In 2024, global coal consumption reached a record high, with commercial banks investing more than $130 billion across Asia, the US and Europe.. (Paul Botes)

The taxpayer will be burdened with a roughly R10-billion bill over the next six years, because Eskom has failed to negotiate a standard price for the coal it burns to keep the lights on.

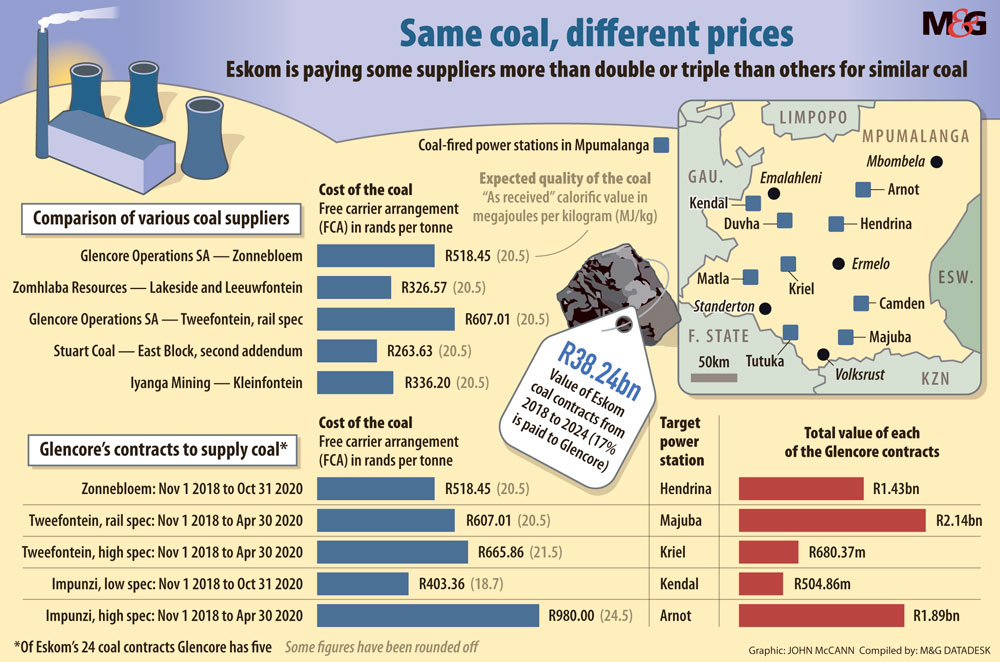

The Mail & Guardian can reveal that Eskom has contracted 16 coal-producing companies to provide it with more than 70-million tonnes of coal in the next six years at a cost of more than R38-billion.

But Eskom could have saved about R10-billion — or nearly R4.5-million a day — had it negotiated a better deal.

Responding to M&G questions, Eskom said it was untrue that it has failed to negotiate coal prices but rather it ended up paying higher prices due to a rapid decline of coal stock.

The cost of the utility’s energy is under scrutiny, with President Cyril Ramaphosa raising the issue in Thursday’s question and answer session in the National Council of Provinces.

Mineral and Energy Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe warned last week: “At these prices of electricity, this economy is going to collapse. You have got to reduce the prices — what we are saying is coal producers must contribute in ensuring that it is actually addressed.”

In part, because of these prices, Eskom lost R21-billion in the last financial year.

Last month Mantashe, Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan and Trade and Industry Minister Ebrahim Patel held “emergency talks” with suppliers, through the Minerals Council, to address the high prices.

The council is made up of industry players in the energy and minerals space.

In a statement to the M&G, the council said last month’s meeting was to deal with the supply of coal to Eskom and “especially to deal with bottlenecks”.

“From a Minerals Council and companies, perspective, due and careful consideration is being given to being mindful of competition regulation. What is important to note is that purchasing coal makes up only around 30% of Eskom’s cost structure, and this figure is even lower than that (around 26%) if capex is considered. And Eskom has agreed that it will be looking at all elements of its cost base.”

Analysis of Eskom’s coal price contracts shows a wide range of prices paid for the raw material — with some companies charging the utility double the price it is paying other, smaller suppliers for the same or similar coal quality.

On average the quality of coal Eskom is buying from the 16 contracted companies is 20.45 gigajoules per kilogram — with an average cost of R409 per tonne.

If Eskom paid this average for the 70-million tonnes, it would pay R28-billion. But, because certain companies charge more, Eskom is now going to part with R10-billion more — which is then passed on to the consumer, or taxpayer.

For example, Glencore is charging R607 per tonne when the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) has guidelines saying it should be R350 per tonne delivered.

Four of the most expensive prices, per tonne, are part of Glencore contracts. The most expensive coal is R980 per tonne and, although this has a higher quality rating, it is still more expensive than similarly rated coal from other firms.

Glencore is charging between R100 and R200 more per tonne, even for coal that has an average quality rating. Other suppliers — such as Iyanga Mining, Zomhlaba Resources and Stuart Coal — price their coal at R336.20, R326.57 and R263.63 respectively.

Glencore spokesperson Shivani Chetram said: “Glencore’s contracts are negotiated on an arms-length basis and are based on market prices and conditions at the time of negotiation.”

In 2016 and 2017 there was an outcry over Gupta-owned Tegeta Exploration and Resources selling coal to Eskom at R20 per gigajoule — which equates to R400 per tonne.

Now, questions are being asked about Glencore and its high coal prices.

One former Eskom executive asked: “Why was it wrong when the Guptas were being paid more and it is now okay when it is companies such as Glencore and Seriti?” adding that if there was no reason to pay such high prices then, why now?

A senior Eskom official, who did not want to be named, told the M&G that the prices varied from one mine to another: “Prices from old contracts were cheaper … emergencies created from 2008 and future years pushed prices up. Transport prices are currently inflated to benefit suppliers with connected officials. Some prices are inflated — claiming good quality coal, which is not true.”

The details of the coal costs come as the treasury sets out specific conditions for yet another Special Appropriation Bill tabled before parliament. This will see Eskom receive R59-billion over the next two years.

This latest bailout follows a R69-billion commitment made in February’s budget speech.

The latest figures also fly in the face of Nersa’s multiyear price determination for the 2018-2019 financial year, which allows Eskom to spend R39-billion for 114-million tonnes of coal.

A breakdown of these figures reveals that Eskom is limited to R344 per tonne without transportation costs — which could add a further R100 per tonne.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Several commentators, including dismissed former Eskom executive Matshela Koko, told the M&G that Eskom only had itself to blame because as the largest consumer, it could negotiate on its own terms.

In a statement to the M&G, Eskom said: “The notion that Eskom has failed to negotiate proper coal contracts, across the board, is misleading … For example, in instances where suppliers are unwilling to divulge their costs, and where there is an immediate need for coal to cover the shortfall, the option of either reducing the burn with the risk of load-shedding needs to be weighed up against paying the higher prices for a shorter duration to alleviate this risk.

“This is precisely what happened during the latter half of 2018: Eskom ended up paying higher prices after protracted arduous negotiations, due to rapid decline of coal stock. There was an urgent need to replenish coal stock in the short term.”