Double agent: Olivia Forsyth, who spied on fellow students, fled to the British embassy in Luanda after the ANC had detained her in 1986 after she offered to spy for them. (Sunday Times)

BETRAYAL: THE SECRET LIVES OF APARTHEID SPIES by Jonathan Ancer (Tafelberg)

TOBACCO WARS: INSIDE THE SPY GAMES AND DIRTY TRICKS OF SOUTHERN AFRICA’S CIGARETTE TRADE by Johann van Loggerenberg (Tafelberg)

Remember the Bulelani Ngcuka debacle? That was when, in 2003, accusations that he had been an apartheid spy issued from the Jacob Zuma camp and led to an official inquiry, the Hefer commission. Zuma had recently been dismissed as deputy president by then president Thabo Mbeki, having been implicated in corruption in the trial of Schabir Shaik. Ngcuka was the director of prosecutions then in the midst of contemplating when Zuma should be charged.

The accusation that Ngcuka had been an apartheid spy came from Moe Shaik, a former ANC intelligence operative (and Schabir Shaik’s brother), but no doubt they originated with Zuma. His modus operandi is to try to discredit opponents, or to distract from cases against him, by accusing others of being spies — as he has recently done to three ministers who served in one or another of his many Cabinets.

Of course it turned out that Agent RS452, whom Shaik et al had claimed was Ngcuka, was Vanessa Brereton, a lawyer who had been involved in the Eastern Cape anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s. She confessed that she, not Ngcuka, had been the apartheid spy. So Shaik, the great ANC spymaster, and Zuma, the former head of ANC intelligence, were wrong — but the corruption case against Zuma was stalled for many years, and Ngcuka left the prosecutor job soon after. Today, facing those corruption charges once more, Zuma throws out more spy accusations.

We are hopefully wiser these days about how Zuma works. But other, allegedly anti-Zuma parties such as the Economic Freedom Fighters have taken a leaf from the Zuma book, and it’s clear from many accounts, such as those of the attacks on the SABC8, that the spooks are everywhere. A state agent was lodged in Lonmin at the time of the Marikana massacre, and another (his wife) worked “diligently”, but under apparent deep cover, at the South African Revenue Service (Sars) and the South African Passenger Rail Agency.

As with the former police crime intelligence chief Richard Mdluli, who spent so much time concocting reports for Zuma to compromise his enemies, there would seem to be a myriad state agents doing the dirty work of those who feel their power is under threat. South Africa is, as one Mail & Guardian front page had it 10 years ago, the “spy nation”.

Brereton is one of the spies of the apartheid era dealt with in Jonathan Ancer’s very readable and informative book, in which he covers spies on both sides of the conflict. They range from Dieter Gerhardt, the naval officer who gave South Africa’s (and its allies’) military secrets to the Soviet Union during the Cold War, to the late Mark Behr, who confessed, soon after he’d won literary prizes for his novel The Smell of Apples in the early 1990s, that he had spied on his fellow students at Stellenbosch University for the security police.

In between, we have the likes of Gerhard Ludi, who infiltrated the South African Communist Party (leading to the life sentence imposed on communist leader Bram Fischer), the “accidental spy” Roland Hunter, a South African Defence Force conscript who fed secrets to the ANC in exile, and the host of spooks who spied on the student left and organisations such as the Black Sash. So many spies got into the student left, writes Ancer, that in a photo of the 16 members of the 1972/1973 Wits student representative council four were agents of the security forces. One was Craig Williamson, perhaps the most successful of apartheid’s spies.

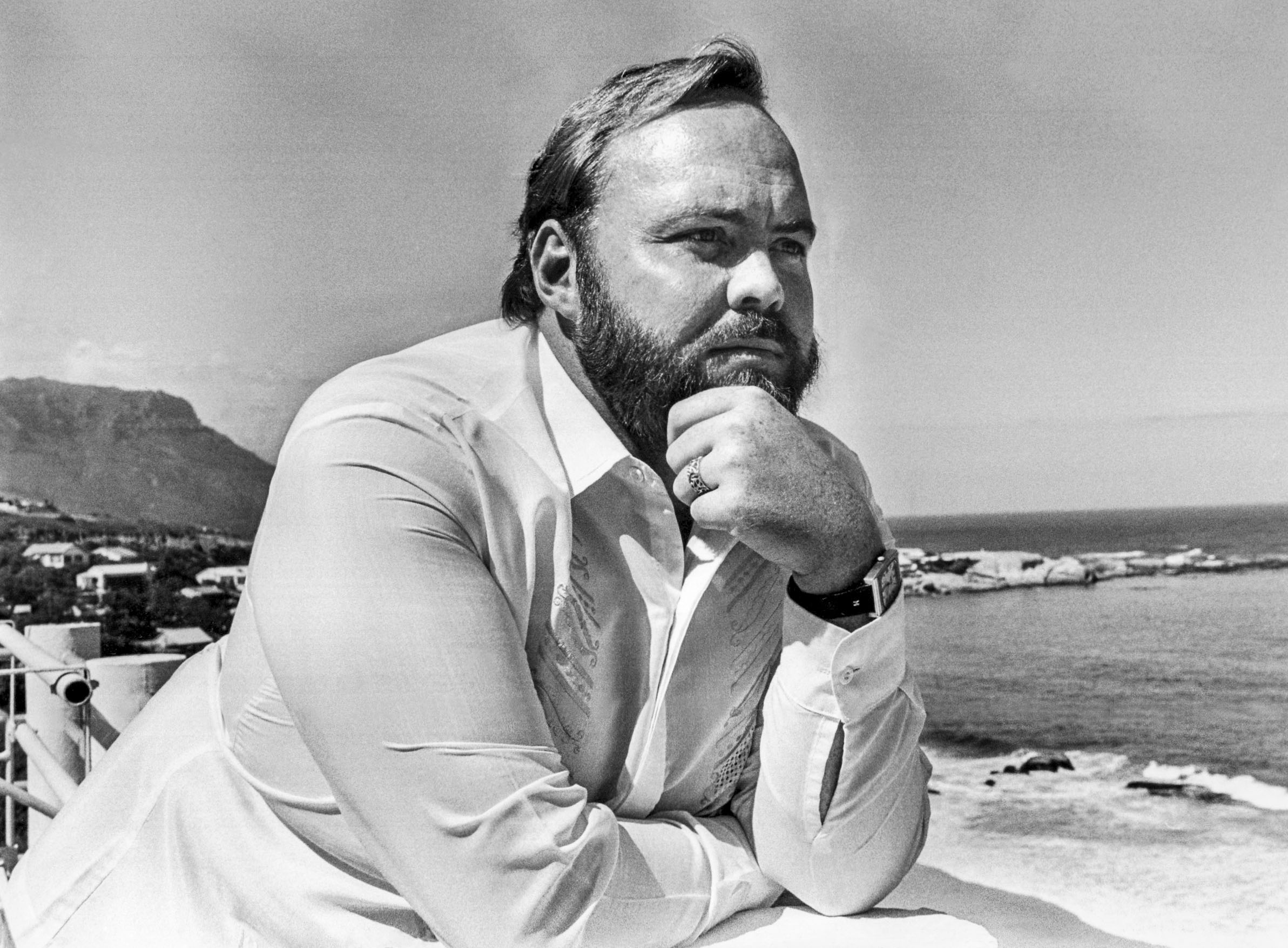

Craig Williamson infiltrated the student left in South Africa and in the international arena. (Times Media)

Williamson then infiltrated the international leftist student-funding body, and was involved in the assassinations of ANC activists Ruth First and Jeanette Schoon. He was the subject of Ancer’s previous book, Spy: Uncovering Craig Williamson. In Betrayal, Ancer writes: “One of the objectives of the book Spy was to try to understand what made Williamson tick and why he did the things he did. After spending three years attempting to understand Williamson’s psyche, I realised that human beings defy being ‘understood’. I would never actually know what made Williamson Williamson.”

Ancer returns repeatedly to the question of what motivates such people and, linked to that, how they may be able to negotiate forgiveness and reconciliation after the fact — that is, if they ever come to any understanding that they did anything wrong. (Williamson doesn’t.) “The motives of people who become spies have been summed by the acronym MICE: Money, Ideology, Coercion and Ego/Excitement,” he writes, before going on to enumerate Gerhardt’s own more complicated formula, which includes those elements plus “flawed character” and “self-satisfaction”.

But that doesn’t fully explain the spies whose careers Ancer details. Money seems a relatively weak motivation for most, and few appear to have been coerced. Seduction certainly played a role for some, especially women spies who fell in love with their handlers. The need to “belong” has a bearing for others, and ideology clearly pushed many into spying, though the strongest motivation seems to be a kind of psychological self-empowerment, the need to feel one has a secret power over others.

Perhaps that secret power enables spies to live lives of deception, to work in parallel, mutually contradictory tracks, and betray their ostensible friends. Some did good work in organisations such as the Black Sash while, simultaneously, ratting on their fellow activists. Others seem to fall into Gerhardt’s “flawed character” category, though in the case of Olivia Forsyth that seems a somewhat paltry description of what begins to look like a kind of borderline personality disorder.

Forsyth spied on fellow leftie students for the security police, dodging the suspicions that swirled around her. Then she popped up in Lusaka, offering to work for the ANC, claiming some kind of Damascene conversion to the anti-apartheid cause. But was she a wannabe double agent? After some confusion on the part of the ANC, she had a spell in detention, then escaped back to South Africa, where she was presented by the apartheid spy bosses as a triumph of spookish derring-do.

Her autobiography, as Ancer points out, fails to explain her motives, or reveal the truth. People she betrayed found her account unconvincing, yet at the time they were taken in by her. Do the deceptions take over, fragmenting the personality or becoming part of its very texture, so that ultimately the individual can no longer tell the lies from the truth? Is there a real person in there? Or is it all a mass of delusion?

Whatever Forsyth’s true motivations, her case looks rather similar to that of a central figure in Johann van Loggerenberg’s book: Belinda Walter, “Agent 5332”, who got involved in what he calls the “tobacco wars” among the tobacco companies and between them and Sars, where he worked then; she also seems to have seeded what became the Sars “rogue unit” narrative.

This is Van Loggerenberg’s third book on Sars; the first, which he published after having left Sars when the Tom Moyane purges began, was cagey about Walter, despite their “affair” having been sensationalised in the Sunday Times’s coverage of the saga. There were legal matters outstanding in relation to Walter, he wrote then; now, he writes in Tobacco Wars, she seems to have disappeared.

Today, Van Loggerenberg is one of those accused in a murky court case against three people who opposed Moyane’s regime, even after the Nugent commission probed the matter and found the wrongdoing to have been on Moyane’s side. The public protector, of course, has recently revived the discredited “rogue unit” story and used it as a weapon to bash Pravin Gordhan, the former Sars commissioner who is now minister of public enterprises and an implacable foe of corruption.

Van Loggerenberg sets out the background with exemplary clarity. The old tobacco giants, under threat from new entrants into the market, engaged in industrial espionage against their new competitors, suborning state bodies and agents.

When she first contacted Sars, shortly before infiltrating her way into Van Loggerenberg’s personal life, Walter was going as the chairperson of the Fair-Trade Independent Tobacco Association (Fita), the body supposedly representing those new market entrants. Later she would claim Fita itself was set up by the State Security Agency as a way “to understand the tobacco industry”. That claim has not been properly tested, and Walter is obviously not to be trusted — she also maintained, at different times, that she was spying for other tobacco interests, and otherwise made many odd and contradictory claims.

The story plays out with a great deal of misinformation and skulduggery; it’s depressing, but also makes for a riveting read. Van Loggerenberg outlines the careers of the key tobacco barons, showing that little in their doings was above-board. It’s not surprising that it all became a game of spy versus spy, that lives were ruined, serious projects to uncover malfeasance were derailed, and the South African fiscus suffered painfully. Certainly, stage agencies were corrupted and used in a devastating intertwining of private and public interests that is, in essence, the pattern of state capture.

And, in a weird process of projection that fits the style of spooks in the Zuma mould, those suborned agencies and their agents’ manipulations became the model of the “rogue unit” narrative. Walter seems to have developed that story, transferring the dodgy activities of her Fita, and other units, into the real investigative Sars unit’s name. She was apparently a rogue unit unto herself.

It’s those who are accustomed to plotting and conniving who tend to accuse others of plotting and conniving; it’s the spooks who see their mirror image all around them.