(John McCann/M&G)

COMMENT

It was Claus Schwab, founder of the World Economic Forum, who coined the term fourth industrial revolution (4IR). I prefer not to use the term because it is alienating to some in the field of education. I rather talk to educational implications of a fast-changing world, which is becoming unpredictable and complex to navigate because of the exponential pace of technology developments and the pervasiveness of information. Some use the acronym Vuca as shorthand to characterise this world — volatile, unpredictable, complex and ambiguous.

Given this reality, what should higher education curricula focus on? I address this question from a learning sciences perspective. Given the pace of change and the unpredictability of technological advances, it is not possible to prepare students comprehensively for this world. It is likely that young people who enter higher education today will have many occupations in their lifetime. It is not feasible to adapt higher education curricula to consistently reflect the ongoing changes in society. And even if it were feasible, what purpose would it serve? Curricula will (consistently) remain outdated.

Some would claim that knowledge is becoming less important because search engines enable access to any knowledge. A speaker at a conference who claimed this, demonstrated this by googling on her smartphone a complicated question in her field of expertise. She said we would not need to store knowledge in our memories in the future, and therefore education should focus less on knowledge and more on what is referred to as 21st century skills. I asked how she knew what question to ask. Surely she drew on her personal knowledge. I also argued that one should distinguish between information and knowledge.

But it is indeed the case that higher education institutions still focus on transfer of information in teaching. Why this still happens and why students are required to memorise large amounts of detail when information about any topic is instantly available on the internet is a valid question. But knowledge remains important. Thinking relies on what one knows, your personal knowledge (stored in memory and activated in working memory).

Critical thinking entails, inter alia, reasoning, making judgments, weighing evidence for claims and considering alternatives. To do this, one uses what one knows, drawing on a personal knowledge base. Thinking creatively often results from grappling with incongruities in what one knows, or connecting seemingly disparate aspects, or applying one’s knowledge in innovative ways or novel situations. Domain specific knowledge (what students know and understand in a given field) and skills (how they use that knowledge) are intertwined.

This resonates with the view that higher education should ideally be producing T-shaped graduates. T-shaped people have specialised knowledge in one area (the vertical part of the T), but they are also capable to team up in other fields (the horizontal part of the T). The latter requires the ability to think critically and creatively and to collaborate and communicate well with others (the 4Cs). Professing the significance of these skills is hardly new. What is new is that success in a Vuca world will depend on the ability to employ them. Also, learning these skills has generally been left to chance because they are not embedded intentionally, systematically and comprehensively in teaching and assessment practices.

What then should students learn to best prepare them for the now and for the future? This question places the focus on learning, instead of content. One could argue that this is purely semantics. And it is impossible to predict and guarantee what students will learn. But I am convinced that placing learning central to teaching, instead of content, sharpens and focuses thinking about the curriculum. It assists with moving away from curriculum coverage, which is deeply ingrained in education.

Though my focus here is on the curriculum — the what of learning — the quality of learning is dependent on both the what and the how of learning: the what and the how are intertwined. I therefore also address teaching practices required for fostering deeper or meaningful learning, the type of learning that enables transfer.

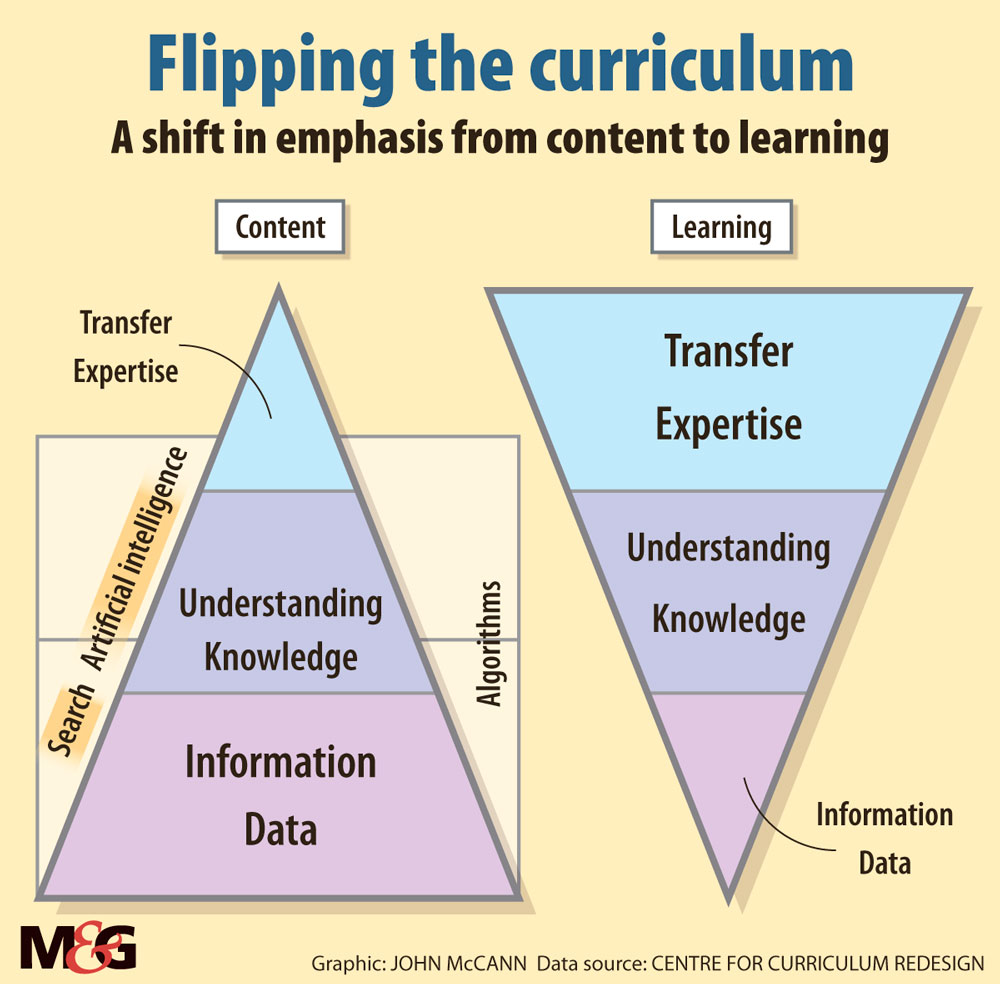

I find the graphic representation of the Centre for Curriculum Redesign useful for guiding thinking about the curriculum for a Vuca world.

In an age of artificial intelligence and ubiquity of information, information as a curriculum focus is senseless. And surely the goal of higher education is not that students should know a lot of information. We want them to have knowledge for meaningful and productive thinking and action. They need understanding and knowledge for expertise and transfer. Transfer refers to the ability to think with knowledge and to use prior learning to support new learning and use prior learning for application and problem solving in relevant contexts. The ability to use prior learning to support new learning is crucial in a fast changing world that requires lifelong learning.

So what does all this mean for curricula? First, knowledge remains essential, but should be curated for relevance. Questions that may help with curation include: What are the essential elements of a given field of study or discipline that students should learn? What knowledge is essential to the type of thinking we want students to do in a knowledge domain? What are the key concepts, processes, methods, tools and skills that are likely to matter in the (work) lives that students are likely to live? Here I borrow from the cognitive scientist, David Perkins, who refers to lifeworthy knowledge. How often will the concepts, processes, methods, tools and skills serve to inform thinking, decision-making and action in the lives that students are likely to live? To what extent do they have the potential to remain significant over time?

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

The type of learning that should be fostered for the developing of expertise and for enabling transfer is referred to in the literature as deeper, meaningful learning. Deeper learning enables students to develop expertise in a particular knowledge area, coupled with an understanding of when, how and why to apply what they know. It enables students to recognise when new problems or situations are related to what they have previously learned, and how they can apply their knowledge and skills to these problems or situations. This is the essence of transfer.

The important point to make here, drawing on the writings of James Pellegrino, distinguished professor of congnitive psychology and of education at the University of Illinois, is that deeper learning is not a product, but the process through which individuals develop transferable knowledge.

Transfer does not happen automatically. Teaching should focus intentionally and systematically on fostering deeper learning. This implies guiding students to relate new ideas and concepts to their previous knowledge and experience, look for patterns and underlying principles, make conceptual links within the domain and between differing contexts, and reflect on their own understanding and their process of learning (meta-learning). It also involves extensive practice in familiar and unfamiliar contexts with ill-defined problems aided by explanatory feedback that helps students correct errors and misconceptions. Multimedia learning environments and artificial intelligence applications used purposefully open many vistas to enable this.

Fostering deeper learning is time consuming. It cannot be done in a crowded curriculum.

But my experience has taught me the appropriateness of Perkin’s assertion that curriculum often suffers from a crowded garage effect: it generally seems safer and easier to keep the old bicycle than to throw it out.

Ridding the curriculum of this requires willingness to prune the curriculum to make space to foster deeper learning and to infuse crucial 21st century literacies such as information and data literacy. Doing this is challenging because it compels trade-offs that are often uncomfortable. But as the cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham reminds us — not choosing is still making a choice. One is choosing not to plan for student learning.

Professor Sarah Gravett is the executive dean of the faculty of education at the University of Johannesburg