Above: Green sea turtle with a plastic bag, which can be confused with jellyfish. The bag was removed by the photographer before the turtle had a chance to eat it. (Photo: Troy Myne/WWF)

“Globally, we are increasingly concerned about microplastic and nanoplastic pollution in the ocean, because if a particle of this size is ingested by fish, it might be small enough to transfer across the walls of the digestive system and into the organism, possibly accumulating in organs such as the brain, liver and kidneys,” said Dr Andy Booth, senior research scientist in the environmental technology department at one of Europe’s largest independent research institutes, Sintef Ocean, in Norway.

Speaking at the Sanocean conference at Nelson Mandela University in March 2019, he explained that microplastic particles are less than 5mm in size and nanoplastic particles are less than 100 nanometres — they are so small you wouldn’t be able to see them. “Estimates are that what we see is only about 10% of the total marine plastic pollution. What this means is that about 90% of plastic litter is already on the sea floor.”

Research is being conducted by the Fortran project (factors influencing the formation, fate and transport of microplastic in marine coastal ecosystems). It’s a partnership between Sintef Ocean, Stellenbosch University, the University of the Western Cape and Wildoceans — a programme of the Wildtrust in KwaZulu-Natal.

“Very importantly, different plastics and polymers contain a broad range of chemicals, some of which are added specifically to make the polymers more resistant to degradation. Some chemicals are very toxic, and this is a big unknown at the moment. What we need to identify, as part of coming up with solutions for plastic pollution, is which are the benign and which are the toxic materials.

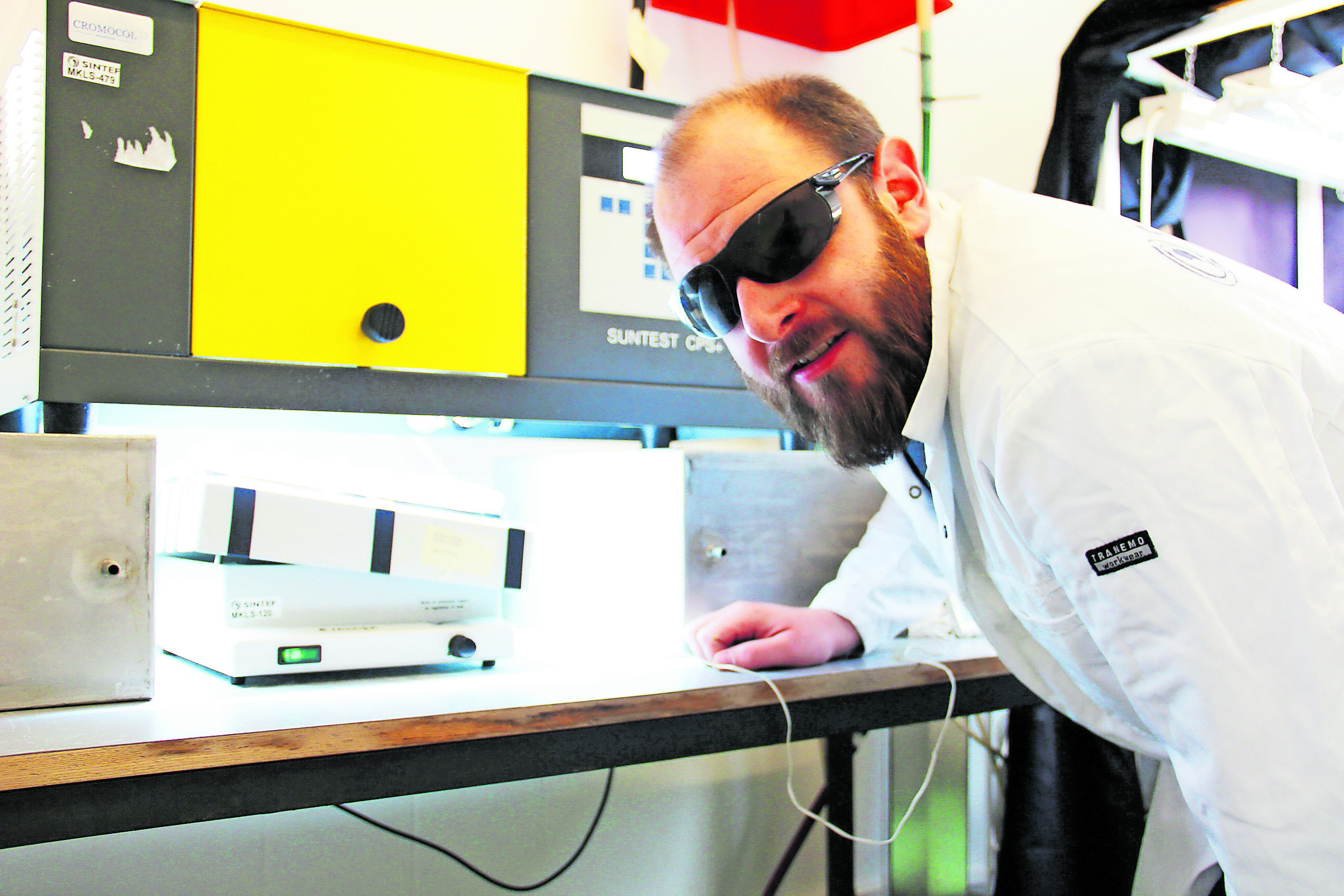

Dr Andy Booth simulating UV degradation of microplastics in freshwater and seawater

Dr Andy Booth simulating UV degradation of microplastics in freshwater and seawater

Toxic tyres

“We know, for example, that vehicle tyres are not benign. Not only are they one of the highest volume emitters of microplastic particles, which are continuously released when the tyre comes into contact with the road surface, but they have some of the most toxic chemical additives in their composition,” said Booth.

He said that the average car tyre loses 1.5kg in its lifetime in the form of micro- and nanoplastic tyre wear particles that are released directly into the environment. Therefore, every car with four wheels releases 6kg of micro- and nanoplastic into the environment — into the land, freshwater sources and oceans. Scale up to the number of cars in the world and this may be one the main sources of micro- and nanoplastic particles polluting the ocean.

To determine their toxicity, microplastic tyre particles were added to fresh and seawater and the Fortran research team analysed the metals and chemicals that came out. “We found that they are really toxic,” says Booth. “We are now looking at the transport route and toxicity effect of tyre wear particles on test organisms in the ocean, including microalgae, zooplankton and small sediment crustaceans.

“Obviously you can’t ban car tyres, but what can be done is to assist, guide and regulate tyre manufacturers and other producers of plastic to better manage their plastic footprint, to develop products with reduced plastic particle pollution and to replace the toxic chemicals in plastics with non-toxic counterparts.

“What we can also do is to look at the points of origin of high flows of macro and microplastic into the environment. A good example is wastewater treatment plants — these are ideal points for targeted management,” concluded Booth.

For more information:

https://www.sintef.no/en/

http://wildtrust.co.za/wildoceans/