(Sebabatso Mosamo/ Sunday Times)

COMMENT

I was recently asked to speak at the opening of an evocative photo exhibition at the Durban Art Gallery. It was curated by Chantelle Booysen, a global ambassador for mental health, and titled the Empathy and Hope Project.

The photos were windows into subaltern worlds, usually unseen or ignored: mental illness, loss and loneliness, refugees, homeless people, drug addicts. Heavy stuff. As I stood in front of these photos, imagining lived experiences so different from my own, these portals to empathy invited me to think about hope. Somewhere, somehow, people muster up the hope to continue living — how and where do they find it?

As a psychologist, I find myself forecasting hope for a living; helping people open umbrellas when angst comes drizzling down, before their existential malaise crushes wretchedly like a thunderstorm. It’s not easy seeing silver linings in clouds of despair. But it’s there. It has to be. Our survival — and our humanity — is proof of it.

History shows us that each generation faces some catastrophic event or state that makes the possibility of tomorrow seem almost unreachable — whether the two World Wars, the Holocaust, apartheid, so-called “Spanish” flu (it acutally originated in the United States), Russian flu, the plagues, smallpox, cholera, yellow fever, HIV, Swine Flu, Ebola, and now, Covid-19.

Hope must be hard-wired into our genes as an evolutionary trip-switch against hopelessness. Hope requires a courageous optimism and faith that as a species our existence as humans transcends even the darkest of times. It’s not wishy-washy stuff — we’d be extinct long ago if this wasn’t true.

After leaving the gallery, I wondered if I had mistakenly shaken anyone’s hands or hugged friends unthinkingly. Suspicion and paranoia set in. I washed up just to be sure. This is our new normal. A few days later, on March 15, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a national state of disaster after South Africa confirmed 62 cases of Covid-19.

Everything changed overnight.

Events cancelled. Travel bans. Panic-buying. University shutdowns. Workplace restructuring. Social distancing. Isolations. Quarantines. Economic meltdowns. Anxiety. Uncertainty. You name it; we’re going to experience it. We are living through extraordinary times. On March 5 our country’s first case of this novel coronavirus was confirmed in the small town of Hilton, a few kilometres from my hometown of Pietermaritzburg.

We can panic, or we can activate hope and empathy as central pivots around which we consider a human-centred approach to dealing with a biological pandemic. Handwashing is vital — but so is our short- and long-term mental health.

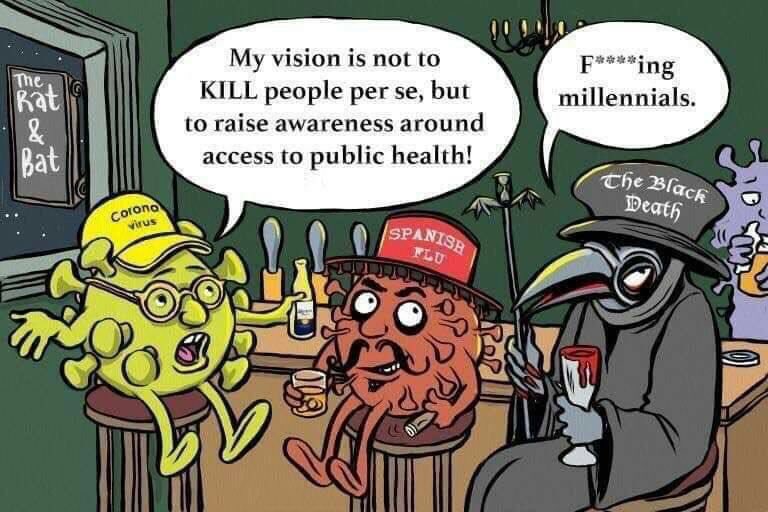

Scenes of the Italians singing from their balconies remind us to humanise our response to “staying safe”. It’s tricky. Social distancing is the very antithesis of how to promote good mental health. I smiled at the video of our Ndlovu Youth Choir educating us through song and dance. I giggle every day at the endless memes and jokes reminding us that humour and safety are not mutually exclusive. I laughed out loud at Carlos Amato’s cartoon of the coronavirus sitting in a bar telling everyone that Covid-19 is not trying to kill anyone, it just wants to create awareness about public health; to which The Black Death responds, “F***ing millennials”.

These are islands of hope.

But people are dying. And will die. Some people will die sooner than others because they already have compromised immune systems; or are excluded from the steady stream of online information. We know that life is going to get worse before it gets better. South Africa’s exorbitant inequalities and grotesque list of other public health issues — from violence to viruses — will not make this easy.

Our government is already being rightly critiqued for not acting with the same devoted urgency for other matters that — both numerically and emotionally — are as serious, such as hunger, suicide, and femicide. Globally, politicians have also been paradoxically lambasted for treating Covid-19 with the seriousness it deserves mostly because high-income countries remain the epicentre, and rich lives matter more than, say, the lives of West Africans during the Ebola outbreak in 2014 (in which the global response was nowhere near as dramatic).

The neoliberal politics of how/where/why governments respond is a troubling issue that reveals tensions in global public health. Some publics seem to matter more than others. Social distancing and regular hand-washing, for example, cannot be uncritically imported from the West into (South) African contexts that are densely populated and poverty-stricken, lacking basic access to secure housing, water and sanitation. Hope only works if there’s empathy for particular realities — and our solutions must match up to these varied settings.

Of course, no approach will be perfect. Part of our eventual return to normalcy — when it happens — will have to include frank confessions about what is and was normal to begin with, and how our responses to Covid-19 exposed deep fractures and difficult truths about who we value in society and what kinds of problems get immediate financial and moral attention.

Issuing self-quarantine instructions to those who test positive but are asymptomatic relies on the assumption that people understand our interconnectedness and respect our interdependence. We’ve always known this — climate change is a good example — but now this eternal truth is slapping us in the faces. “We’re in this together!” is the message — umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu, as the Zulu idiom goes, or motho ke motho ka batho, in Northern Sotho. A person is a person through other people; I am because you are. Ironically, despite the call for social distance, this pandemic might unite us in our collective purpose and civic duties.

What will photographs of 2020 look like in exhibitions of the future? Would humanity in a time of Covid-19 leave behind an archive of altruism or anarchy, of unity or division, of fatality or solidarity?

I am certain that while the politics of hope is not uncomplicated, we trust in the robust endurance of coming together as a society, being the tribal creatures that we are. It is essential to our own mental health and our collective wellbeing that we do so. Social distance isn’t emotional distance.

Suntosh R Pillay is a clinical psychologist in the public sector and writes independent social commentary