Pedal to the metal: Kumba Iron Ore's Sishen mine produces lumpy ore, which fetches a premium. (Madelene Cronjé/M&G)

Power shortages, slow growth, policy uncertainty, a tense labour environment. These are the problems typically cited for holding back a mining company’s performance. But, judging by the interim results reported by the likes of Anglo American Platinum and Kumba Iron Ore this week, these usual suspects have not been enough to dampen their fortunes.

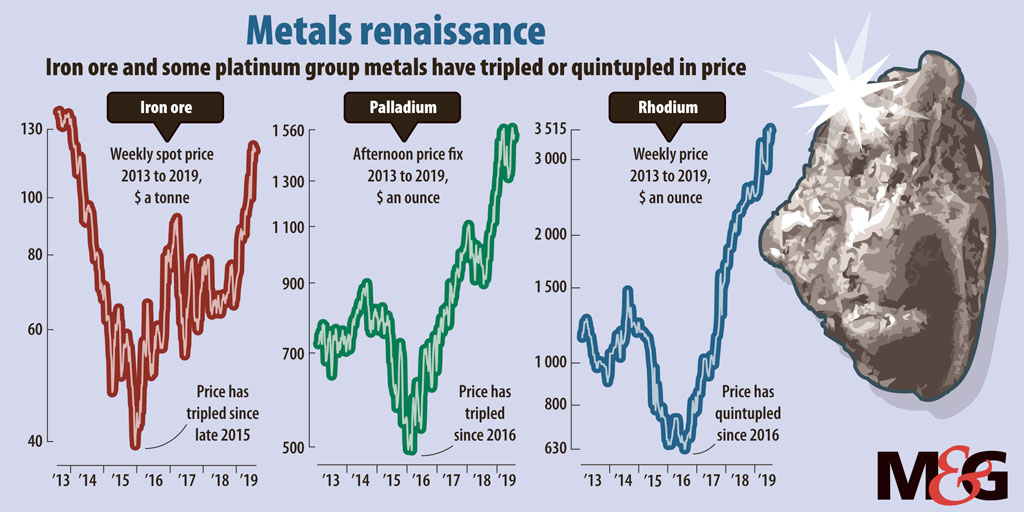

The boom is in no small part thanks to the high prices for the underlying metals that both Kumba and Anglo Platinum produce, analysts said this week, namely iron ore and platinum group metals (PGMs).

This is coupled with some specific features unique to each company’s portfolio of mining assets, such as low-cost mines that are highly productive and produce particular grades or types of metals that have helped to amplify the effects of high metal prices.

But it remains to be seen how long the run will last.

Kumba Iron Ore chief executive Themba Mkhwanazi announced on Tuesday that the company’s net profits had risen to R13.2-billion, triple what it had earned for the comparative period in 2018.

As a result, Kumba’s board declared an interim cash dividend of R9.9-billion or R30.79 a share, Mkhwanazi said. At a dividend payout ratio of 98%, this is above the company’s target range of 50% to 75% of headline earnings. The performance is despite some operational difficulties such as unscheduled plant maintenance at its Sishen operations, which saw production volumes decrease 11%.

Themba Mkhwanazi heads Kumba Iron Ore. (Gallo Images/Sunday Times/Alaister Russell)

Themba Mkhwanazi heads Kumba Iron Ore. (Gallo Images/Sunday Times/Alaister Russell)

Kumba’s performance has been driven by strong iron prices over the last year said Edgar Mafoko, portfolio manager at FNB Wealth. The collapse of fellow iron ore producer Vale’s Brumadinho tailings dam in January, as well as disruptions due to a cyclone in Australia in late March, has hit iron-ore supply, driving up prices, he said. A weaker rand has also helped, he noted, because, like Anglo Platinum, much of what Kumba produces is exported.

“[Kumba is] basically paying out every little bit of profit they have made over this period,” said Mafoko.

According to Peter Major, director for mining at Mergence Corporate Solutions, Vale — the world’s largest iron-ore producer — cut back 90-million tonnes due to the tailings disaster. All iron-ore producers, including African Rainbow Minerals, Assmang, and Afrimat, have benefited from the resultant rocketing prices, alongside Kumba, he said.

Since iron-ore prices bottomed out in 2015 they have increased more than 200% to almost $120 a tonne.

Kumba has also done substantial work to rationalise operations and increase efficiencies in recent years, said Victor von Reiche, a portfolio manager at Citadel. The company noted in its results that it has increased operational efficiency to 67%, and made savings of R460-million.

In Kumba’s case, it also benefits from what is known as the lump premium, said Von Reiche. The majority of the ore Kumba produces is lumpy rather than fine, he noted, meaning steel mills do not have to sinter the iron ore in their production processes.

Another, if smaller, geological dividend is that the ore from Sishen has a low moisture content because the Northern Cape is so dry.

These are all geological attributes specific to its Sishen mine, Von Reiche said, and allow Kumba to benefit on two counts — the high iron-ore price, plus the premium it receives for its product. “It is the ideal produce that a steel mill will look for — it has higher iron-ore content, plus it’s lumpy, plus it has lower moisture content,” he said.

Alongside Kumba, Anglo Platinum also announced buoyant interim results this week. The company increased its earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (ebitda) 82% to R12.4-billion compared with previous period and announced a cash dividend of R3-billion or R11 a share. A key contribution to its performance has been good price fundamentals in the basket for PGMs, which include, among others, palladium and rhodium as well as platinum.

In US dollar terms, the PGM basket prices increased 16% year on year, according to the company. Although the US dollar platinum price an ounce declined 11% this was “more than offset” by both palladium and rhodium prices, which increased 39% and 47% an ounce, respectively, in the first half of the year.

In addition, the rand weakened 15% against the dollar, the company noted, meaning the rand basket price per ounce sold increased 33% during the period.

Under chief executive Chris Griffiths, who formerly headed up Kumba, Anglo Platinum has also seen a lot of portfolio rationalisation, said Von Reiche, and the company has concentrated on its highest-margin-generating assets with the longest life span.

Open-cast or pit mining has become much more attractive and viable in South Africa, Major noted, as it is more mechanised and less labour intensive. In Anglo Platinum’s case, its Mogalakwena mine is an open-pit mine.

Although all platinum miners have benefited from high PGM prices, Anglo Platinum has done so in particular, because it has shed so many of its underground operations, said Major. With Mogalakwena in the fold, Anglo Platinum has the world’s lowest-cost PGM operations, he said.

According to the company, Mogalakwena was hit by Eskom power cuts and minor maintenance shutdowns during the period. But this did not stop it from seeing an ebitda increase of 61% compared to the first half of 2018, and an increase in economic free cash — defined as cash flow after all cash expenses from mining, overhead, marketing and market development, sustaining capital expenditure and capitalised waste stripping — of 81% over the period.

Mogalakwena is also rich in palladium, Von Reiche noted, so has the added bonus of the lift seen in palladium prices. “This is one of the most important mines, by a long way, in [Anglo Platinum’s] life,” he said.

With roaring metal prices a main reason both mining houses are “printing money” the big question is how long the good times will last.

“Iron ore prices at these levels are not sustainable,” said Von Reiche, but he added that how quickly they normalised remains to be seen.

Nevertheless, even if prices do correct, he said, Kumba “sits further down the cost curve” for iron-ore producers and is likely to be able to sustain itself.

Looking at the PGM basket — palladium is a key input into catalytic converters, which reduce vehicle emissions. Despite the lower platinum prices there have been technical difficulties in switching palladium for platinum in catalytic converters. While this is likely to take place in the next few years, the substitution for platinum means prices should not collapse, he said.