Drama queen: Lebo Mathosa performing at a Missy Elliot concert in 2005 (Lefty Shivambu/Getty Images)

It’s the early 1990s. Kwaito music has our attention. A group by the name Boom Shaka enters the scene through a wavy jam with a slow start. The opening keys of what sounds like a kwaito take on a UFO-like synthesiser ease us into Theo Nhlengethwa singing the first verse. Then in comes another voice: a nasal and sultry vibrato instrument that can be likened to the sound of a cello. Lebo Mathosa doesn’t just sing “it’s about time to listen to Boom Shaka” — she declares it.

In a few days Viacom’s channel BET Africa will premier a six-part biopic on Mathosa’s life. Shortly thereafter, the Old Johannesburg Warehouse will auction off the rights to her entire music output.

To put the biopic together, South African production house Ochre Media partnered with the department of trade and industry, Viacom and the Gauteng Film Commission.

On the biopic’s set, Monde Twala, vice-president of BET Africa, tells the Mail & Guardian that the process of “securing funding, biographical information and permission to use the music” took four years. Dream: The Lebo Mathosa Story is the first local biopic from BET Africa.

The six parts of the series, which will run for 44 minutes each, will remake Mathosa’s journey through themes of migration (being uprooted from her birthplace in Ga-Rankuwa to live in Daveyton), identity discovery (through intimate relationships) and democracy (the narrow freedom to move between different socioeconomic settings).

Speaking to the M&G, the biopic’s director, Portia Gumede, says that the plot focuses on the life experiences that moulded Mathosa’s artistry. “We kept clear of tabloid or mythical driven narrative, however, there is no avoiding unearthing the unknown — tastefully — which we believe we did well,” Gumede says.

The Universal Music Group confirmed that it currently owns the rights to Mathosa’s music. Although the Old Johannesburg Warehouse could not give M&G an exact date for the auction, it says its staff are currently collating a song catalogue and compiling a report on annual record sales and royalties. When the auction does commence, any South African with the budget will have the chance to own Mathosa’s music.

As the memory of Mathosa is being refreshed in the collective mind of South Africa, the M&G attempts to reimagine, or rather, recanonise her at a time when our everyday sociopolitical lexicon is ready to archive the trajectory of such a grand figure.

With only 12 years on her career clock — Mathosa died in a car crash in 2006 — a lot had to give for her to rise to and maintain an immortal level of stardom that is still being referenced today.

Listening to Lebo

Following our It’s About Time introduction to Mathosa, we continued to heed the call to “listen” when Boom Shaka officially dropped their eponymous debut in 1994, all the way to the later albums that featured tracks such as Thobela and Gcwala.

There was also the memorable 1998 South African Music Awards (Samas), at which they offered a reprise of Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika. During this performance Boom Shaka turned the prayer-like number into a groove by pairing the lyrics with a dance beat that encouraged a get-down. Although some people, such as writer and black pop archivist Bongani Madondo, perceived it as an attempt “to free [the anthem] from its struggle history slumber”, others found it irreverent.

Lebo Mathosa with Boom Shaka bandmate and friend Thembi Seete (Oupa Bopape/ Gallo Images)

Mathosa’s publicist, Marang Setshwaelo, can attest to such reactions, having to deal with the press and their “knee-jerk instinct to just report on how outrageous” any project that featured Mathosa was. But the singer paid it no mind and would clap back with statements such as the one in her 2005 best dance album Sama award acceptance speech. “I’ve always been controversial and I’ll remain so,” she said at the time.

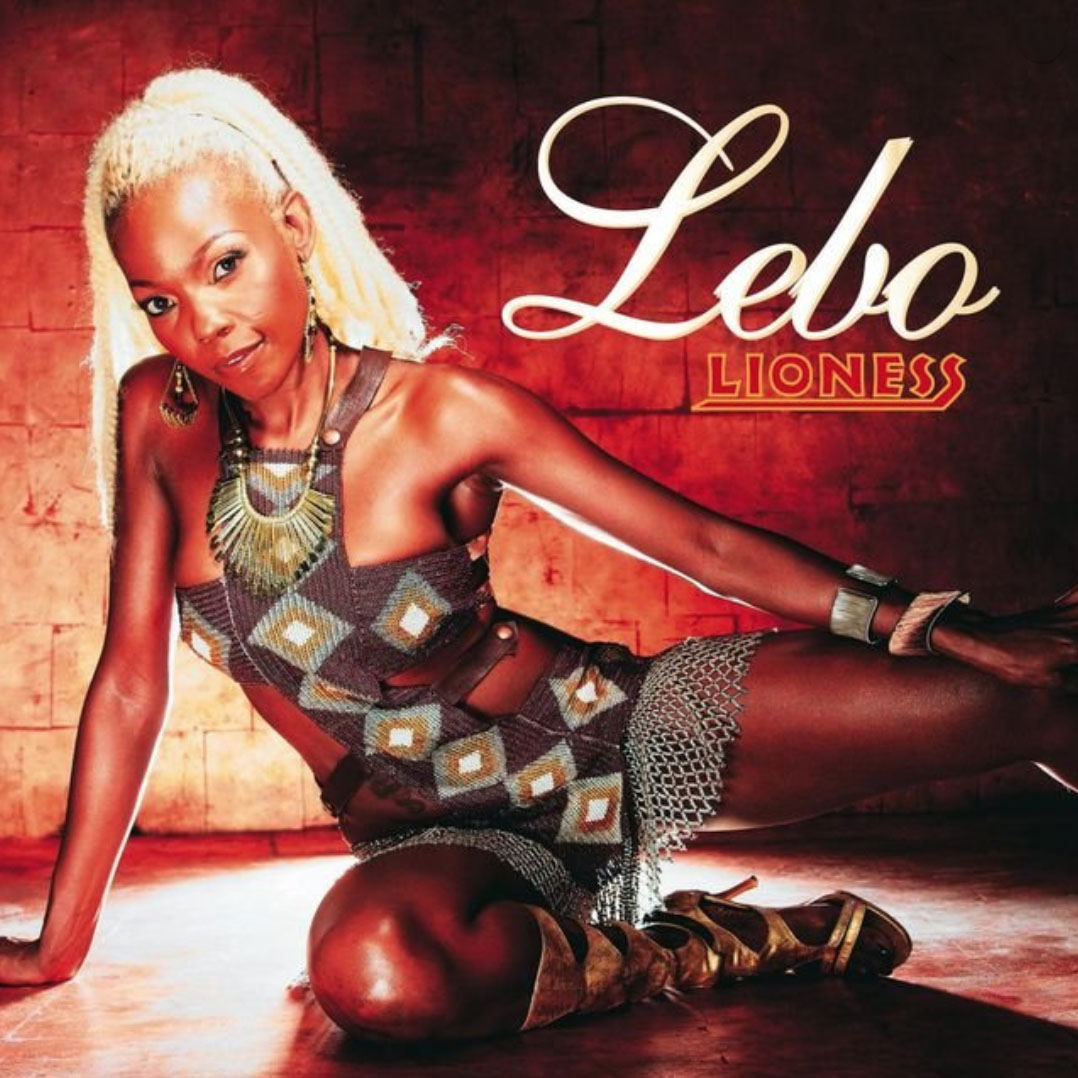

And so the saga continued when Mathosa the solo artist gave us Dream (2000), Drama Queen (2004) and Lioness (2006). The solo discography earned her Samas for best dance album, on two occasions, as well as best dance single and best female vocalist.

If awards are anything to go by, such appreciation seems inevitable when considering her range. Mathosa had so much talent to draw from, she was able to offer us the reggae-esque Dangerous in the same breath as the kwaito-meets-R&B mantra I Love Music in the genre-bending Drama Queen.

And although the tracks on her debut are not revisited as frequently, singles such as Spiritual Freedom show off the reach of her subject matter as a songwriter. In it Mathosa touches on getting lost in the maze of capitalism by singing, “Never ever let success or evil alienate you/ Remain you, the real you/ Stay true to yourself/ Be an example of perseverance and dedication.”

Looking like Lebo

With regards to her sartorial canon, we watched Mathosa go from a carefree teen to possessing unyielding allure. As the lead of Boom Shaka, her and Thembi Seete’s matching looks won the hearts of trend-chasers and continue to do so today. Public figures such as DJ Doowap and Nomuzi Mabena sport the same waist-length braids in high ponytails, sports-bra crop tops, high-waisted latex pants and Doc Marten boots.

“Boom Shaka is a major influence in my craft and hairstyles,” DJ Doowap told Superbalist. “They used to perform and party at the nightclubs my parents owned and would sometimes come over to my house … I would always be in awe of Lebo Mathosa and her incredible self confidence.”

When Mathosa went solo, her curly platinum-blonde hair, thinly tweezed brows, hazel eyes and less-is-more aesthetic was the moment when Brenda Fassie and Madonna met Beyoncé from ekasi.

Witnessing Lebo

When asked about Mathosa’s presence on stage, Setshwaelo says the only way to describe her is by likening her to a “woman literally possessed” because she performed free of the inhibitions of virtuous womanhood.

There’s a 2001 video of Mathosa performing as a part of a Marianne Fassler South African Fashion Week show. Wearing a red, low-cut corset and a matching, sheer, thigh-high slit skirt, Mathosa oscillates between isipantsula and a belly dance routine. She kicks, squats and winds her waist with an endearing smile on her face, never losing her breath. With nothing on the stage but a swing that she occasionally sits on, she keeps all eyes on her.

Lebo Mathosa performs on stage as part of “MTV Base 100th Live!” at the Ster-Kinekor Top Star Drive-In on April 20, 2005 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Bruno Vincent/ Getty Images)

And this performance wasn’t an outlier. No matter the crowd or the event, Mathosa’s mission was to capture he audience. When asked about her most memorable Mathosa performance, Setshwaelo remembers her being given a three-and-a-half-minute slot at the 2006 Kora All Africa Awards. “For the first minute, the audience was dead silent with open mouths. For the remaining two-and-a-half minutes the crowd got to their feet and roared,” Setshwaelo laughs.

For this magic to happen, Mathosa insisted on being hands-on with the execution of every performance. Setshwaelo remembers her customising every dancer’s outfit or fighting event co-ordinators for the best sound and lighting. Those who witnessed her process closely say the price Mathosa had to pay for her uncompromising commitment to her art was coming to terms with being labelled “difficult” or “bitchy” for wanting things done her way.

Understanding Lebo

Considering the above recollection, there’s a national consensus in line with Twala’s opinion that “if the world puts Rihanna or Madonna up, we’ll bring Lebo”.

Over and above her sonic, social and aesthetic legacy, the likes of Madondo refer to Mathosa as an “activist” because of the level of ownership and independence that she was able to negotiate at a time when it was unheard of among her peers.

Speaking about when she began working with the icon as her publicist, Setshwaelo recalls how Mathosa “released her debut album, completely self-financed”. By so doing, she was able to secure full publishing rights and ownership of her work.

Yet, the activist label extended beyond matters of ownership. The visible nature of Mathosa’s intersectional existence was also activism.

It was in her openly but never declaratory bisexuality, her ghetto-fabulous take on R&B, her unapologetic style and taking control of her sensuality.

“Not to fetishise Mathosa as though she was staggeringly unique, or as though she was a celebrated queer feminist above all,” says Madondo, “[But] her struggles as a black woman finding her artistic mojo and her personal identity on the streets and club scene of Sin City were real … not merely performance.”