The theme for World Health Day is 'healthy beginnings, hopeful futures' and aims to encourage governments to take actions to reduce mothers' deaths during pregnancy and childbirth.

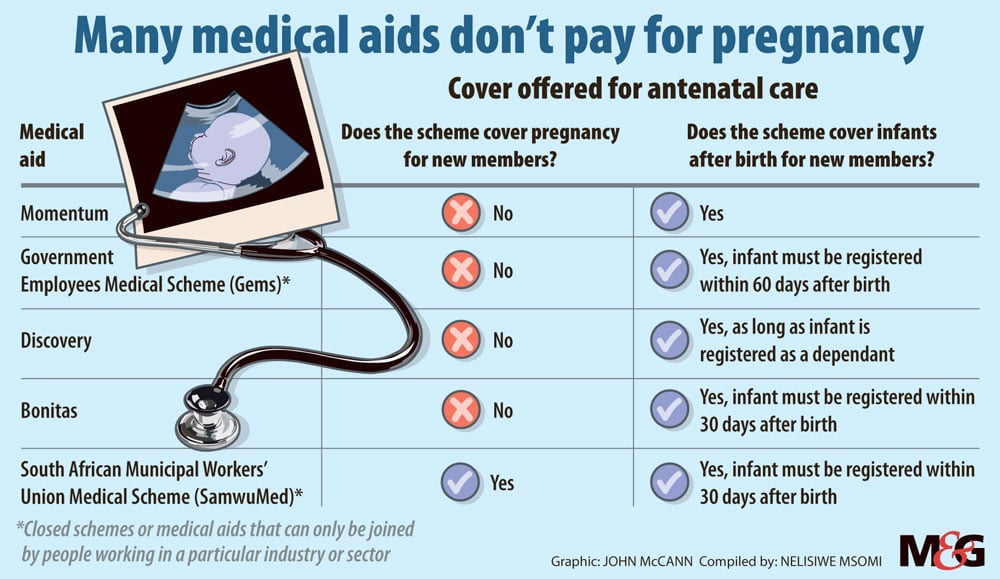

If you fell pregnant today and sought out a medical aid, here’s who would and wouldn’t cover you. Here’s why.

By law, medical schemes must cover a set of 270 conditions called prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs), regardless of what kind of plan a member has. The Medical Schemes Act of 1998 introduced PMBs to help safeguard consumers from losing medical cover in the event of serious illness.

But today, despite the government’s commitment to reducing maternal mortality, standard antenatal care still isn’t a PMB. However “antenatal and obstetric care necessitating hospitalisation, including delivery” is a PMB, according to the full list of PMBs stated on the Council for Medical Schemes website.

Long-time health activist Fatima Hassan recently told Bhekisisa why:

“The 1998 Act established South Africa’s first Council for Medical Schemes (CMS). [It] marked the end of an era in which member premiums were determined partially or entirely by how much patients with health conditions were likely to claim.

“But not everyone was happy about the shift… It took massive legal battles and public campaigning against business interests to get the industry to align with the goal of social solidarity — the idea that healthier members should cross-subsidise those with greater health needs.

“In return, the industry was permitted to implement late joiner penalties and general waiting periods (three months). Longer waiting periods for pre-existing conditions that do not appear on the PMBs were also allowed and, incredulously, included pregnancy.”

During general three-month waiting periods, new members pay monthly premiums but are not entitled to any benefits, in some instances not even for PMBs.

Seem unfair? Discovery Health CEO Jonathan Broomberg explains that waiting periods are crucial to managing what’s known as “anti-selection” — a phenomenon in which healthy people only join medical aids when they need them, like when they fall sick.

And medical aids need healthy members, who claim less, to subsidise the cost of other members — like those who are elderly or live with chronic conditions — who might claim more, he explains.

“If anti-selection were not managed, it would lead to medical aid claims exceeding contributions and, in turn, increase premiums dramatically and essentially make medical schemes unaffordable”, he told Bhekisisa.

“The total cost of antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care can range from R60 000 to several millions of rand…,” Broomberg says. “If medical schemes had to pay out these costs for members who joined only at the time of pregnancy — and who could then leave after the pregnancy — the premiums paid by these members would never be enough to cover the costs incurred by the scheme.”

But Hassan says it’s time that civil society challenges these concessions.

“It’s time to challenge these concessions because until the National Health Insurance is fully rolled out, many working women who can afford to, will rely on basic or entry-level medical scheme plans,” she argues. “They do so to save time in queues, to travel shorter distances to a clinical facility near their work or home, or to get tested and screened in a clean facility at fixed times that make sense for their work commitments and family obligations.”

She says: “The time has come for civil society and progressive, committed health professionals and medical schemes — with government support — to change the law and the rules.”