Unison: Girls living in Lavender Hill

Every five years I squirrel away everything I can find on the changing contours of civil society, and then try to make some sense of it all in relation to larger trends in politics and culture. It’s always tough because the universe of voluntary, collective action and interaction isn’t a “thing” that is static or owned by one particular geography or ideology; it’s constantly being contested and reshaped in theory and reality, though there are always some dominant themes. Last time it was the effect of the digital revolution. This time it’s polarisation.

But beyond these obvious headlines, the task has become especially difficult for two other reasons.

The first is that the contexts in which civil society operates have become much more hostile. In most parts of the world, people are increasingly divided. Violence, intolerance and inequality are on the rise. Authoritarians of different stripes have gained a foothold. Restrictions on freedom of speech and association are increasingly common, with just 3% of the world’s population living in countries where civic space is defined as “fully open”. Public spheres seem incapable of addressing any of these concerns.

The second reason is that civil society itself is implicated in these trends, because the fractures in society are being replicated in the composition of associational life and the structures of communication. So, we have to accept that civil society is also part of the problem and respond accordingly.

In practice?

Over the past 50 years or so there has been an important change in the types of groups that people typically form and join to pursue the interests that concern them.

Those that represent a particular position, identity or interest have grown dramatically, usually as intermediaries under the control of professional staff and boards, but sometimes as social or protest movements. By contrast, groups that attract a diversity of members in terms of class and political affiliation — and which manage their own affairs democratically — have suffered a major decline. In the United States, for example, parent-teacher associations (PTAs) lost 60% of their members in the decades after World War II.

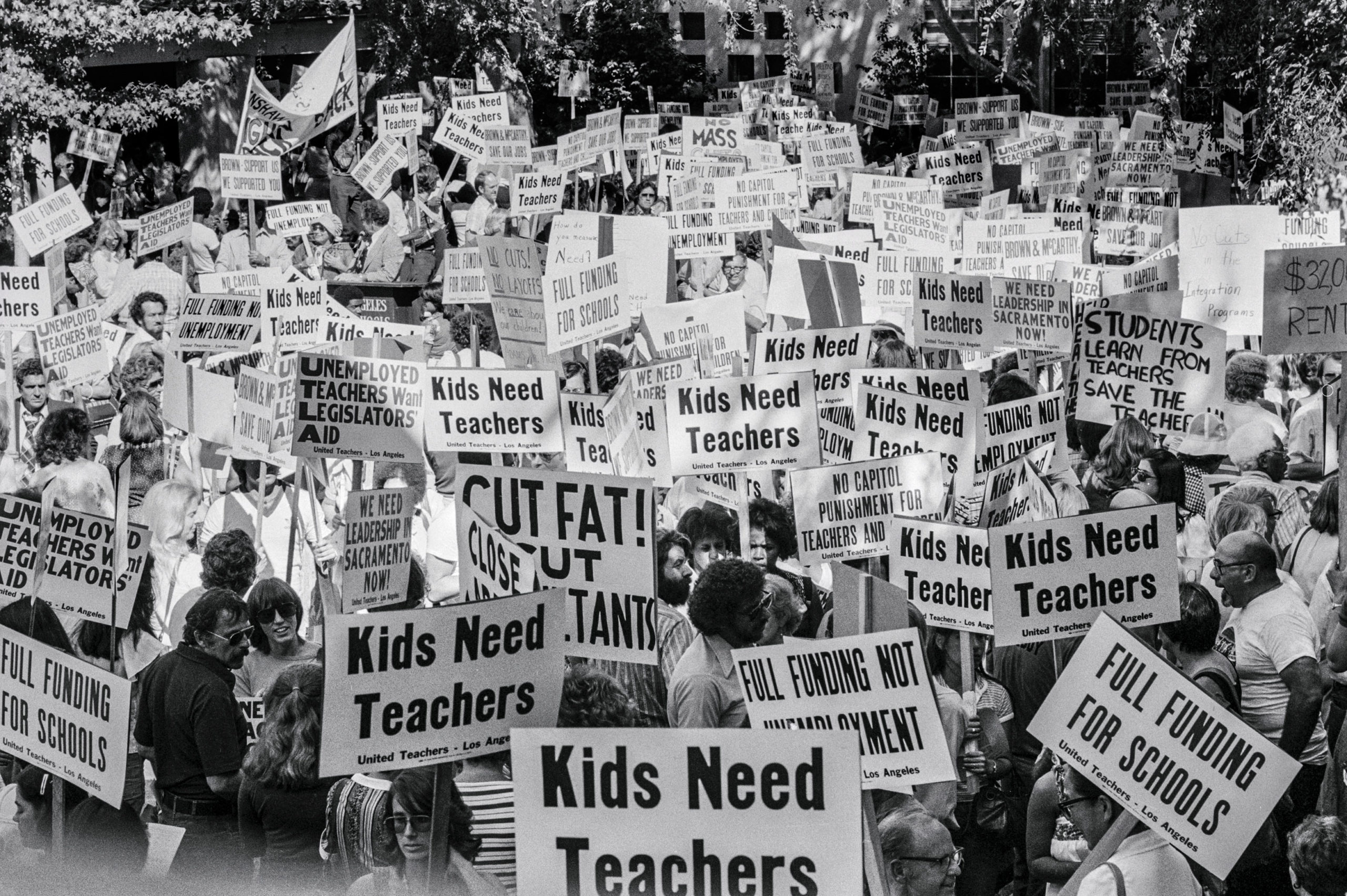

Crossing barriers: People of different views unite for a common cause. Teachers, parents and children protest in Los Angeles against funding and job cuts in schools. (Gallo Images)

This difference is important because, whereas advocacy groups and protesters argue for a particular stance on a particular issue, groups such as the PTAs are able, albeit imperfectly, to argue through those stances to identify the interests they hold in common.

Identifying shared interests is crucial to generating social norms such as tolerance and respect for democracy and the truth, and for identifying long-term societal priorities such as protecting the welfare state. Those things require a consensus across society so that they have more chance of surviving the merry-go-round of electoral politics.

It’s not that advocacy groups and protests are bad — quite the contrary. The problem comes when they dominate the civil society ecosystem to the exclusion of cross-cutting organisations, because one can’t substitute for the other. As conservative think tanks, lobbying groups and media outlets have grown to match their counterparts on the left, this issue has been thrown into ever sharper relief.

All these groups are part of civil society (except for hate groups that deliberately aim to destroy the rights of others to participate), but few are engaged in bridge-building. Simply put, there are now too many special interests in civil society, and not enough common interests or spaces where they can be negotiated, and that’s a significant factor behind the rise of cultural and political polarisation and the problems it creates.

How to turn this around?

Civil society is only one of many influences on trends such as polarisation, but there are some things that could help. The first is to address the disappearance of opportunities in civil society for people of different political views and identities to debate, strategise and organise with one another.

That can’t be done from the top down by funding yet more intermediaries or campaigns to tell people they have to get along; it has to be done from the bottom up so that people take charge of the process of grappling with disagreement at a scale they can manage, and where solidarity means something concrete — where the incentives to act in the common interest are more powerful.

At higher levels of the system among politicians, lobbyists and professional manipulators in the media the incentives are reversed, because they benefit from more division, harder boundaries and a greater fear of difference. But if you take the lid off the pressure cooker and turn down the flame, then local level and other civil society processes have more chance of building bridges over time, without having to force people to jettison all their different identities or beliefs.

Members of the Black Sash movement demonstrate in the streets of Mmabatho against apartheid. (Gallo Images/Rapport archives)

Groups such as the Skills Network in south London and the Belfast Friendship Club show what can be done when these conditions are present. Members of the Skills Network include both leavers and remainers on the question of Brexit, middle- and working-class women, immigrants and those who have lived in the area for generations, but they all agree to work through their differences in a spirit of solidarity. As they put it, “Standing shoulder to shoulder with people across our differences and creating new understandings and visions together is where the real transformative potential lies.” The key is to encourage people to work together on common projects where both success and failure are shared, because it is difficult to sustain deep enmities if you depend on each other for success in addressing issues that concern you.

Second, we need to invest in public spaces of all kinds where people can meet and “not draw the knife”, as civil society scholar John Keane once put it in defining the essence of this idea. Difference and diversity are not the enemies of civil society, they are strengths. What’s problematic is the absence of mechanisms to sort through these differences and reach some common ground.

Traditionally, civil society theorists have seen polarisation as something that can be managed through an active and democratic public sphere that enables such common ground to be debated and negotiated, made up of real and virtual spaces at many different levels — local meetings, community radio, grassroots newspapers, reading and adult education groups, trade union branches and websites, clubs and societies. But when the structures of communication are themselves privatised and fractured, this is more difficult.

One of the most alarming features of politics and organising today is the extent to which these public spheres have ceased to operate, or perhaps even to exist, as people of different views imprison themselves in mutually exclusive social media bubbles and sources of information — or fake news, depending on your point of view. Independent and citizen-controlled media are growing, but they are out-competed by much larger and wealthier commercial platforms such as Facebook, which have contributed to the problem.

There must be places that are not dedicated to making money or accumulating power if civic values and relationships are to take root — places where we can meet each other for conversation and shape a collective course of action in line with our own democratically derived priorities. That possibility, at root, is what is threatened by current trends.

‘You can never leave’

Ultimately, there is no recourse to theory or to history if the problems of civil society are to be fixed — that’s our job as citizens. To do so, we have to be willing to leave the comfort zones of left and right and re-democratise a civic life that has been taken over by experts and intermediaries. We have to see others as co-creators of something larger, even when we disagree with the details of their beliefs.

And we have to develop the sticking power to stay in relationships when they get messy. As journalist Margaret Renki put it in The New York Times, it’s like being “at the most uncomfortable family reunion ever, and you can never leave”.

So, if you work or volunteer or serve on the board of a local organisation or a charity, an independent media group or a library, a university or a think tank, a local council or a church or a mosque, it’s worth asking what you are doing to foster civil society in this deeper sense — not just using it as a vehicle to build your own brand or advocate your particular message or constituency — and to adjust your plans accordingly.

Anything that brings people closer together rather than forcing them apart will help. Anything that generates honest conversation instead of fake news and propaganda can move us forward. Anything that enriches the quality of life rather than diminishing it deserves our attention. These are all ways to build a civil society that’s worthy of the name. The rest is up to us.

Michael Edwards is the editor of Transformation. This is an edited version of an article that was first published on Open Democracy