Secessionist leader Isaac Adaka Boro, who in 1966 turned himself to the authorities. As the writer notes, the faces of Ologbosere and Boro, both destined to be executed, are tranquil, even foreknowing, as if the matter is settled. (Records Administration )

Consider these reverberations.

Sometime in mid-May 1899, the Benin warrior known as General Ologbosere was captured for leading a guerrilla war of resistance against British forces. Two years before, Ologbosere had masterminded an attack on a British expedition outside of Benin, killing at least 10 Europeans and 200 African carriers. Retribution was prompt, and an armed, so-called punitive expedition was organised.

Five weeks later, Benin was captured. The king was deposed and exiled, his empire annexed into the colonial administration. Ologbosere and four other chiefs maintained a resistance outside the city, hiding in and launching offensives from villages that supported the resistance. The British forces burned those villages, destroyed crops, detained young people and incarcerated rulers. Eventually, war-weary villagers betrayed Ologbosere and his cohorts. Less than two months after his arrest he was hung, with two others.

A day before his execution, contrary to the testimony of the chiefs, who decided that his life be forfeited according to native law, he contended that he was scapegoated. “The day I was selected to go to Benin City to meet the white men, all the chiefs were present in the meeting, and now they want to put the whole thing on my shoulders.”

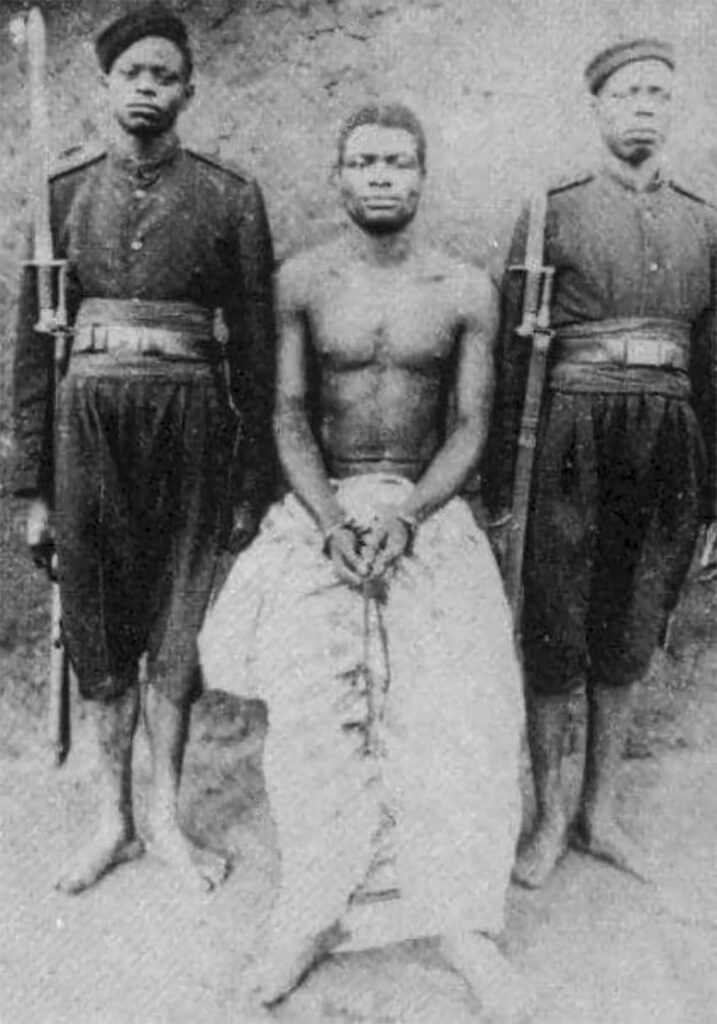

General Ologbosere before his execution in 1899. (Records Administration )

General Ologbosere before his execution in 1899. (Records Administration )

While Ologbosere awaits execution, a photograph is taken. He has been stripped to the waist and made to sit. He is handcuffed, flanked on either side by men of the colonial regiment.

A similar photograph, of Isaac Jasper Adaka Boro, was taken almost seven decades later. He is handcuffed, stripped to the waist, surrounded by men of the Nigerian army. In March 1966, Nigerian federal forces arrested Boro. For days he’d led men of the Niger Delta Volunteer Service in a secessionist attempt to form the Niger Delta People’s Republic.

Fourteen days earlier, he supervised a brisk swearing-in ceremony where he gave marching orders to his men, known as servicemen. At exactly 6.30pm they marched off, chanting victory songs. Better-armed government troops arrived the following day. After a week, it became foolhardy for Boro and his men to continue. Federal soldiers arrested relatives of servicemen, assaulted women and looted houses.

The revolution was called off. The secessionist fighters surrendered themselves in batches. Then Boro, their general commanding officer, turned himself in.

How were these prisoners seen in those moments of submission? What did they become in the hands of their captors? And, who made the photographs? Perhaps, for Ologbosere, a photographer attached to the consul general of the Niger Coast Protectorate. Or, for Adaka Boro, a press photographer embedded with the Nigerian army. Those details are secondary to the historical significance of the images. Once-feared, once-wanted men were displayed, subdued — emblems of the denouement of their stories.

Ologbosere’s photograph, in which he sits, is inarguably orchestrated — in 1899, you had to stay still to get a clear picture. Yet in that of Boro there is equally the possibility of orchestration. Like Ologbosere, he seems aware of a camera positioned to picture him. Whether they look towards the camera or away, their glances are steadied and their poses readied.

In all the time they battled the government, one can imagine that they accepted the risk of capture. Their faces are tranquil, even foreknowing, as if the matter is settled. Once triangulated — their lives as men who were disillusioned with the status quo, and who took to extreme measures to fight for their convictions — the photographs elicit propositions hard to ignore.

A body stripped to the waist. Is that the ideal subordinated body?

These are bodies in public; bodies in the national glare.

One photograph is of a man adjudged guilty in 1971, trussed up, ready for execution and yet showing no sign of remorse. On Thursday, September 9 1971, the morning after Ishola Oyenusi’s death, his photograph was published on the front page of a national newspaper with the headline: “Oyenusi smiles to his death.” Below the photograph is a smaller-sized caption: “Trussed up but still smiling. Oyenusi at the stake yesterday.” The execution took place on a Lagos beach, with an audience estimated at 30 000.

At the outset, the Daily Times reporters describe a paradox. Here’s a man destined to die pictured smiling: “Tears and jeers followed the execution of the master armed robber, Ishola Oyenusi, and his comrades in crime at the Lagos Bar Beach yesterday. The tears flowed from a few friends and relations and those who could not stand the sight of blood. The vast majority of viewers, however, booed in derision, apparently content that a major victory had been won for peace, law and order. But the principal actor in yesterday’s Bar Beach show, notorious ‘doctor’ Ishola Oyenusi kept smiling — even on to his death.”

The highest point of a condemned man’s life — his execution — points backwards, to the activities that damned him. Oyenusi and six other men were condemned for robbing a factory in Ikeja, Lagos of £28 000, killing a police constable in the process. Of his first robbery, legend says he snatched a car for his stranded girlfriend — “he was quite gentlemanly and chivalrous” — killing the owner in the process. And he was arrogant: in 1970 he shot a policeman who attempted to arrest him, and said, “People like you don’t talk to me like that when I am armed. I gun them down.”

To the crowd that “booed in derision, apparently content that a major victory had been won for peace, law and order”, he offers a smile, as if to deride their derision. A double negative: the smile of a condemned man cancels the derisive boos of the crowd at his execution. How could he have looked on death so remarkably unfazed?

His final appearance is incommensurate with expectation. For an onlooker today, he has not become the “good thief”, contrite in the face of death; the thief who asks to be remembered in heaven. I encounter an inconsistency in matching the horror of his deeds with the ludicrousness of his smiling face. Two unparalleled desires coincide: the desire to mete out justice on a notorious armed robber and his gang, and the desire of the notorious armed robber to exit the stage with elation, spectacle and fulfilment.

What is the promise of a paradoxical photograph? Which man smiles on his execution day? Not the smile of a martyr, who glimpses paradise. I am only barely informed of those who mourned him — “The tears flowed from a few friends and relations and those who could not stand the sight of blood.” His narrative is entirely framed within the milieu of crime. There is no respect he deserves, I am told, no humanity except punishment, no qualifying word but “notorious” and, therefore, no counternarrative.

A 2015 recounting of his notoriety by the Nigerian website Pulse.ng — “Profiling Nigeria’s Notorious Armed Robbers: (‘Doctor’ Ishola Oyenusi)” — explains his smile as follows: “Before he was executed on Wednesday, September 8 1971, at the famous Bar Beach show in front of 30 000 watching Nigerians, no one believed that ‘The Doctor’ would be captured, as he was famed for ‘disappearing’, [or that] his body was capable of being pierced by bullets. In fact, he must have had so much faith in his charms that he smiled all the way to the stake and even as soldiers aimed their rifles at him and his co-criminals, Oyenusi still radiated an aura of invincibility.”

What this suggests, in its sure-footed rhetoric, is also a sentiment riddled with clichés. We are uncertain of what to make of a society where a man as feared as Oyenusi thrives. We exaggerate his monstrosities, ennoble him with an “aura of invincibility” and mystify his power over us. Think about the long list of Nigerian criminals characterised as possessing charms. Think about the assortment of diabolical items on display when robbers are paraded shirtless by the police.

Considered in this light, Oyenusi’s smile is a taunt. Like Adolf Eichmann in a Jerusalem court, his smile is declarative: “I am not the monster I am made out to be. I am a little leaf in the whirlwind of history.” If you push these declarations to their farthest limit, you encounter the same vicious paradox.

Trussed up, but still smiling.

Even Oyenusi, at the final moment, consoled himself with clichés. In that Daily Times report, he is said to have screamed, “I am dying for the offence I have committed!” Whether he believed this is not relevant to anyone but him, for sometimes we peddle clichés to arrive at unwavering convictions. For those people who outlived him, whose attention is repeatedly drawn to his contrariety, the most promising entry to his story is what’s uncertain, likely unknowable, about his demeanour.

Let us speculate for a moment on the sort of viewers gratified by the shooting of condemned men. Oyenusi’s execution was preceded, months earlier, by other firing squads. On August 24 1970, three men, former Biafran soldiers, were publicly executed for armed robbery. On March 25 1971, two armed robbers were also publicly executed.

Videos from the Associated Press archives document the executions. The men are dragged, hooded, tied, prayed for; martial music is played to the marching strides of army officers. The sentence is read, then a line of kneeling soldiers intermittently open fire. Earlier, the camera’s panning movement captures the surrounding crowd. There are those who climb on trucks to see better, who crouch in front, who stand behind. People clamber to find vantage spots. As soon as rifles are trained at the villains, there is anticipatory silence.

Oyenusi’s smile cannot escape the public he faces, to whom it is likely addressed. Our relationship with the paradox his photograph presents is bound with our interest in violent public justice.

An execution is public if it invites viewers to watch justice unfold. In this sense, the viewers are allied with the executioner — chastising the executed, surviving him. The prevailing proposition is that, on the death of a dangerous armed robber, the world is less dangerous. Yet it is possible to think of a larger climate of fear that survives the feared.

When we look back at Nigeria in the early 1970s, barely emerging from the chaos of a war, led by a military government, we consider a milieu in which a violent response to crime and dissidence was consensual. Oyenusi’s execution is the synecdochical flashpoint of that milieu.

A public display of justice does not necessarily resolve a larger climate of fear. We understand that a crime is committed against the community whose law is violated, not merely the individual victim. We also permit the state’s use of violence to ensure that the framework of its existence — law and order — is not threatened. But here’s a dilemma: How do we separate such acts of state as capital punishment from the bureaucracy that makes it impossible and unachievable to ensure the safety of “innocent” Nigerian lives?

That many of us stand adjudged and disposable — “suffering and smiling”, looking and laughing, matching misery with mirth — is one lesson from Oyenusi’s demeanour. If this comparison seems defective, I ask you to return to the banality of Oyenusi’s execution, right there on his smiling face.

Dying as theatre. Everyone has, for the fraction of a moment, considered the instant of death. To die surrounded by those we love, on a bed. To die watched by those who consider us enemies, on a stake. To die by accident, our bodies trammelled by crushed metal. However impertinent some of these possibilities are, dying presents itself as a performance. We have been cast as principal actors.

How may Oyenusi’s photograph portray an armed robber, even as it pivots into an emblem of national history?

Another photograph is of a Mercedes-Benz, its windshield pockmarked by bullets. Most Nigerians of my generation who visited the Nigerian National Museum in Lagos as children would have seen it on display, parked in a gallery. This is the car General Murtala Mohammed died in on February 13 1976. He had been head of state for a mere eight months, killed in an abortive coup led by Lieutenant Colonel Bukar Dimka.

Oyenusi’s execution — as synecdoche, as the flashpoint of a milieu of public display of justice — foreshadows the death of General Murtala Mohammed. In a strict sense ,there is nothing similar about their deaths: one is remembered as a villain; the other as a hero.

Perhaps no other military head of state is memorialised as Murtala Mohammed has been — an international airport is named after him, his image is on the ubiquitous 20 naira note and his official car was displayed in the Nigerian National Museum, a kind of perpetual lament. Yet, in a liberal sense, Dimka’s miscalculated attack is one additional subplot in the story of justice as spectacle.

Those who died in Nigeria’s coups d’état were executed because revolutionary junior officers or factional senior officers considered their rule a crime. The penalty for proximity to power was death. The coup plotters knew that, in most cases, death was the only way to subvert the invincibility of the ruling class, to usurp its legitimacy; that if they had gained a hold on the government through force, or in the absence of consensus, they would lose that hold in a similar manner.

This is why in the first hour or two of a coup, the plotters, of necessity, take to national radio. They read a prepared statement that announces their legitimacy and suspends the constitution. They suggest they have taken to extreme measures for the good of the nation. Their proclamations are, at best, farcical. It is no more ironic than a government who supposes public executions of armed robbers would keep the country safe. Either action belies a foundational assumption: power is guaranteed and perpetuated by publicity.

All the photographs invoked above consolidate in a final image, in which the bluster of power is most evident. If the triangulation of photos of Ologbosere and Boro reveals the status of the treasonous body, and if the pairing of Oyenusi and Mohammed suggests the workings of justice as spectacle, this one is a vainglorious asset of the political class in the 1970s, who might have sought to emerge from that decade unscathed.

In 1977, after General Olusegun Obasanjo had proclaimed, “The star of our peoples is on the ascendancy”, and after tens of thousands of people had assembled at the National Stadium in Lagos for the opening ceremony of Festac in January that year, the Nigerian head of state is pictured with the American president in the White House. It’s a photograph of utter, feel-good gravitas.

Then presidents Jimmy Carter (America) and Olusegun Obasanjo (Nigeria) in October 1977. (Nara and Carter White House Photographs Collection/National Archives)

Then presidents Jimmy Carter (America) and Olusegun Obasanjo (Nigeria) in October 1977. (Nara and Carter White House Photographs Collection/National Archives)

The American wears a suit and tie; the Nigerian matching ashoke. They are framed by the spare grandeur of a room in the White House — its candelabras, deep-blue ornate rug and gold-plated chairs. But look closely and see that the photograph depicts the host a step behind his guest, almost as though relegated or inferior, looking less composed.

This is a photograph of Obasanjo on October 11 1977, still revelling in the cultural spectacle he commandeered earlier in the year. He clasps his hands around the head of a swagger stick and glances at the camera, as if with a taunt. His gravitas is sponsored by petrodollars. He is outfitted to mark a season of promise, uniformed to tout political equality. But his appearance became symbolic of a hope deferred, like a lineage of men outbalanced on the measuring scale of power, whether they were villains or heroes.

This piece initially appeared in Festac ’77, a book published by Chimurenga. To purchase the book please visit here