Bodybuilding theme party at Frágil, Lisbon, 1983. (José Soares e Nica)

Never did Lisbon’s social landscape change as quickly as in the first decade of the 2000s. It was an opportunity to create new languages, imaginary worlds, and other kinds of experiences. It was becoming clear that the city was increasingly inhabited by people of different colours, roots and experiences.

Still, the majority of those people were, and are, looked down upon by most of Portuguese society as immigrants. But most of them are not immigrants. They’re just Portuguese – with skin tones, family stories, and customs that are different from the romantic image that Portugal still has of itself.

Indeed, this change began with the immigration from Portuguese-speaking African countries, followed by Brazil and Eastern Europe. Slowly, the traditional Lisbon of fado, popular festivities, marches and roasted sardines, based on idealised concepts of what tradition was supposed to be, was merging with other realities. In recent years, several creative agents who work in different artistic practices, especially music, have reflected on this development.

The strongest example for this would be Buraka Som Sistema. But there are other examples, such as Batida DJ Marfox, DJ Nigga Fox, Macacos Do Chinês, Kilu, or Ritchaz & Kéke. All produced new Portuguese music that came from the descendants of second-generation immigrants. They are all different, from different generations, origins, cultural capitals and motivations. They do not want to be a symbol for anything.

None of them want their art to be trapped within their identity. But they unwittingly reflect a city from southern Europe, Lisbon, with the Atlantic Ocean by its side, and its privileged connections to Brazil, parts of Africa, and the rest of Europe, knowing that they can filter that vast legacy. Especially because recent years have shown that Lisbon’s language is already made of Portuguese and Creole, of fado and kuduro, of clubs such as Lux but also B.Leza, black and white people and mixed races.

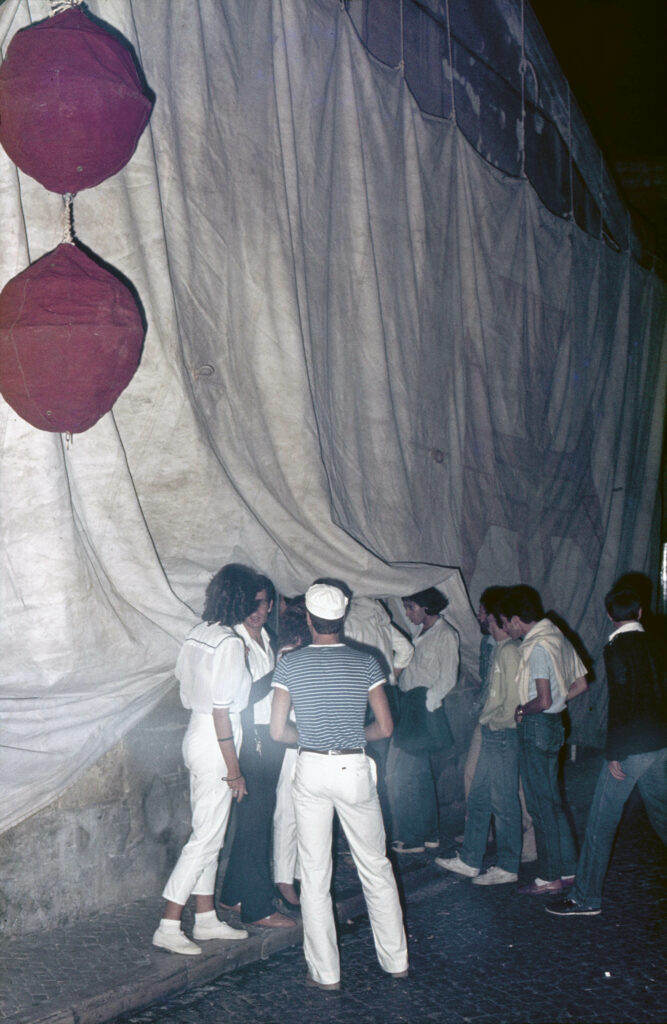

Entrance of Frágil, sailor party, Lisbon, 1983. (José Soares e Nica)

Entrance of Frágil, sailor party, Lisbon, 1983. (José Soares e Nica)

Lisbon is a hybrid and diverse city in the making. When walking around historic neighbourhoods like Bairro Alto, Chiado, Santos, Bica, Mouraria, Intendente, or Cais do Sodré, that reality is present. Observers often do not realise it is there. Because they try to legitimise differences, people often use expressions like “Lusophone”, “second-generation immigrants”, or “Luso-Africans” – not realising that they are actually establishing separations, and divisions.

But new Lisboners’ range of references is wider. They bring new elements, promote diversity, and use different languages, like hip-hop, popular Portuguese music, kizomba, or kuduro, in a non-hierarchical way. They do not reject anything, whether it is their parents’ culture or global culture. They are not easy to categorise because most of them want to understand and assimilate everything that is around them.

If one band embodies all of Portugal’s transformations in the last few years, that band would have to be Buraka Som Sistema and their completely untameable, plural, and under-construction sound. Instead of separating, they have always preferred to agglutinate things. When they appeared, they met an increasingly receptive international environment that started to accept urban languages like Brazilian baile funk or South African kwaito. Buraka Som Sistema came from the creative cauldron of Enchufada, a studio, record label, and creative unit that also gave birth to bands like 1-UIK Project. They were composed of two Portuguese (João Barbosa and Rui Pité) and two Angolans (Kalaf Ângelo and Andro Carvalho, ex-Conjunto Ngonguenha) who had been living in Portugal for a long time.

Buraka Som Sistema started their career with their 2006 sessions in Clube Mercado. There, with no previous releases, people started to talk about them, which immediately established them as a project from Lisbon. The band would have been different had it been born in Luanda, São Paulo, or in any other part of the world. But the two Portuguese members’ backgrounds, whether from rock or house, met with the Angolans’ knowledge of African music. All this only made sense in Lisbon.

In the international press, Buraka Som Sistema were sometimes referred to as “Angolan” or “African”. Maybe this attribution appeared because there was still some difficulty – inside and outside of Portugal – to understand the changes of a country now inhabited by people of different colours, origins, and experiences. But now the change is there. With new generations and a wide array of references. With parents who have inherited traditional African cultural forms, but who also have been socialised in Portugal, and who are aware that they are living in a global culture and belong to a transnational space. No other contemporary music reflects Portugal and especially Lisbon – the streets’ reality instead of their own romanticised image – as much as the one from Buraka Som Sistema.

The band’s success did not come easily. They moved in a territory of ambivalent identities, despite having become the most internationally recognised Portuguese act of all time, outside of the fado circuit. Still, its musical perspirations could not defy all stereotypes. They were challenging the view of Portuguese people. In 2016 the band took a hiatus from performing. It might still be too soon to understand the real impact that they had on cosmopolitan and post-colonial Portugal.

But things have already changed. A current example for this would be the monthly Príncipe record label nights in MusicBox, in the Cais do Sodré area. For this label and platform youngsters from Lisbon’s periphery are currently making, with their own hands, some of the most exciting new Portuguese music of today. They produce this electronic dance music in their bedrooms or living rooms, later to be danced to at parties where people of different colours, ages, clothing styles, and levels of wealth gather. It is all based on this music. Music that can be kuduro, Afro-house, funaná, or tarraxinha – or all of it at the same time.

On these nights at the MusicBox, “periphery” and “centre” come together without remission in sweaty, festive nights. MusicBox is perhaps the most symptomatic case of how some bohemian and cultural places have been diversifying in the last decade. With the increasing popularisation of Bairro Alto other neighbourhoods such as Bica, Cais do Sodré, and, more recently, Intendente have become more central.

Margarida Martins and Mário Marques, Absolut Citron Party, Frágil, Lisbon. (unknown)

Margarida Martins and Mário Marques, Absolut Citron Party, Frágil, Lisbon. (unknown)

Cultural neighbourhoods

Cultural neighbourhoods exist in many cities. Their model changes, but usually they are areas that have been reconverted into creative and informal environments, offering a mixture of cafés, bars, art galleries, clubs and live music venues. Here, emerging artists can experiment. Sometimes these neighbourhoods’ borders are undetermined. But inside, one feels one has entered a cultural community and may interact with it. In Lisbon, there have been two such areas since the 1980s, according to sociologist Pedro Costa: Bairro Alto and neighbouring Chiado. Both complement each other, as autonomous systems. Bairro Alto represents a more nocturnal side, linked to transgression and emergent activities. Chiado, where one can find the largest concentration of bookstores in the country, stands for the daytime.

The Bairro Alto-Chiado axis is one of the city’s most important centres for nightlife, performing arts, fashion, antique stores, literature, audio-visual production and visual arts. It is known for its many cultural activities, and especially for the development of a creative field that favours information exchange and the spreading of innovation, and for how tolerant and warmly even the most alternative cultural presentations are welcomed. This is a centre that works as a basis for a production system of cultural activities. But it also has a specific self-governing system and its own system of representations.

In Bairro Alto, in the 2000s, places that were former landmarks of the 1980s and 1990s, like Frágil or Captain Kirk, have lost their iconic value. There are still some places that stand out, for example bars like Maria Caxuxa, Clube da Esquina, or Purex, dancing bars like Bedroom, 49, or art galleries such as ZDB. But nowadays most things happen outdoors, on the streets and crossroads and squares. Until now, there has been a sort of self-adjustment process in the neighbourhood. However, excesses, from venues as well as from their punters, may lead to its collapse, after which the area might regenerate itself once again.

Ten Cities (Spector Books/Goethe-Institut), a book on clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Naples, Berlin, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol and Lisbon between 1960 and March 2020, is edited by Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo and Florian Sievers. This extract, on the creative cauldron of club culture in Lisbon, is the tenth and last in a series of ten excerpts from the book