Horn horror: Each year about one thousand rhinos are killed in South Africa,and. Photo: Daniel Born/The Times/Gallo Images/Getty Images

About a thousand rhino are being killed each year in South Africa. Rhino species in other countries are being driven to extinction. A sophisticated criminal network is driving this slaughter, which has led to the creation of a vast online ecosystem in which rhino horns and other rhino parts are being sold. With a species at stake, the fightback is being forced to become just as sophisticated.

Law enforcement used to be able to track down physical sales to combat poaching. Now, cyberspace allows sellers and buyers to remain anonymous, and to find goods that might otherwise be difficult to find (often because they are critically endangered), all with just a few clicks.

Sellers sometimes use their real names, but will never give away their actual identity or let any details about their lives slip in casual conversation. Although they have to start somewhere — the part of the internet that is open and accessible to anyone is the usual starting point — these types of interactions often end up on what is called the darknet. Access to this level of the internet requires password authentication, and it includes platforms such as WhatsApp, closed Facebook groups and WeChat.

By having a virtual private network turned on at all times, a seller and buyer might never meet in person. A successful transaction relies on discretion, blind trust and middlemen.

Making payments

When it comes to payment, Western Union is a popular choice. Mostly, this is because you can make and collect payment in cash, so there is no need to worry about involving bank accounts. Senders and receivers both need to present a legitimate form of ID, which is why some traders prefer to have someone else collect payment.

Other global payment platforms, such as PayPal, require a bank account to be linked to them, making transactions more easily traceable, and an undesirable option for illegal wildlife trade.

Sometimes the deals are conducted in person at trade fairs, where everyone operates with cash; often deals are set up online beforehand, through group chats and forums.

This sophistication means that, at the moment, it is possible to get away with illegally trading wildlife online. When law enforcement becomes more sophisticated, the market just goes deeper and further into the hard-to-find parts of the darknet.

Tracking these trades is taking up more and more time for organisations such as the International Fund for Animal Welfare and the global wildlife trade monitoring group Traffic. Their starting point is often an advertisement, for an animal as endangered as a pangolin, for example, placed on an e-commerce platform or social media. While this request is public, responses are not.

Technical innovation

Driven by this demand, rhino poaching in South Africa — home to about 80% of the world’s rhinos — has grown dramatically since 2008. Although fewer rhinos are being poached — figures released by the department of environmental affairs on July 31 showed 318 were killed in the first six months of 2019, compared with 386 in the same period in 2018 — rhino numbers are declining.

This is in part because of how expensive it has become to protect them — right now, a rhino is worth more dead than alive.

John Hume, who operates South Africa’s largest private rhino breeding programme, is reported to have said it costs him at least $5-million a year to protect and take care of his nearly 1 700 white rhinos. The controversial breeder, who is a leading supporter of the legal, international trade in rhino horn, successfully challenged the government’s 2009 moratorium on the domestic trade of rhino horn in 2017. Earlier this year, he claimed bankruptcy and conducted a crowdfunding plea.

Turning to technical innovation to protect endangered species such as rhinos has become the leading approach by organisations such as the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, Interpol and Rhino Coin.

At the beginning of last year, the Global Initiative launched Digital Dangers, a project that aims to better understand and disrupt digitally enabled wildlife trafficking. In partnership with the Center for Analysis of Social Media, it created an online search engine that monitors how, where and when endangered plants and animals, or commodities containing them, are transacted using the internet.

This tool — the dynamic data discovery engine — searches the internet for all mentions of keywords, including “ivory”, “scales” and “horns”. It then separates the relevant results to create a list of URLs where users can find advertisements and conversations of what is potentially illegal activity, such as buying and selling endangered animals.

Project lead and senior researcher Simone Haysom says trying to understand the big picture is what led the Global Initiative to use technology to look at possible interventions. “The internet confounds traditional research methods — you can’t visit physical locations and use face-to-face interactions to understand illicit markets, or examine dockets and trial hearings, because there is so little enforcement of online law breaking.”

Online evolution

Online illegal wildlife trade is always evolving, and has shown an ability to adapt, as long as there is money to be made, says Caroline Cox, a senior lecturer at Portsmouth Law School who co-founded the Ivory Project, which researches and reports on trade in ivory goods among antique dealers and auction houses in the United Kingdom.

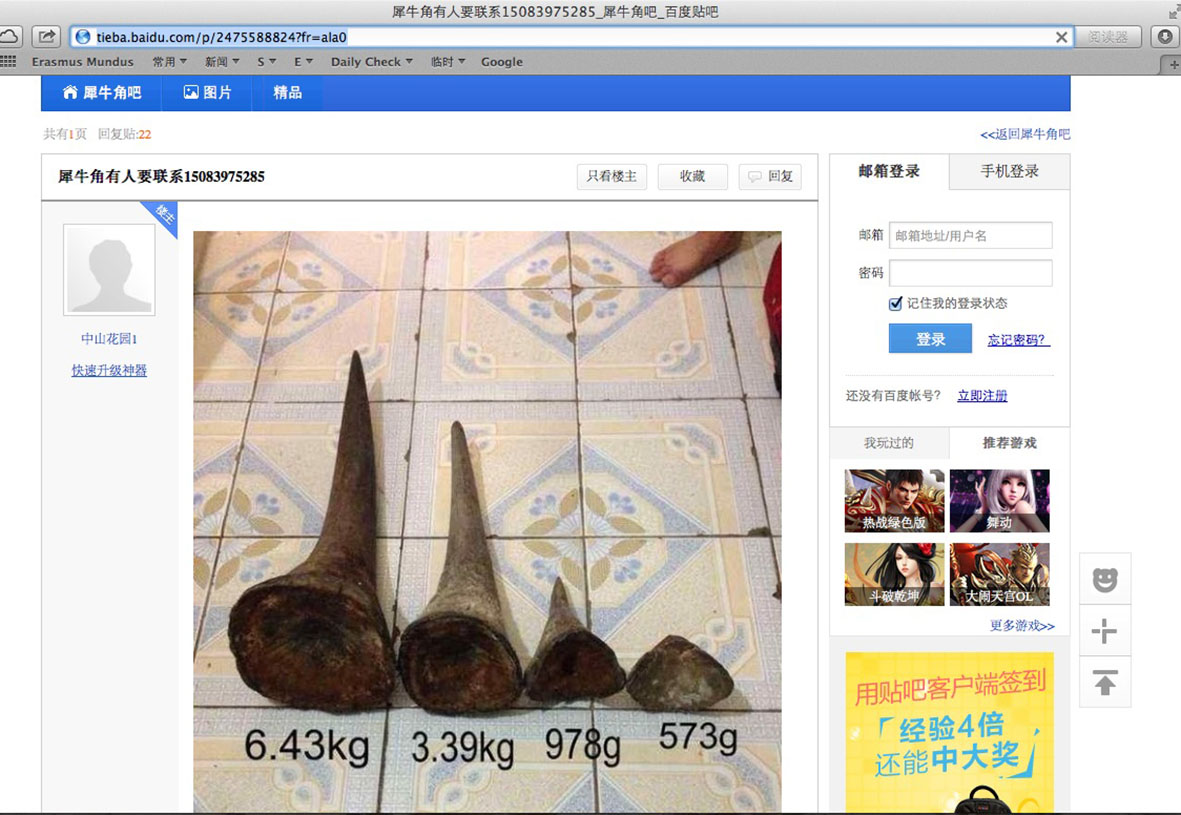

Some rhino horns end up being sold on online platforms such as Baidu Tieba.

Some rhino horns end up being sold on online platforms such as Baidu Tieba.

Increased efforts to disrupt it, while necessary, could force the market on to the darknet, which will in turn require an even greater need for technological interventions, she says.

Cox says disruption will rely, in part, on big online companies stepping up and taking more action: “They have to put in proper, relevant and realistic interventions to see what traders are putting up. All the cards are in their hands,” she says.

This investigation was developed with the support of the Money Trail project. Editorial support was provided by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism