Puo ya pelo: Eileen Elizabeth Pooe comes from a family of educators, but her love for her mother tongue sets her apart.

Whether incomic books, novels or academic work, African languages are increasingly becoming the norm. Athandiwe Saba takes a look at different projects that are getting more locallanguages into print

The doctor who got her Phd in Setswana

The work of prolific and well-known African authors such as Sol Plaatje must be decolonised.

Eileen Elizabeth Pooe, a lecturer at North-West University, postulates that simple translation from English into an African language does not suffice. Instead, these works must be reimagined and transcreated.

Pooe has made history at her university. Last month, she was conferred the first doctor of philosophy in languages and literature, in Setswana. Her thesis was written in her home language.

Her parents, siblings, husband and in-laws all ended up being involved in education of some sort. Education seemed locked into her being. But her love for her language, Setswana, has set her apart.

She says: “This culture of South Africans not being a reading nation is a notion that I do not agree with. Once you write our stories in our African languages — in a way that addresses our concerns and challenges in our daily lives — I am telling you [that] people will put money aside and buy books.”

She is referring to books such as Mhudi by Sol Plaatje. Published in 1930, it was the first novel by a black African to be published in English.

Pooe’s thesis, which has brought her into the limelight, is the first-ever Setswana PhD in the department of Setswana’s 39-year history.

Pooe sees herself as a “Rustenburg girl” who grew up in Phokeng. Her parents were teachers. Her father started what is today called as Motsweding — a mainly Setswana radio station. “I remember I used to say, ‘I don’t want to go into teaching, I want to be a nurse.’ And they looked at me and said the choice was mine. But a few years later I ended up emulating them and became a teacher.”

Pooe’s thesis, which she believes is an ode to her work over decades in education, was written entirely in Setswana and titled “Taoto ya Phetsolelo ya Mhudi ka Sol T Plaatje mo Setswaneng jaaka mmusetsagae wa dikwalo tsa Maaforika tsa Seesimane.”

Pooe tells the Mail & Guardian that Mhudi is an example of a novel that was written by a Motswana, about Batswana — but in English, a language that the people who he was writing about could not read.

She adds that the novel should be transcreated and not simply transcribed from English to Setswana, taking it out of the colonial English language into the language of the author.

“Instead of simply transcribing the work, how about we contextualise the settings, the idea, the mind of the author when he was writing this in an English text being an African,” she says.

“I focused on how we could create the text afresh, as if it originated from that language. Hence transcreation, for repatriation is so important. We are taking them out from the colonial era into the postcolonial era,” she notes.

Pooe believes her work is vital to how Africans see themselves in their languages and this could be a step to getting the nation to read more.

Five things about Eileen

Favourite food when she was writing her thesis: My husband prepared a protein sandwich for me every morning with avo, eggs, sardines, cheese, and coffee. It was only on Wednesdays that I would eat traditional soft mabela porridge.

How many books do you think you read during the course? I am not sure … possibly more than 100, which would include small articles that appeared in newspapers about why mother-tongue education is best, African renaissance begins with languages and [such topics]. Such articles were nutritious for my mind.

Favourite downtime activity? I love my garden — both vegetable and flowers. I eat from my garden and have fresh flowers from it. But I have also become quite the addict of Skeem Saam and Isidingo.

Favourite fiction: I had no time to read fiction. I only read newspapers during the weekend. But now I have lots of fiction books I need to get to reading.

Favourite holiday destination: Victoria Falls is the most beautiful place I know. I have been there twice and I would love to go again.

‘Children should own 100 books’

Book Dash is an innovative way to get 10 children’s books written, illustrated and finished in just 12-hours — and then translated into all South Africa’s languages, ensuring that by next year, one million books are in children’s hands.

The project brings together volunteers who are professionals in the publishing space — including illustrators and writers — and puts them under one roof for 12 hours to create beautiful African children’s books.

The initiative’s Julia Norrish says: “The founders have all been in the publishing industry and they were really frustrated by the fact that the traditional, market-driven publishing models couldn’t provide high-quality and affordable books for all children in South Africa and, obviously, in mother-tongue languages as well.”

Research has shown that the presence of books in the home has a significant effect on propelling a child into education, so Book Dash wants to ensure that more children have books in their homes.

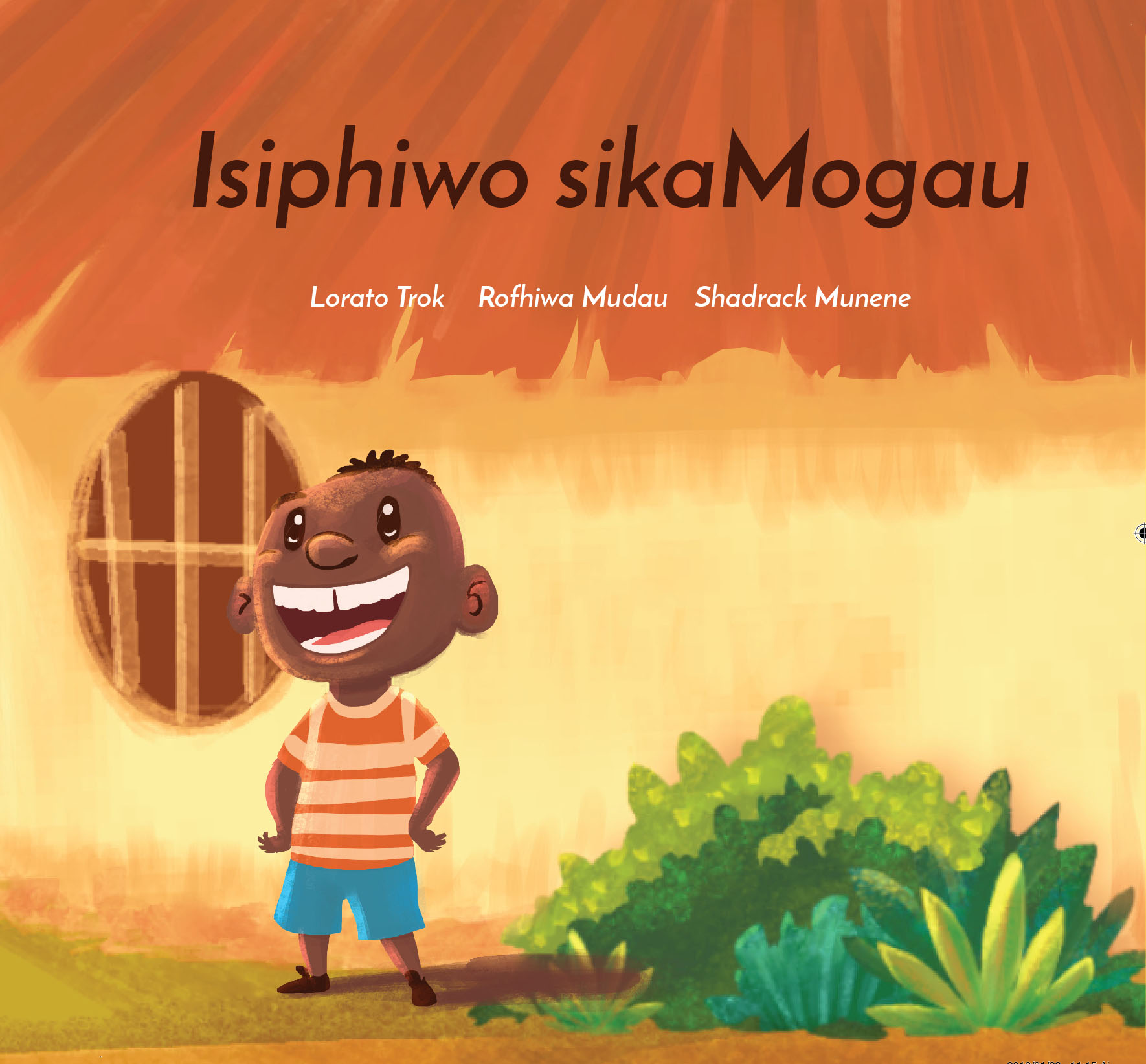

Write it and they will read: Here is one of the more than 128 books created by Book Dash volunteers. Most of the books are translated into all of South Africa’s languages and are free to download from the project’s website.

Write it and they will read: Here is one of the more than 128 books created by Book Dash volunteers. Most of the books are translated into all of South Africa’s languages and are free to download from the project’s website.

Norrish also notes that it’s very difficult to change reader behaviour by dictating that parents should read more to their children, when the same parents can’t afford to buy books. Because the structure of the initiative is volunteer-based, at least 80% of the costs of creating a book are shaved off the price.

As a result, each book costs between R10 and R20.

Book Dash is aiming to get people who have the money to buy a bunch of books to do so — and then donate them.

To date, Book Dash has created 128 original titles, and it has printed and distributed 660 000 books to children.

Many of the books are also translated and are free to download from Book Dash’s website.

Norrish says: “Our overarching vision is for every child to own a hundred books by the age of five, which people think sounds expensive but that’s only because we think of books costing a hundred bucks to R200 each. If we can think of books costing R10 each, then R1 000 a child over five years is not excessive at all. And that’s the model that is genuinely possible.”

A truly African superhero

Next year marks six years since the country was swept up by the homegrown comic book Kwezi. According to the author, Loyiso Mkize, the books will be moving to the next level. “I can’t say much about it but all roads lead to 2020. We are moving into the next natural progression of the book, which is animation,” he says.

The artist tells the Mail & Guardian that they are also on the verge of publishing the best-selling comics in all the official South African languages. For now, they are published in isiXhosa, isiZulu, Setswana and Sesotho.

Comics for the continent: Collector’s editions of ‘Kwezi’, created by artist Loyiso Mkhize.

Comics for the continent: Collector’s editions of ‘Kwezi’, created by artist Loyiso Mkhize.

“We decided to look at the more practical steps of the literacy level of Africa and where the disparities lie in the translation of material and information. We have to produce material that integrates information in all languages and not only Isilungu [English] because it is expedient,” Mkize says. “I am from a small town, eGcuwa, in the Eastern Cape, which predominantly speaks isiXhosa. With the world moving at such a fast pace, I don’t want who we are and our culture and languages to fall by the wayside.”