Siphiwo Mahala – author of Red Apple Dreams & Other Stories – with his grandmother, Shinana Thembani, whom he describes as ‘an exceptional storyteller‘. (Supplied)

I was partly raised by my grandmother, Shinana Thembani of the Madiba clan, who remains one of the most exceptional storytellers I have ever come across. Though she raised us in a village, we never sat around the fireside in the evenings to listen to stories, as is common in the cultures of other traditional communities. Her storytelling was spontaneous.

My most vivid memories involve my grandmother telling stories while sewing grass mats or cooking with her three-legged pot.

One of the most unforgettable narratives unfolded while she was preparing to wash a pillow. Perhaps I should explain how she made pillows: she would take an empty sack, fill it with old clothes, and stitch its mouth so that it became something that resembled a pillow.

When the “pillow” was extremely soiled, she would unstitch and empty it so that she could wash the sack. As she took the various pieces of cloth out of the sack, she would tell a story about each item: “This cloth is from the blouse I was wearing when your grandfather noticed me amongst all other girls. Do you know how beautiful I was at the time? I never used any skin lighteners because I come from a lineage of people with fair complexion…” A story that began with a cloth would develop into a narrative of family history.

My grandmother’s stories illustrated the entanglements of oral narratives and the modern (written) short story. Our role as children was to contribute by laughing, squirming, responding to her chants, and at times asking questions. Afterwards, we would retell the stories to one another, try to make sense of certain parts, reimagine others, create new characters, argue over the facts, the logic and the meaning. We were the audience, critics and storytellers at the same time.

Siphiwo Mahala’s most vivid memories are of her telling stories while sewing grass mats or cooking with her three-legged pot. (Delwyn Verasamy)

Siphiwo Mahala’s most vivid memories are of her telling stories while sewing grass mats or cooking with her three-legged pot. (Delwyn Verasamy)

In retrospect, these oral narratives were the foundation upon which my literary appreciation was built. From listening to my grandmother’s oral narratives, we went on to sit around the radio and listen to serialised stories. Once I could read and enjoy stories on my own, I immersed myself in isiXhosa literature. The short collections I particularly liked included Kwezo Mpindo ZeTsitsa by Archibald Campbell Jordan (1974) and Amathol’ Eendaba by PT Mtuze (1977), which I still revisit from time to time.

In his introduction to Hungry Flames and Other Black South African Short Stories (1986), Mbulelo Mzamane draws parallels between oral tradition and the written story: “The short story tradition in South Africa is as old as the isiXhosa intsomi; the isiZulu inganekwane; the Sesotho tsomo and other indigenous oral narrative forms.”

And in his introduction to The New Century of South African Short Stories (2004), Michael Chapman argues: “Many commentators have found a unity between ancient oral stories and modern written stories in that, to a greater degree than the novel, the short story invites the participation of its listener or reader. Its brevity and elusiveness challenge its audience to ‘complete’ its suggestion and to seek coherence, and even the experience, or the style, signals dislocation.”

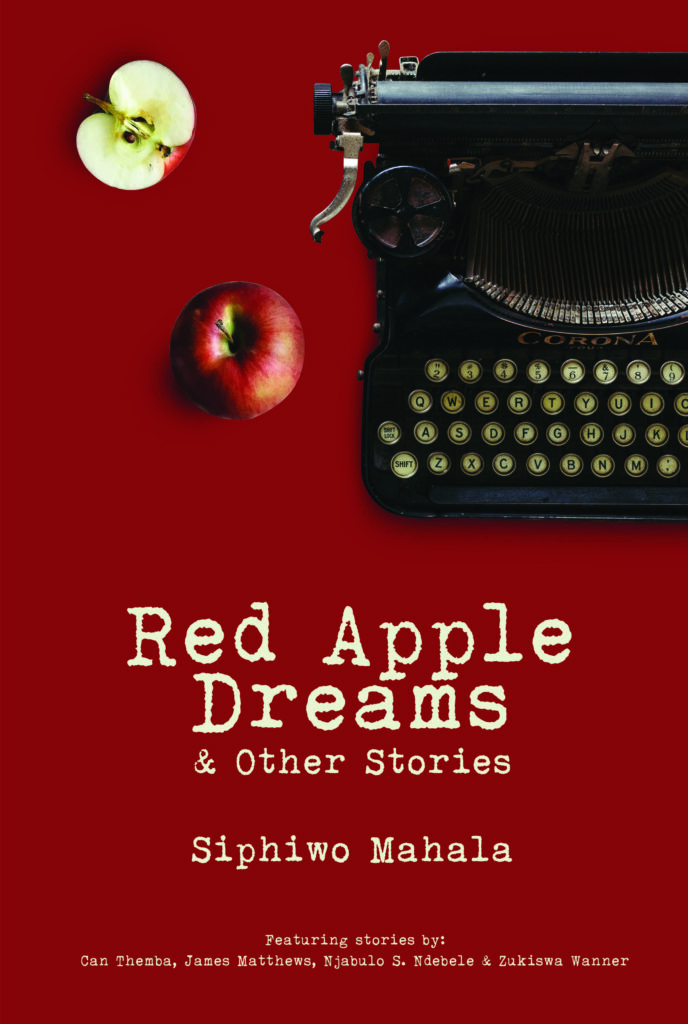

Red Apple Dreams & Other Stories by Siphiwo Mahala

Red Apple Dreams & Other Stories by Siphiwo MahalaThe written form of the short story in South Africa grew significantly in the early 20th century, with Herman Charles Bosman as its most revered exponent. It flourished, reaching unprecedented heights from the 1950s to early 1960s, when Drum magazine emerged as the major catalyst in the development of the genre. This was the period that Lewis Nkosi calls “the fabulous decade”, which saw the likes of Can Themba, Bloke Modisane, Casey Motsisi and others emerging as prominent scribes. Nadine Gordimer, though she started writing way before the establishment of Drum, was a major contributor during this period.

The short story in South Africa thrived thanks to regular publishing platforms such as Drum, Nat Nakasa’s The Classic, and Staffrider, which was prominent from the 1970s until the turn of the century.

In the early 2000s, the South African publishing industry was growing, with more black writers getting published by Kwela Books and Jacana Media, among others. In 2006, Mary Watson became the first South African author to win the Caine prize for African Writing, one of the most prestigious short story awards for African writers. She was soon followed by Henrietta Rose-Innes in 2008.

In that year, one of the finest but most underrated short-story writers in South Africa, Zachariah Rapola, won the coveted Noma award for African Publishing for his collection, Beginnings of a Dream. The award was sadly discontinued the very next year. Wordsetc and Baobab Literary Journal were established at the end of 2007 and beginning of 2008 respectively. Sadly, they were not long for this world.

From 2009, the effects of the global economic downturn hit publishing hard. The few houses that continued publishing short stories preferred anthologies, probably to appeal to wider markets. When I started looking for a publisher in 2010, many said on their websites that they did not publish short stories. This included Jacana Media, a major local publisher that did ultimately publish my short story collection African Delights in 2011. In the same year, Diane Awerbuck published Cabin Fever and Other Stories with Umuzi, an imprint of Random House.

NoViolet Bulawayo of Zimbabwe won the Caine prize for African writing in 2011 for her short story Hitting Budapest, which would also become the opening chapter of her award-winning novel We Need New Names, which itself was shortlisted for the 2013 Man Booker prize.

In 2012, the Commonwealth introduced a short story award for the best unpublished piece of fiction. By now it seemed clear the short story was coming back into favour. The watershed moment was when prominent Canadian short story writer Alice Munro was announced as the winner of the Nobel prize for literature in October 2013.

In South Africa, one of the newest emerging voices, Masande Ntshanga, won the PEN International New Voices award for his short story Space, which was also shortlisted for the Caine prize. The same year saw the return of struggle stalwart and seasoned novelist Achmat Dangor, with his collection Strange Pilgrimages. The middle of the decade saw a plethora of other notable authors publishing collections, including novelist Ivan Vladislavic’s 101 Detectives in 2015. In 2016, another young and dynamic South African writer, Lidudumalingani Mqombothi, was awarded the Caine prize.

Over the past three years, the most prolific writer has probably been Niq Mhlongo, who published two collections, Affluenza and Soweto (2016) and Under the Apricot Tree (2018). Most recently, Fred Khumalo published his first collection of short stories, Talk of the Town (2019).

The short story is probably enjoying its finest hour since the dawn of democracy in South Africa. The emergence of subgenres like flash fiction, the technological innovations that make it easy to read from portable devices, and the rising popularity of blogs and other online platforms all make the shorter narrative the most viable literary form — as well as the shrinking of time available both for writing and for reading.

It certainly remains my preferred form of writing.

There is no universal definition of a short story, but it is generally accepted that it is not a shorter version of a novel. It is a robust genre in its own right — more technically challenging than the novel, I find, obliging you to use fewer words in telling a complex narrative.

It can capture the essence of a narrative in the same way a novel does, and present dialogue as found in drama. It might wax as philosophically as an essay or as lyrically as a poem. The story becomes short principally because of the impeccable application of some of these elements, as well as its economy with words — though there is no clearly defined limit to its length.

One of the most prominent short story writers and foremost literary critics in South Africa, Njabulo S Ndebele, wrote a story that runs to more than 100 pages, but the eponymous Fools of Fools and Other Stories (1983) is nevertheless regarded as a short story.

Ndebele is the single greatest influence on my writing.

Through his stories, I could hear idiomatic African expressions, interact with familiar characters and visualise township settings I had never before encountered in English.

I would later encounter the works of Sindiwe Magona, whose writing felt like being allowed to eavesdrop on a conversation between my mother and her friends.

The works of other African writers, from Bessie Head, Ngugi wa Thiongó to Chinua Achebe, exposed me to different cultures, histories and linguistic nuances of societies across the continent.

I did my undergraduate studies at the University of Fort Hare, when Mbulelo Mzamane, one of the foremost critics and proponents of short story writing, was vice chancellor. He made it his mission to make available material by African and South African writers. The short story was his medium of choice; it became mine too.

Although I usually point to 2001 as the beginning of my journey as a writer, a former schoolmate recently reminded me that what I am doing now is the culmination of the drawings I used to do in primary school. I have clear recollections of writing and illustrating comic books that circulated around the school as far back as 1988.

This is the genesis of my apprenticeship as a storyteller, which has evolved through different forms over the years — from my grandmother’s spontaneous stories to drawings and published works of fiction.

Siphiwo Mahala’s Red Apple Dreams and Other Stories is published by Iconic Productions. This is an edited version of the essay that opens the book