Radical statement: Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu (above), who formed Juluka after performing together as a duo called Johnny and Sipho. (Media24)

This piece by Richard Pithouse was first published in the Mail & Guardian in October 2000 to mark the 21st anniversary of Universal Men, the celebrated debut album by Juluka. Today we republish it in honour of Johnny Clegg, a musician whose crossing has elicited an extraordinary moment of public grief and remembrance. Universal Men, first released in October 1979, was the beginning of a remarkable career in music, and the generation of poetic meaning, that profoundly shaped many people’s understanding of South Africa, both locally and around the world

In the mid 1970s Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu started playing together as a duo under the name of Johnny and Sipho. Their infectious melodies and gentle presence didn’t disguise the fact that this union between an illiterate gardener from rural Zululand and a Jo’burg academic was as radical a musical statement as it was possible to make at the height of apartheid repression.

But Johnny and Sipho were a lot more than just Verwoerd’s worst nightmare. From the earliest days their music was infused with a remarkably perceptive engagement with their time and place that made it as timeless and universal as anything by Marley or Dylan.

Sipho Gumede, who was laying down bass grooves for the out-there jazz band Spirits Rejoice at the time, remembers: “I saw Johnny and Sipho playing as a duo at the Market Cafe and I was excited by what I saw. It was the first time I’d seen a white guy playing African music and the music was very strong. We got talking and they invited us to join the recording project.”

So in 1979 Johnny and Sipho went into the studio with the country’s best musicians — people of the calibre of Gumede; Mervyn Africa, who went on to play with Jazz Africa in London; Colin Pratley from the legendary Freedom’s Children, who now runs a home for babies with HIV in Durban; and Robbie Jansen, who, of course, remains the inimitable Robbie Jansen.

Their producer, Hilton Rosenthal, had a simple plan: “To avoid commercial pressures and to give the musicians a mandate to experiment and be spontaneous. I thought we’d just put them in a room and see what came out.” The gamble paid off, spectacularly. Johnny Clegg remembers: “The most incredible aspect of the recording process was that the jazz musicians from Spirits Rejoice managed to sound completely different to their normal sound. The whole project was, musically, completely new. No one had done this before — we were flying a kite and hoping to be struck by lightning.”

Juluka poses in London in 1983. (Fin Costello/ Getty Images)

Twenty-one years on, Gumede enthuses that “Universal Men still sounds fresh. It’s one of those albums that will be there for life. It was an innocent album. We went into the studio with the aim of making great music. No one was thinking about how many units we would sell. We just thought about the music.”

Rosenthal speaks for many when he says: “There’ve been other great moments — like Asimbonanga and Scatterlings —but Universal Men is my favourite album. I have a hard time thinking about Universal Men without the hair on my neck standing up.”

The band believed, firmly, that they had produced something important, but everyone in the industry told Rosenthal that it was “too black for whites and too white for blacks”. No radio station under the jurisdiction of the apartheid state would play the album, so Rosenthal took it to Capital Radio in the Transkei, which played the single, Africa, to an enthusiastic but tiny listenership, and to Radio Swazi where Mesh Mapetla burst into tears when he heard Africa.

The album hit the streets in late October 1979. The sleeve carried a picture of two men — one white and the other black. They were dressed in paisley waistcoats, beads and car-tyre sandals. But they weren’t hippies. Mchunu looked into the camera with all the resoluteness of a revolutionary. Clegg gazed into the distance with a questioning intensity.

The name of the band appeared as an engraving on a gold bar. Its shimmering glitz clashed pointedly with the more organic colours of the sky, the rocks, the men and their clothes. Juluka means sweat in Zulu and the message couldn’t have been clearer: Johannesburg’s wealth and glamour is built not just on gold but also on the sweat of the men, the migrant labourers, who mined that gold.

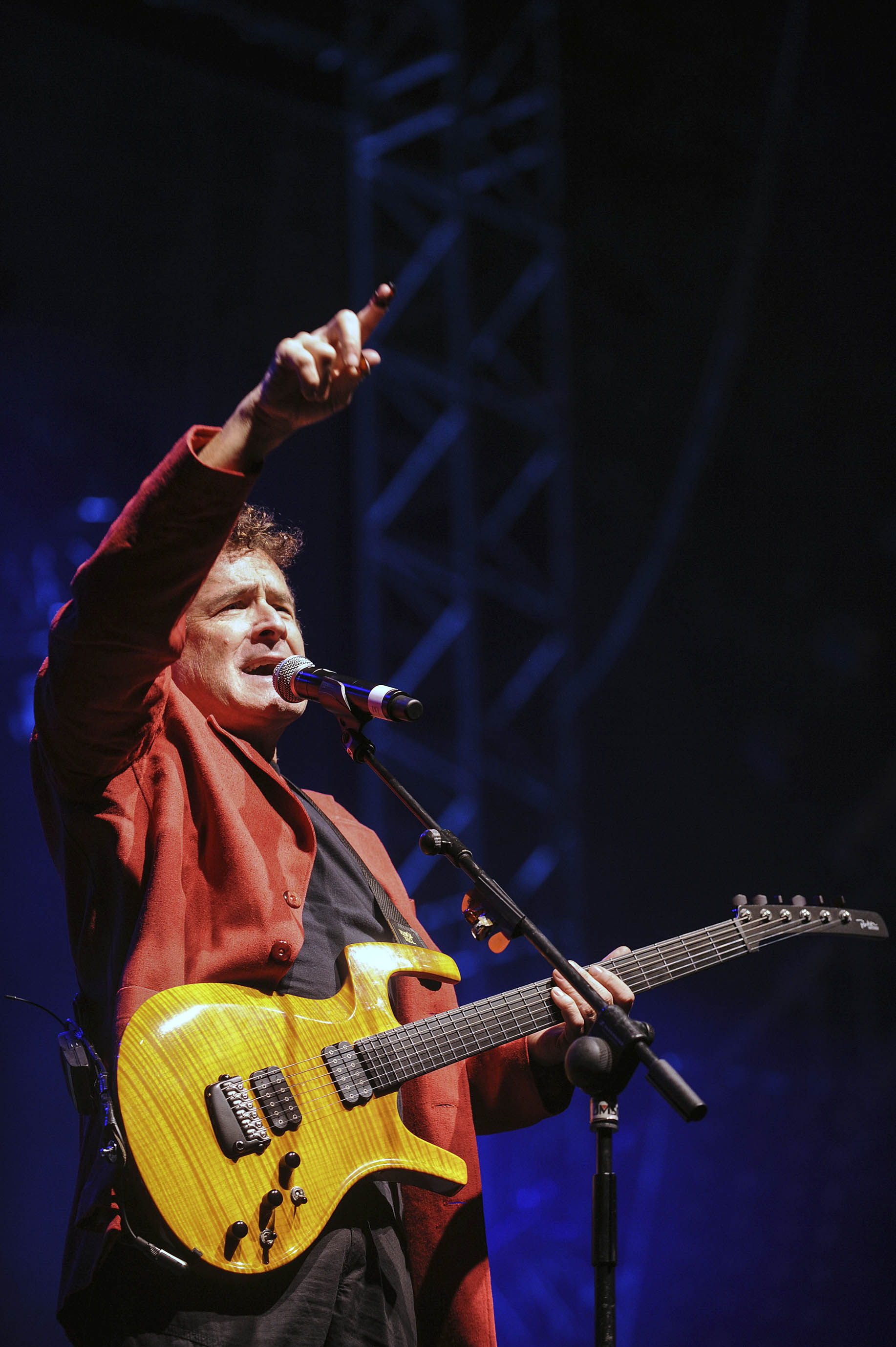

Universal man: Johnny Clegg performs in 2010 in Toulouse, southern France, at the Rio Loco world music festival. The songs on his first album with Juluka addressed migrant worker issues. (Remy Gabalda/AFP)

But Universal Men was a world away from the abstract sterility of Marxist dogma. On the contrary, it was as if the words of an African Pablo Neruda had been set to the most sublime music — a very human response to an inhuman society.

Clegg explains: “Universal Men is about bridging two worlds. Going and coming. While the worker is en route, on a bus or a train, he is given the time to look over the distances, geographic and otherwise, in his life. Migrant labourers in Africa, Europe, everywhere are like universal joints. They are this incredible human resource who are just sucked up by the capitalist system and used anywhere. The system makes no concessions and so the workers have to create a whole new universe of meaning.”

The album is a largely acoustic mixture of Anglophone and rural Zulu folk. Clegg’s lyrics have an extraordinary rhythm, depth and emotive power. Clegg explains: “There was so much hardness in the migrant life and yet I experienced incredibly human moments with my buddies. They lived such a rich and full life with a highly developed sense of humour and understanding of human nature. For me, there was something magical and mystical in this bleak life and I felt that I needed another language to capture it and to humanise the suffering.”

Clegg was reading John Berger’s A Seventh Man, a book about migrant labour in Europe, while the album was being composed. Berger’s book influenced the album in terms of both content and style. The lyrics are often a little otherworldly, or perhaps old-fashioned, and tend to focus on archetypal aspects of themes like home, loss, family, desire and work, and the weight of time, distance and history. The result is that the lives described are, as in the lives witnessed in Berger’s book, removed from the detail and messiness of the now and given an eternal or universal dimension.

The album opens with Sky People. The title refers directly to the amaZulu — the people of the sky (iZulu). One man’s story rolls, like a wave on the ocean, across the larger story of his people — their past and their hopes for the future. He asks: “Where did the time, time, time go?/ My old eyes can hardly see the green fields leaving me behind/ I worked the earth and turned the blade with a strong heart and steady hand/ Seasons wheeled across the sky/ I turned around and found that I was old/ Trembling heart body cold/ Wind and rain take their toll.”

The album was recorded just months before Zimbabwe won its independence and Clegg remembers: “There was a huge fight in the studio. I wanted to use the line ‘The drums of Zimbabwe speak/ They roll across the great divide’, but everyone was convinced that would lead to the album being banned, so we eventually changed it to ‘The drums of Zambezi speak’.”

But the next lines remained: “Smiling spear with teeth of white/ Give me strength to face the Night/ Ancient Song Bless My Life/ See me through to see the morning light.”

Many of the themes introduced on Sky People were developed further on later albums and this is also true of the second track, Universal Men. Clegg explains that the title track is the pivot on which the whole album turns.

It pays respect to the workers with whose sweat prosperity was built: “From their hands leap the buildings/ From their shoulders bridges fall/ And they stand astride the mountains and they pull out all the gold/ The songs of their fathers raise strange cities to the sky.”

The chorus, with its nod to Neruda, is a meditation on separation and homecoming. “I have undone this distance so many times before/ That it seems as if this life of mine is trapped between two shores/ As the little ones grow older on the station platform/ I shall undo this distance just once more/ My brother and my sisters have been scattered in the wind/ Dressed in cheap horizons which have never quite fitted/ And for centuries they’ve travelled on that pale phantom ship/ Sailing for that shore which has no other shore.”

For a while the vision seems bleak: “The rivers of their homelands murmur in their dreams/ They’re shackled to that distance till heaven lets them in.”

But then Clegg finds a way to affirm the resilience of hope. “Well they could not read and they could not write and they could not spell their names/ But they took this world in both hands and they changed it all the same/ And from whence they came and where they went nobody knows or cares/ Cast adrift between two worlds they could still be heard to sing.”

The third song, Thula ’Mtanami, has all the evocative power of an archetypal lullaby. It is beautifully sung by Mchunu and was included on the album because, according to Clegg, “Sipho knew that his wife would be singing it to their child back home.” One can’t help but wonder if migrant workers don’t also sing lullabies to parts of themselves.

Deliwe, the fourth track, was overlooked for years, but it was taken to a large new audience when it featured on the carefully put together Putumayo compilation, A Johnny Clegg and Juluka Collection. It has recently been worked into the Juluka set list and many now rate it as their favourite Juluka song.

It’s the only song on the album that doesn’t deal directly with the migrant labourer experience, but it is part of the broader theme of movement and separation in that it is about a person, Deliwe, deciding whether to leave South Africa. It warns that not all waters wash us on the inside and that, in a foreign land, Deliwe will be haunted by the melodies of Africa and, eventually, judged by the north winds (a metaphor for the winds of change sweeping down from the north). The song’s simple prayer has haunted more than a few expatriate South Africans and persuaded just as many to return home and live in hope: “Oh, Bless this water/ Bless this land/ Give us food to eat/ Let our herds span the hills/ Let them graze in peace/ If soldiers march across our fields give them eyes to see/ The children singing in the sand/ Songs in the north wind.”

The next song, Unkosibomvu (The Red King), begins with a sound that is somewhere between Malombo and AmaMpondo, and develops a slightly ominous tone — as though there’s danger beneath the surface. Clegg explains that it deals with the martial psyche that is able to generate enormous power but also has a dark side. The Red King refers to “a romantic iconography of a mythological bloody king whose ability to force his will on others is admired”.

Africa, which was Capital Radio’s first-ever No 1, remains a live favourite. Its sing-along chorus, means, in translation, “In Africa the innocent are always weeping.” Clegg describes it as a cryptic song that refers to the strong rural belief that good is limited while evil is pervasive, and so the good suffer while the bad prosper.

Uthando Luphelile, the seventh track, has a much harder edge than anything else on the album and, musically, it anticipates the Juluka-inspired African rock movement of the late 1980s led by bands like Via Afrika and éVoid. The lyrics have a tight, edgy, urban feel.

Clegg describes it as “a very weird song” and explains: “I was trying to look at the problem of prostitution at the migrant hostels — at the power of the slick city girls and to make the point that bourgeois men are also trapped by the same illusions about fantasy women.”

The song warns that once you’ve “seen her in the disco club busting out all over”, she: “… infiltrates your desire and makes you open wide/ She walks down the convolutions of your cerebellum/ And tickles the right hemisphere with an electric tongue/ You will buzz round her like a fly/ … But you will never get to hold that woman/ ’Cause she’s a phantom in your mind.”

Old Eyes is a moving song about homecoming. Clegg explains that, for the migrant labourer, “Homecoming is everything — you’re carrying presents and it’s the moment when you reveal yourself to your community as a successful person. You become a source of abundance; it’s an elevated and life-giving moment in the migrant universe. There is redemption. All the degradation and alienation which you’ve endured is redeemed and transformed into a hugely meaningful event when you arrive home.”

But in this song, the longed-for redemption is out of reach — shattered between the anvil and hammer of apartheid. The returning worker finds that he is the “only one to witness my homecoming” and reflects that: “When I left that mountain land so gold and green/ I was a sturdy 16 years/ The work was hard and the wage was low/ And the seasons passed me by one by one/ And I dreamed, Maria, you would wait for my return/ We’d build a home upon the rock beneath the smiling sun.”

He finds an old man he remembers from his youth who tells him that: “Son, I’ll be old until I die now/ And then I will join our people in the sky/ I am not the one to ask why our people have been scattered in the wind/ You’ve got old eyes — amehlo madala — you’ve seen much too much for one so young.”

The album ends with Inkunzi Ayihlabi Ngokumisa, which is a reworking of an ancient war song sung by Mchunu and adapted to the evocative sounds of Clegg’s mouthbow. The title refers to a traditional idiomatic expression that means, in translation, “A bull doesn’t stab by means of the way in which its horns have grown.”

It’s a beautiful piece of music and the gentle, meditative interpretation speaks of a softness — an openness to new ways of being. It was an inspired way to end the album.

Universal Men sold only 4 000 copies when it was first released. But two years later, radio stations on both sides of apartheid’s colour line gave in to a groundswell of popular demand and allowed Impi, from the second Juluka album, African Litany, to become a massive hit. As Rosenthal remembers, rather ruefully, “Universal Men was suddenly the great first album.” It soon went gold and has never stopped selling.

Impi: Johnny Clegg in a Zulu outfit at his wedding to Jennifer Bartlett in 1989. (Trevor Samson/AFP)

Part of the magic of Universal Men is that it was the start of a brilliant career for Juluka. Each of their increasingly militant six studio albums, with their stories of hope and struggle, is a coherent and powerful statement. There’s not a single song that doesn’t remain a captivating listening experience. It’s a remarkable achievement.

With the exception of the incandescent Heat, Dust and Dreams, none of the Savuka albums were as artistically potent as the Juluka ones. The lyrics were always well crafted, intelligent and important, and there were fragments of transcendent insight. But the records tended to sound like collections of songs rather than thematically focused artistic projects, and their use of the pop sounds of the time give them a slightly ephemeral feel.

The Savuka period did produce one magnificent song though —Asimbonanga: a soaring tribute to the then imprisoned Nelson Mandela. It was on the first-ever Savuka release, a four-track EP, and soon took its place with Mannenberg and Weeping as one of the great entries in our national songbook. But the poppier Savuka material did win major international success that, in turn, won the band, their vision of transcendence and their back catalogue major respect in white South Africa. Such are the sad ironies of colonial culture.

Juluka re-formed in the late 1990s and released the forgettable Ya Vuka Inkunzi in 1997 that was later rereleased as Crocodile Love. They are set to release another album shortly and are still, through their live performances, a vital force in South African culture.

Clegg and Mchunu are still passionate people and may well make great music again. Perhaps, as with Bruce Springsteen’s The Ghost of Tom Joad, they may reinvent themselves by returning to their acoustic roots and record another album with the gentle potency of Universal Men.

The world has changed a lot in the past 21 years, but lives are still shattered by the machinations of inhuman forces. A new vision of resilience and hope from Juluka would be entirely welcome.

• Sipho Mchunu was not available to be interviewed as he was on holiday at the time of writing (in 2000)

• Richard Pithouse is now an associate professor at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, the co-ordinator of the Johannesburg office of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research and the editor of New Frame