, which measured skin colour, eye colour, hair texture and more than 80 other measurements of the head and body to determine racial type.

In March 2019, researchers from the department of sports science at Stellenbosch published an article titled Age- and Education-Related Effects on Cognitive Functioning in Coloured South African Women. It concluded: “Coloured women in South Africa have increased risk for low cognitive functioning as they present with low education levels and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours.”

Eighty-two years after the 1937 study, Stellenbosch is still uncritically using the term “coloured” as a frame for research. The use of this colonial and apartheid category in a scientific study resulted in an outcry from academics and social media users alike.

“For scientists and research, it is really difficult,” said Elmarie Terblanche, one of the authors of the Stellenbosch article. Speaking in an interview on Cape Talk radio, Terblanche said: “We have to look at different racial groups, we have to specify. All population groups have different problems and we have to characterise that.”

A statement was put out by the Cape Flats Women’s Movement in response: “We are the demographic of your study. Life on the Cape Flats is brutal and the challenges we face are endless. We don’t think you can even begin to imagine what kind of mental ability this takes. How do you think our children look at us now that a famous university has declared their mothers to be idiots?”

A team of scholars decided to use their voices to speak out against bad science. The team — including Barbara Boswell and Shanel Johannes from the University of Cape Town, Zimitri Erasmus from Wits, Kopano Ratele from Unisa and Shaheed Mahomed of South African History Online — drafted a letter to the editors who published the article.

“We ask that you retract it [the article] because of its racist ideological underpinnings, flawed methodology and its reproduction of harmful stereotypes of ‘Coloured’ women.” The letter became part of a campaign that gained more than 10000 signatures.

Many South African scholars have documented the history of racism and sexism in science in this country. Saul Dubow in his 1995 book, Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa, Yvette Abrahams in her articles including The great long national insult (1997), and Ciraj Rassool and Martin Legassick in their book Skeletons in the Cupboard (published in 2000 and updated in 2015) are among the important voices that have contributed to the understanding of this history.

The juxtaposition of the two Stellenbosch studies reminded me of my own shock when I began research for my book Darwin’s Hunch: Science, Race and the Search for Human Origins, published in 2016. Racism and sexism in science have deep roots and go back centuries.

In the mid-1700s, Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, developed the modern system for classifying all living things and published Systema Naturae. He categorised humans as Homo sapiens. Yet, Linnaeus classified the Khoisan and “Hottentot” people of southern Africa in a separate category: Homo monstrosus that included “monstrous or abnormal” people. With this one act of naming and classifying, he sent a dehumanising, painful ripple-effect across the centuries.

In the early 1900s, it was not unusual for scientists in Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States to believe humans could be categorised as distinct racial types and each type could be classified by its physical characteristics. Many scientists embraced the ideas of a racial hierarchy and white supremacy.

Raymond Dart, the head of the department of anatomy at Wits, was inspired by universities in the US and the UK to establish a human skeleton collection in an effort to clarify racial types. Dart also led the first expedition of researchers from Wits to the Kalahari Desert in 1936 because he was interested in the “Bushman anatomy”.

Thanks to a footnote in an important chapter of Deep hiStories: Gender and Colonialism in South Africa (2000) by Rassool and Patricia Hayes, I learntof a young woman from the Kalahari named /Keri-/Keri. Dart, according to Rassool and Hayes, took interest in her “in life and death” because he thought she represented a “pure bushman”. So, he took her body measurements and face mask while she was alive, and her body cast and skeleton after she died.

In the same year as the Wits expedition to the Kalahari,/Keri-/Keri was brought by Dart to Johannesburg for further research. She was put on display at the Empire Exhibition celebrating Johannesburg’s 50th anniversary. My research into the Dart archives revealed that a doctor in 1939 alerted Dart that /Keri/Keri had pneumonia and was at Outdshoorn Hospital. Anticipating her death, Dart immediately made arrangements for her body to be transported to Johannesburg.

Several days later, /Keri-/Keri died. In many ways, /Keri-/Keri’s story is reminiscent of Sarah Baartman’s, who had been examined by the French anatomist George Cuvier more than a century earlier. Dart saw /Keri-/Keri’s body and her skeleton as a specimen to be studied. For close to 60 years, her body cast remained on display at Wits and her skeleton remained on a shelf in the Raymond Dart collection of human skeletons.

In the wake of World War II and the Holocaust, Unesco drafted a statement on race in 1950, which began: “Scientists have reached general agreement in recognising that mankind is one; that all men belong to the same species Homo sapiens.”

In the same year, the apartheid government implemented the Population Registration Act of 1950, which defined a “coloured person” as someone “who is not a white person or a native”.

Scientists in South Africa continued to work with the concept of “race typology” well into the 1960s. Phillip Tobias, the successor to Dart as head of the department of anatomy at Wits, continued to embrace the existence of racial types, which largely coincided with apartheid’s racial classifications. Tobias built the face mask and skeleton collections at Wits into the 1980s.

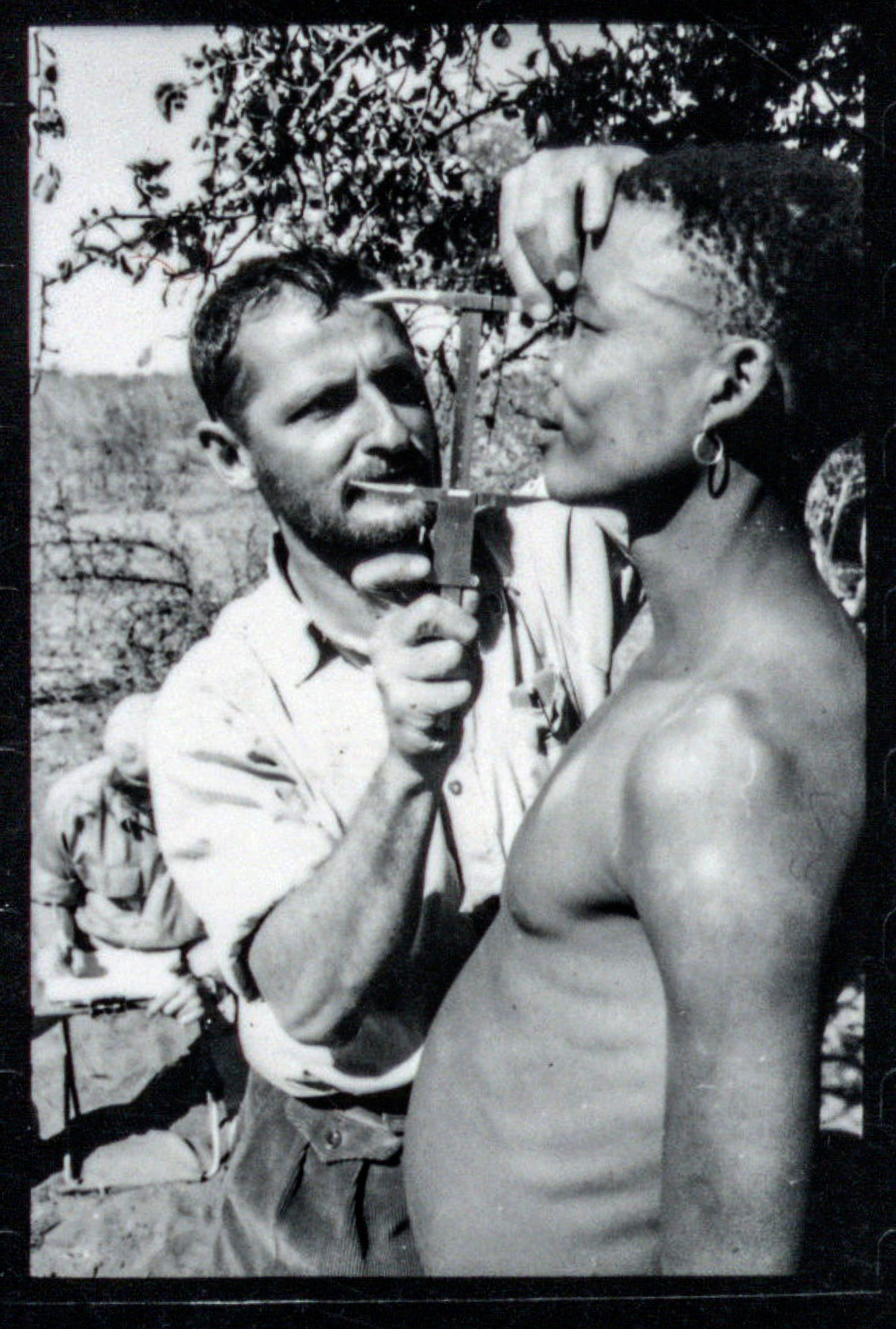

Wits University Professor Phillip Tobias measuring an unnamed person during an expedition to the Kalahari in the early 1950s. (University of the Witwatersrand)

In March 2019, just weeks before the Stellenbosch study was published, the American Association of Physical Anthropology put out a new statement on race.

“Racial categories do not provide an accurate picture of human biological variation”, it said, adding “the Western concept of race must be understood as a classification system that emerged from, and in support of, European colonialism, oppression, and discrimination”, and “no group of people is, or ever has been, biologically homogeneous or ‘pure’.”

In the wake of the campaign to retract the journal article, the Psychological Society of South Africa put out an open critique of the study: “The authors have unjustifiably and exploitatively used the apartheid-inspired understanding of race.”

Initially, the university’s deputy vice-chancellor for research, Professor Eugene Cloete, said the findings of the study were those of the authors alone, but in a later statement, he “apologised unconditionally for the pain and anguish which resulted from this article”. The statement made no mention of the faulty scientific assumptions and methodology. Subsequently, the university announced it would conduct a “thorough investigation into all aspects of this study”.

On May 2, the editors and publisher of Ageing, Neuropsychology and Cognition, the UK journal that published the Stellenbosch study, retracted the article, noting: “While this article was peer-reviewed and accepted according to the Journal’s policy, it has subsequently been determined that serious flaws exist in the methodology and reporting of the original study.”

However, the retraction did not critique the framing of the study specifically for its focus on “coloured women,” nor did it acknowledge the perpetuation of racist stereotypes.

The campaign team pointed out this was not only an issue for the four white women researchers. The problem goes much deeper; it is systemic. There is a new generation of academics that did not see the problem.

Everyone who spoke out against the study sounded an important alarm. The lesson is not only for Stellenbosch, but for every academic and research institution in South Africa and around the world to promote sound science.

Each university and journal must reflect on its assumptions in biology, medicine, natural sciences, anthropology and the social sciences. This episode points to the need for greater diversity in these fields, as well as on ethics committees, among peer reviewersand on editorial boards.

See “Caster treated like Saartjie Baartman, Page 41.

Christa Kuljian holds a BA in the history of science from Harvard University. She is the author of Darwin’s Hunch: Science, Race and the Search for Human Origins (Jacana, 2016), a research associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research and is working on a new book about the history of sexism in science